‘House of Lev’: A former hip hop dancer and makeup artist document their new Orthodox life online

Akiva and Chava Hart and their 6 children converted to Judaism Nov. 5, but have been creating Jewish content online for a year

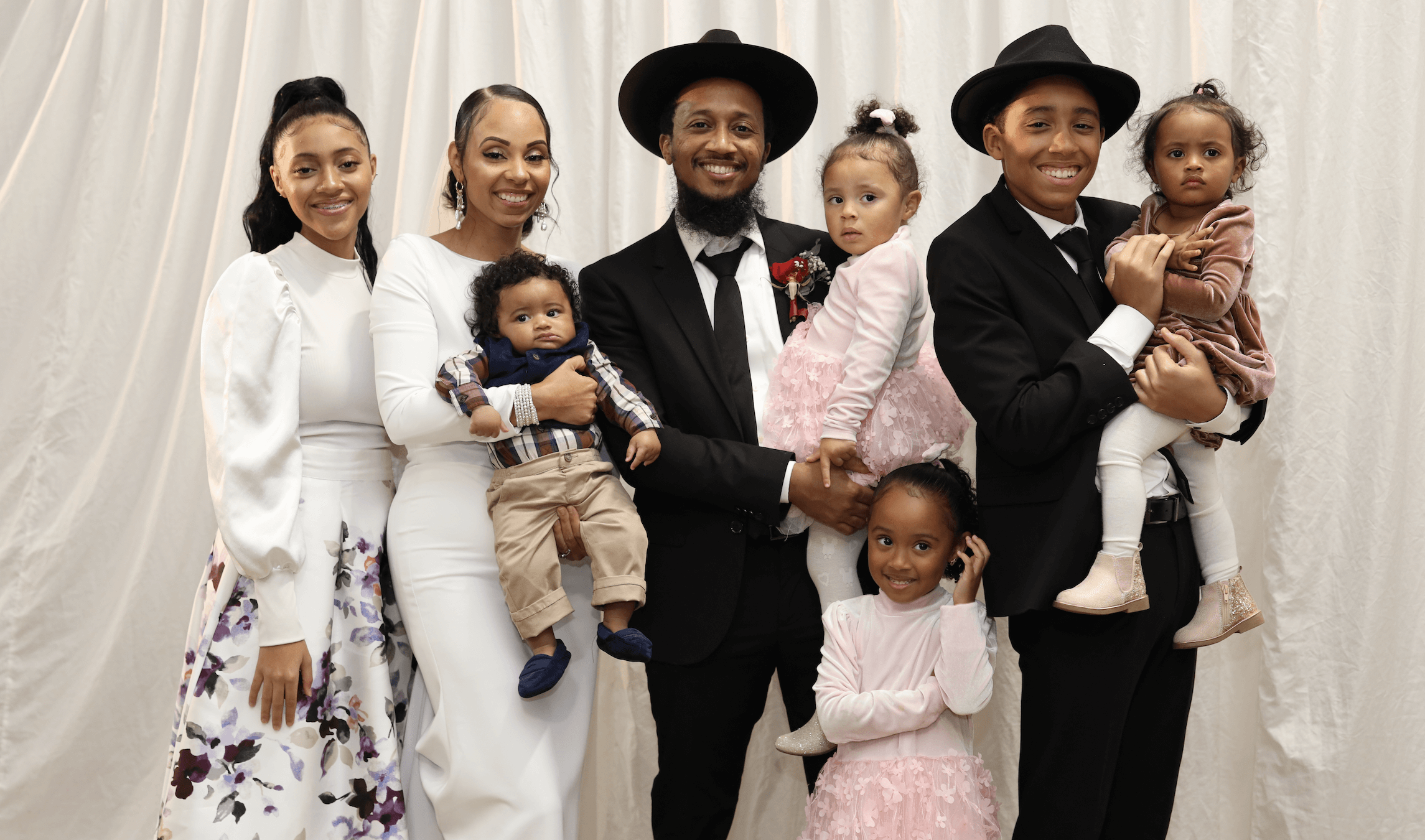

Akiva and Chava Hart and their six children converted to Judaism on Nov. 5, 2023. Then the married couple got married again in a Jewish ceremony. Photo by Levi Lehman

When LaDerryl Hart went to Israel as a dancer touring with rapper Missy Elliot, he had no inkling that 13 years later he would become an Orthodox Jew and take the name Akiva Nachman. Or that with his wife, who changed her name from Danielle to Chava Emunah, he would create the “House of Lev,” a multi-platform online presence detailing the story of their family’s conversion to Judaism.

On social media and their website, the Harts also offer insights into Jewish practice and sell House of Lev merchandise, from sweatshirts to tote bags. Their YouTube channel has 9,000 subscribers. Their Instagram account has nearly 30,000 followers. They also post Jewish content to TikTok and Twitter, where a recent video decrying antisemitism garnered 2,400 views. The couple has been Jewish for less than a month.

This quote about antisemitism hits the nail on the head. @HouseofLev

— Aish (@AishJewish) April 4, 2023

(From Professor Michael Curtis of Rutgers University) pic.twitter.com/2BMRlq4uqw

Weeks before they became Jewish, Hamas attacked Israel, murdering 1,200 and taking more than 230 captive, prompting a war that has brought hundreds of thousands to protest the Jewish state around the world. The horror in Israel only cemented their desire to convert, Avika and Chava said.

“We are running faster than ever now, running to join our people,” Akiva said on a video entitled, “We are standing with Israel,” that he and Chava posted to YouTube.

The Harts (“heart” in Hebrew is “lev”) and their six children — ages 6 months to 15 — converted on Nov. 5 after immersing in a mikvah near their Southern California congregation. It was the final step on a five-year journey toward Judaism, the last two spent in conversion classes and living observant lives.

Akiva, 39, and their eldest son, 14-year-old Betzalel, had a ceremonial drawing of a drop of blood to represent brit milah, the circumcision ritual, a week earlier. And on the day they converted, Akiva and Chava, joined in marriage for nearly 16 years, also celebrated their Jewish wedding at their synagogue, the Orthodox Beth Jacob Congregation of Irvine, surrounded by their new community.

Going to shul every morning to pray in a minyan, keeping strictly kosher and adhering to all the laws that come with being a fully observant Jew is a long way from dancing backup for Stevie Wonder at the 2005 Super Bowl halftime show. You can also see Akiva dance in a Gnarls Barkley-Cee Lo Green music video with Justin Timberlake. He says he traveled to 150 countries during his dance career.

Akiva Hart, then LaDerryl Hart, is the dancer wearing and orange shirt and pants.

But for Akiva and Chava, what they’ve given up feels insignificant compared with the lives they now lead.

“The structure in Judaism made a lot of sense to us,” said Chava, 38, who describes herself as a stay-at-home mom and a content creator. She previously worked as a makeup artist for television and film in Hollywood, including gigs with the BET network and an ad campaign for Cover Girl.

Neither she or Akiva has entirely given up on their earlier careers, parts of which they know are incompatible with Orthodox Jewish observance, which requires modesty in dress and a day of rest on Shabbat as well as many holidays on which they may not work.

But Chava said she plans to create shades of makeup for Jews of color which comply with Jewish laws prohibiting blending and smearing on Shabbat. Akiva said he plans to write and perform music for Jewish audiences. After their children are asleep, they record their videos in a studio in their garage.

An Orthodox life — on and offline

Their days are long; Akiva is up by 5:30 each morning to get to synagogue for morning minyan, followed by a Talmud class and then, an hour alone, talking to God. It’s a practice called hitbodedut, first written about by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, after whom Akiva adopted his new middle name.

“To be able to carve out an hour a day to spend with Hashem, I get a chance to pour out my heart. I talk to God like he’s in front of me, my best friend,” said Akiva. “Sometimes I laugh, sometimes I cry, I connect and it’s just me and God.”

Chava is up just as early, getting the three eldest children off to school — an Orthodox day school and soon a Jewish preschool for their 3-year-old — and taking care of the youngest ones at home.

The Breslov philosophy has influenced the deeply spiritual couple, who put out their first video about their journey toward Judaism a year ago. They have since posted dozens of others in which they document their Jewish firsts — wrapping tefillin, saying the blessing after meals, Akiva and Betzalel’s counting in their Orthodox minyan.

They also offer their own takes on Jewish experience, from marriage to their children’s handling of the conversion process (which mostly went very well, they said).

Their teenagers — 14-year-old Betzalel and 15-year-old Leah — came to Judaism on their own as they watched their parents explore and begin to observe Jewish law, Chava said. Had Betzalel and Leah not been on board, Rabbi Yisroel Ciner, the family’s sponsoring rabbi, said he would not have agreed to the conversion of Akiva and Chava. “Conversion is not meant to divide families,” said Ciner.

Some people, in comments to the Hart’s posts, have questioned the couple for documenting their Jewish journey on social media, accusing them of seeking fame and money. Akiva said he generally deletes negative comments and blocks those users.

While they are now primarily supported by Akiva’s job at a video production company that specializes in real estate, the couple also derive income from selling branded T-shirts and sweatshirts on their website, and from sponsorships with Jewish companies that make the head wraps and skirts Chava now wears, and the tallit and tefillin bags that Akiva and Betzalel use, among other items. They also get paid for speaking engagements at Chabads and other synagogues.

Ciner said the Harts social media presence “did not give me pause.”

They were well into the conversion process “before the whole social media thing exploded,” the rabbi said, noting that they had already moved from Los Angeles to Irvine to be close to the synagogue and put their kids into Jewish school. “It was clear that social media was not driving their process in any way.”

Akiva said he and Chava built the House of Lev cautiously and sought rabbinic approbation. “We didn’t want to do content if it would put a halt on our conversion process,” Akiva said. Ciner, he added, told them their social media was helping others to find Judaism, as did the three-rabbi court that approved their conversion.

Discovering Judaism

Both Harts grew up in Michigan. Akiva in a Detroit neighborhood he calls “the hood.” His family is close-knit and churchgoing, and some of his relatives still live on the street he grew up on. Chava was raised in Rochester, about a 45-minute drive north of Detroit, in a family that did not go to church, though she described her mother as “a lapsed Catholic” who prayed privately. At one point, her mother married — but then divorced — a Jewish man.

The couple met in 2006 outside a Detroit dance club and married the next year in a Christian ceremony, and regularly attended a nondenominational church. After several years they moved to the Los Angeles area to work in entertainment — Akiva as a dancer and choreographer, and Chava as a makeup artist.

The couple’s journey toward Judaism began five years ago, when one of Akiva’s cousins told him that he believes African Americans are “the real children of Israel.”

Akiva says he didn’t buy it, but the remark “sent me down a rabbit hole online.” He first saw videos from a group of Hebrew Israelites whose teachings he found “militant, antisemitic and very aggressive.” (The term “Hebrew Israelites” refers to a wide spectrum of groups, many of which eschew such teachings.) But much of what Akiva saw “turned me off because it was racist,” he said.

Then he came across videos and interviews with Nissim Black, the Orthodox rapper and Black convert to Judaism, finding his approach to Judaism inviting.

They wanted to find other Black Jews, but that proved challenging at first.

“I wanted to know that there are other Jews who look like us. We’d never seen any Jews of color,” said Akiva. Then, through Instagram, he met Yehudah Pryce, a social worker and a formerly incarcerated Black man who converted to Judaism. Pryce connected the Harts to a California Jewish community where they found themselves comfortable and eventually joined. Beth Jacob is more diverse than most, said both Akiva and Ciner, and includes Jews who are Black, Latinx and Asian.

Asked if they had encountered racism among Jews, or antisemitism in their Jewish journey, Akiva said only in online comments posted to their YouTube and Instagram pages. They have been warmly welcomed by their Jewish community, both he and Chava said.

“The thing that surprised us the most is how wonderful and beautiful the majority of Jewish community is compared to what you see in the media,” said Akiva, who said he used to work delivering food and thought that people in Jewish neighborhoods were giving him funny looks. He had once thought of Jews as controlling. “I got that from the way the media portrays Jewish people,” he said.

“Now we’ll see black hat Jews and realize that they’re just focused. Not angry,” said Chava. “The Jewish people are the most loving, kindest, giving people. That did surprise us.”

Now she is teaching head-wrapping techniques to observant Jewish women and as a pair, the Harts are raising money for Israel Defense Forces and speaking out in support of Israel, as on their latest sponsored video with a menorah manufacturer. Just in time for the family’s first Hanukkah as Jews.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO