Special ReportSpecial report: What’s it really like to be Jewish on campus right now?

We sent 11 reporters to colleges across the country to find out

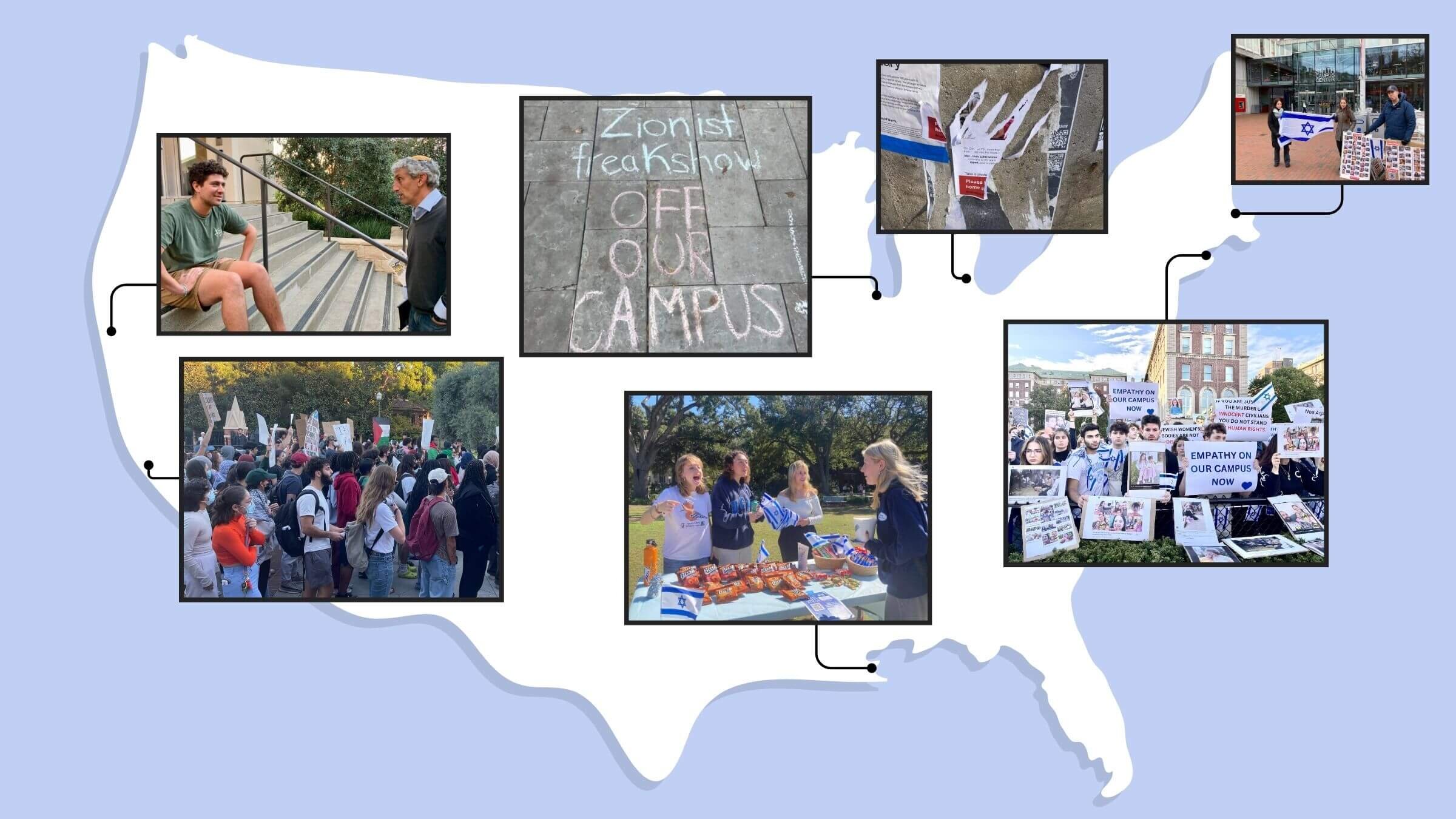

Four weeks into the Israel-Hamas war, a separate pernicious conflict is roiling American college campuses. Photos, clockwise from upper left, at U.C. Berkeley (by Kimberly Winston); U. Chicago (Debra Nussbaum Cohen); U. Michigan (Debrah Miszak); Harvard (Mira Fox); Columbia (Camillo Barone); Tulane (Leah Jablo); and USC (Louis Keene). Graphic by Matthew Litman

At the University of Chicago, a Jewish senior has stopped crossing the quad to get to her classes, going the long way around to avoid seeing slogans like “Zionist Freakshow Off Our Campus” and “Gaza is a Concentration Camp.”

The student head of Hillel at the University of Michigan, meanwhile, has been so consumed with the fallout from the Israel-Hamas war that she has had to ask for extensions on assignments — in some cases from faculty members who signed a letter condemning the school’s president for ignoring the plight of Palestinians after the Oct. 7 terror attack.

And at Rutgers University in New Jersey, the Israeli-American leader of a group called Peace is Possible is newly alienated from his Palestinian co-president.

The war “has made us argue in a way we hadn’t before,” said Or Doni, 20, a biology and neuroscience major. “He sent me a very long message a few days ago, talking about how he’s upset about things I’ve said, and how I’ve said them.”

Four weeks into the Israel-Hamas war, it’s clear there is a separate virulent and pernicious conflict roiling American college campuses that is not only terrorizing both Jewish and Muslim students but also testing the boundaries of free speech and the resilience of the academy.

The Anti Defamation League and Chabad on Campus report surges in antisemitic activity at institutions across the country. Jewish donors have threatened to abandon their alma maters over it and employers are blacklisting student activists because of it. Harvard, Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania have all appointed new groups to tackle it. Cornell took the extraordinary step of canceling classes Friday after an engineering student was arrested for threatening to kill Jews in posts to a campus message board.

We sent 11 reporters to campuses across the country last week to try and get beyond the heated headlines, to develop a deeper understanding of what Jewish students are experiencing at this tumultuous time. What emerged is a portrait of unease and anxiety, of a shifting landscape in which many of the nation’s brightest young people find themselves lonely, confused and concerned about what is unfolding around them.

Some are responding by taking off their yarmulkes or hiding their Stars of David in their shirts, while others are reaching for Jewish symbols and activities for the first time — at the University of Southern California, the Chabad rabbi said the number of students wanting to lay tefillin has quintupled from 25 to 125 per week.

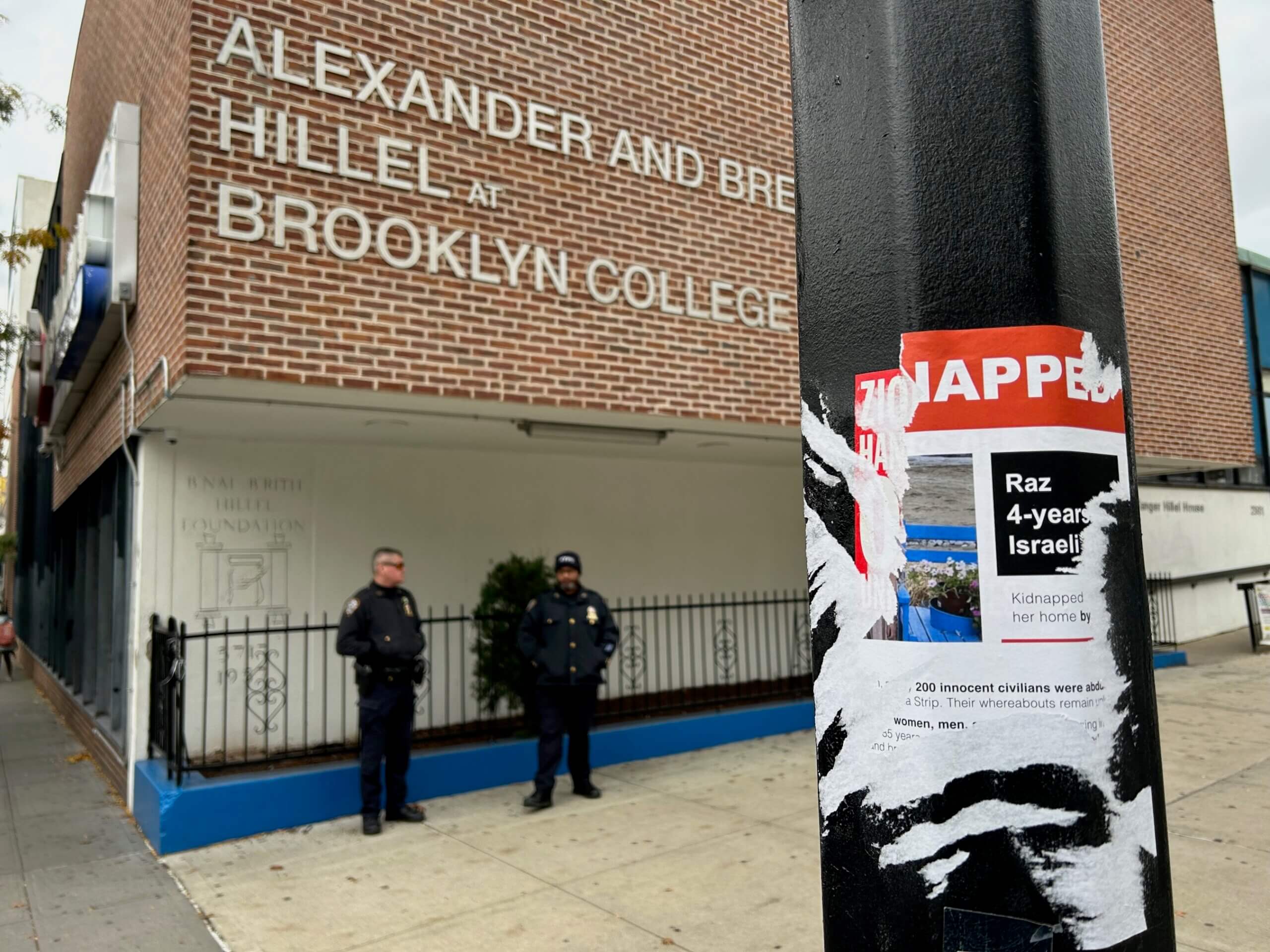

Several campuses we visited have added security around Hillel buildings or classes on Zionism — at Brooklyn College, a Jewish student from Virginia brought two New York Police Department officers hot cocoa and black-and-white cookies the other day to thank them.

And many students said they are just trying to muddle through midterms.

Sari Rosenberg, U. Michigan’s Hillel chair, said she struggled with whether to press ahead with the group’s annual semi-formal, called the Nice Jewish Ball, despite the war. Some skipped the event because it felt wrong during wartime, or because they’d fallen behind on schoolwork, she said, but those who were there treasured the tidbit of normalcy.

“I think people are looking for Jewish joy, and it felt really wholesome,” she said. “I got follow-up texts saying, ‘That’s exactly what I needed, to be dancing.’”

Below are dispatches from our visits to 11 American campuses last week.

Harvard University by Mira Fox

George Washington University by Arno Rosenfeld

Tulane University by Leah Jablo

University of Southern California by Louis Keene

Rutgers University by Adam Janos

Columbia University by Camillo Barone

University of Michigan by Debrah Miszak

Brooklyn College by Sam Lin-Sommer

University of California at Berkeley by Kimberly Winston

University of Chicago by Debra Nussbaum Cohen

Cornell University by Odeya Rosenband

Editing by Adam Langer, Lauren Markoe, Jodi Rudoren and Talya Zax.

Harvard: ‘Better for my mental health to be in a war zone’

By Mira Fox

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Shabbos Kestenbaum is the only Orthodox Jew at Harvard Divinity School, a famously left-wing outpost within a university that has been a focal point of pro-Palestinian activism — and related backlash — since the Oct. 7 attack. He considers himself a leftist: He voted for Sen. Bernie Sanders in the Democratic presidential primaries in 2016 and 2020, organized events in support of the Uyghurs in China, and is concerned about the civilian death toll in Gaza.

But he is anguished by what he sees as a lack of acknowledgement of Jewish grief and fear. And he noted that he now sees dozens of people around him wearing kaffiyehs, the checkered scarves symbolizing Palestinian liberation.

“The past few weeks have been the most isolating, saddening, maddening experience that I’ve ever had,” Kestenbaum said. “I cannot turn to a single faculty member or professor to confidently and safely express my views and opinions.”

After the attack, he flew to Israel, where he attended a friend’s funeral, played the guitar at hospitals treating the wounded, and helped dig graves for soldiers slain on Oct. 7. He said he was in a bomb shelter because of an incoming rocket from Gaza when he saw a WhatsApp message announcing a “long live the Palestinian resistance protest” being organized back at Harvard in response to a deadly explosion at a Gaza hospital.

Kestenbaum said he responded to the message challenging the description of the hospital explosion, and “was told I was propagating Israeli propaganda, that I was callous toward the lives of Palestinians.”

“It was better for my mental health to be in a war zone in the Middle East than to be at Harvard Divinity School.”

Kestenbaum’s experience is in sharp contrast to those shared by several undergraduates who met Wednesday at J.P. Licks, a popular ice-cream parlor at the edge of Harvard Yard. They spoke on the condition their last names not be used to avoid getting further embroiled in the campus tensions that they say have largely been misrepresented by national Jewish groups and news outlets.

A junior named Meredith, who is Shabbat chair of Hillel and co-chair of the J Street U chapter, noted that the university had sent a “mental health wagon” with counselors to Hillel for two weeks and convened a panel with top administrators “to just hear how Jewish students are feeling.” She said there has been too much focus on the pro-Palestinian students who signed statements blaming Israel for the Oct. 7 attack and the backlash against them.

“These are not small shows of support the university is giving, but all the Jewish world can see is that the university formed the doxxing task force the day before the antisemitism task force,” Meredith said.

“What’s driving me crazy about this is that nothing we do on this campus matters,” she added. “The Israeli government doesn’t look at Harvard and make decisions based on what Harvard is saying.”

The students said, however, that they are struggling with the stridency and sometimes blatant antisemitism of the posts on Sidechat, an anonymous message forum that requires a college email to access. And, generally, by people trying to pigeonhole them into “for” or “against” Israel or Hamas when their feelings about the situation are not so simple.

A junior named Serena said she had hosted a Shabbat dinner in a dining hall last Friday “against genocide in Gaza” — carefully wording the invitation (not “the genocide in Gaza”) to avoid implying that she thinks one is underway.

She did not love the feeling of “being pulled into an in-group,” Serena said. “I wanted to be an individual.”

Josh, a ponytailed sophomore involved in the outdoors club, said the war “plays almost no role” in his day-to-day life — except for all the off-campus interest in what is happening at Harvard.

“I have experienced half a dozen people who I’m not in contact with regularly — my parents’ friends, my aunts and uncles I never talk with — texting me like ‘wow Harvard is really doing the wrong thing, I hope you’re safe,’” Josh said. “I’m literally just trying to get through midterms. I’m doing fine.”

George Washington: ‘They don’t see their pain’

WASHINGTON — Arie Dubnov, chair of George Washington University’s Israel studies program, keeps a quote on the filing cabinet next to his desk from George Mosse, a Jewish historian who escaped Nazi Germany: “This course is designed to rid you of your slogans,” it says.

There has been plenty of sloganeering at GWU. The campus chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine made national headlines for projecting “Divestment from Zionist genocide now” on the side of the library, and chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, Zionism has got to go” at a rally. Pro-Israel students, meanwhile, gathered outside the Lincoln Memorial to sing Am Yisrael Chai — “the people of Israel live.”

But not in Dubnov’s seminar on the history of Zionism. “This class is for people genuinely trying to learn,” said Sabrina Soffer, a junior from San Diego. “That’s what’s so beautiful about it.”

Soffer, who writes a column for the student newspaper, is one of Israel’s staunchest advocates on campus, and recently appeared on Fox News, where she described the library projections as “absolute antisemitism.”

She worries that speaking out has put a target on her back. Her mother suggested she stop wearing her Star of David pendant, and when she was studying at Starbucks the other day and found herself sitting next to a woman in a kaffiyeh, she said she suddenly felt concerned about her necklace and the Hebrew stickers on her laptop.

“I was like, ‘I should get out of here,’” Soffer said. “You never know when somebody can just do something.”

In contrast, Celia Little, a sophomore who chairs the campus chapter of J Street U, went out of her way to compliment the kaffiyeh of a woman who came to the off-campus cafe where Little works after a protest.

“There was so much love and gratitude for me saying that,” Little recalled. “There’s so much hate going around right now and it just reminded me that like, we’re all just trying to get through the day. We’re all people.”

At the same time, Little said, some pro-Palestinian slogans feel a bit more sinister to her than they did before the war.

“People saying ‘river to sea,’ I used to feel fine with it,” Little said. “Now I’m like, oh, they mean — or some people mean — killing Jews to get that land back.”

Rabbi Yudi Steiner and his wife, Rivky, have been hosting meals at the Chabad house on campus every night since the attack. Steiner, who has been on campus for 15 years, said he has always assured parents that there is no unabashed antisemitism on campus despite a series of incidents in recent years that garnered national attention.

“I’ve been saying, ‘Stop scaring the kids,’” Steiner said. “Each case is specific, complicated.”

The past few weeks have felt different, if still complicated. Steiner said most students are not worried about their physical safety but describe a new kind of psychic pain, a feeling that their friends and classmates don’t understand why they are so upset.

“They’re scared about what their friends, their sorority sisters, their fraternity brothers — non-Jewish — think about the situation,” Steiner said. “They have a very strong sense that they don’t see the events the same way, that they don’t see their pain.”

Dubnov, who is Israeli and teaches the seminar on Zionism, said that he and faculty members from the Middle Eastern studies department had offered special events to help students process news from the war. And that some Jewish colleagues had complained that he joined a panel with colleagues who are harshly critical of Israel.

“I’m the last one to say there is no hatred — there’s a lot of hatred and it’s increasing,” he said. “Students are coming with a very strong expectation that they’ll take a side. Too many kids are coming with exclamation marks and not enough kids are coming with a question mark.”

Tulane: Burning the Israeli flag ‘is an act of hate’

By Leah Jablo

NEW ORLEANS — Competing expressions of solidarity were scrawled in fading sidewalk chalk along the pathways of the Berger Family Lawn at Tulane University. “Bring them home now,” said one, referring to the Israeli hostages being held in Gaza. A hundred feet away were dozens of names of Palestinians killed by Israeli airstrikes.

Tulane was founded by Jewish businessmen in 1834 and an estimated 44% of its undergraduates are Jewish, leading to the nickname “Jewlane.” Dueling rallies erupted in violence Oct. 26, when one student stopped another from burning an Israeli flag.

The student who disrupted the flag-burning is Nathaniel Miller, a sophomore from Washington, D.C., who chairs Tulane’s Israel Public Affairs Committee and said he was struck in the head by both the flagpole and a megaphone during the clash. In the days since, Miller has penned a letter to the editor of his school newspaper; organized an Israel Unity rally; written thank-you notes to politicians supporting Israel; and received threatening messages on Instagram.

“Accounts on Instagram with no followers DM me telling me to watch my back,” Miller said. “But I have to say that I also received overwhelming support from hundreds of people on Instagram. It just really amazes me how much the Jewish community looks out for one another.”

Miller, who is 21, said he owes his very existence to Israel because his grandmother fled to pre-state Palestine from Poland in the 1930s, when “there was nowhere else to go to.”

He said he understands that flag burning is protected under the First Amendment, but that “coming to the most densely Jewish neighborhood in all of Louisiana to purposely burn the flag of the only Jewish state is an act of hate.”

Members of Tulane’s pro-Palestinian groups declined to be interviewed, but in statements following the Oct. 26 protest complained about media coverage that made it seem like “an attack on Jewish students.” They said pro-Palestinian activists had been “facing verbal threats, doxxing, and intimidation.”

Meanwhile, Chase Turnof, an 18-year-old freshman, said the director of his dorm asked him to take down the Israeli flag in his room — which was visible through the window — after his roommate complained. Turnof said he wished the roommate had talked to him about it first.

“I would have appreciated it if they could have been more direct,” Turnof said. “Considering all the athletic flags you can see from dorm windows, it seemed off.”

Among the hundreds of students attending Thursday’s Israel Unity rally was Katherine Hudson, a sophomore from Knoxville, Tennessee, who works at Tulane Hillel, is a member of a group called Tulane Jewish Leaders — and who just completed her conversion to Judaism on Oct. 15.

Hudson said she was 5 years old when she first asked, “Daddy, how do I become Jewish?” and that she probably first learned about Judaism from the Rugrats specials. She said she chose Tulane because of its large Jewish population and Jewish studies program.

It’s an awkward coincidence that her years-long process of studying for conversion culminated right as the war broke out. The rabbis at the ceremony asked her how she planned to respond to it.

“It’s difficult to enter the community officially at this moment,” Hudson said. “You can prepare yourself for antisemitism as much as you want, and you can read every scholarly book about it, and you can know everything about it intellectually. But it’s so different when you actually experience it.”

USC: ‘There’s a story of educating others about us’

By Louis Keene

LOS ANGELES — Talha Rafique, a Pakistani-American who broke off from a pro-Palestinian protest to engage a group of Jewish students on the University of Southern California’s quad the other day, did not know that one of them, Andrew Turquie, had a friend being held hostage in Gaza.

Turquie, who spent a gap year before college as a volunteer medic in Israel, did not know that Rafique had recently been subjected to anti-Muslim slurs on campus.

The two went back and forth about the war between Israel and Hamas for about a half an hour as the sky above them turned from pink to violet.

Rafique tried to convey that proclaiming “Free Palestine” wasn’t necessarily calling for the end of Israel, much less Jewish extermination. But Turquie, furious that school administrators hadn’t taken a harder stance against the protest, couldn’t hear it any other way.

Still, they shook hands — and exchanged phone numbers. They both said they planned to continue the conversation.

USC is about 10% Jewish, and includes a vocal contingent of Israeli Americans. But a video of USC students taking down posters of kidnapped Israelis drew national attention, and an Instagram post of kaffiyeh-masked students chanting “There is only one solution — intifada revolution,” sparked complaints that the slogan was reminiscent of the Final Solution.

Turquie, a junior who attended a Jewish high school in Los Angeles, said that before Oct. 7 he was not involved in Jewish activities on campus. In the weeks since the attack, however, he has led his fraternity to raise $2,700 for Magen David Adom, the Israeli volunteer ambulance service, and created a WhatsApp group called USC for Israel that now has 300 members.

On Tuesday, he was part of a group that showed up at 8 a.m. to plaster the brick walkways of the quad with posters of the Israeli hostages and blue-and-white balloons. One of those posters depicts Daniel Perez, a friend Turquie met during his gap year whose entire tank battalion was killed or kidnapped Oct. 7.

“Some of my best nights in Israel were going out with him,” Turquie said. “It’s shocking to see after all these years, when it’s the biggest massacre since the Holocaust, and the picture you see with that description is a friend you know.

“When this happened,” Turquie added, “I realized that there’s more to the Jewish story than just us — there’s a story of educating others about us.”

Rafique, the Muslim student who had been debating Turquie, said later that he had co-founded a food charity in 2021 with a Jewish student who had gone on a Birthright trip to Israel. He said he had tried not to let the fact that the student probably considers himself a Zionist — a word that represents displacement and domination to many Palestinians and their supporters — get in the way.

“‘Zionist’ is misrepresented, I think, the same way as ‘intifada’ is,” Rafique said, using the Arabic term that for the Palestinian uprisings that included suicide bombings of buses and cafes.

“Some people who say ‘intifada’ mean the eradication of Jews. Some people who say ‘Zionist’ mean the eradication of Palestinians,” Rafique said. “But intifada, by definition, isn’t calling for the end of Jews. The word means to shake off. Shake off from what? From whatever is attacking you.”

Similarly, he understands that the phrase Allahu Akbar — Arabic for “God is great,” and what Hamas terrorists are seen shouting in videos of the Oct. 7 attack — could be traumatizing for Jews, including Turquie and the others he had tried to engage in debate on the quad.

“But ‘Allahu akbar,’ I say that five times a day,” Rafique said, referring to the Muslim prayer cycle. “That word, and that God, is why I had that conversation.”

Rutgers: ‘Everyone minded their own business, before’

By Adam Janos

NEW BRUNSWICK, New Jersey — Omer Nativ, a junior who moved from Israel to the United States at age 6, said she could not sleep for the first two weeks after the Oct. 7 attack. In her initial grief, she said, she found it easier to connect with fellow Jews than with some of the non-Jews she normally considered part of her inner circle, like her roommate and other sorority sisters.

“It was hard seeing her go on with her life as if nothing happened,” Nativ said of the roommate. “Originally, they put out a post saying they stood with Israel,” she said of other friends, “but then they got targeted, so they said they didn’t want to be involved anymore.”

Nativ, who is 20, said she got dressed up for the homecoming game against Michigan State a week after the attack, but then didn’t feel right about going. She has since organized a bake sale outside Hillel to benefit Magen David Adom.

“It felt so empowering,” she said. “We had one kid steal a vanilla cupcake and scream ‘Free Palestine.’ But I didn’t care.”

Rutgers has 6,400 Jewish students, according to Hillel International, the second-most (after the University of Florida) of any public university in the country. The main artery of campus is College Avenue, where within a mile-long stretch sits the Center for Islamic Life and the Chabad of Central New Jersey. Undergrads in pastel hijabs stroll past colonnaded sorority houses drinking iced matcha lattes while street evangelists hand “Jesus Saves” trifolds to those running late to class.

The “Peace is Possible” coexistence group that Or Doni runs with a Palestinian student took a hiatus after the Oct. 7 attack. Doni instead found himself calling Israeli friends who were on the brink of deployment to Gaza — and feeling guilty about not being in the Israeli military himself.

“I don’t feel bad because I want to fight or kill people. I just feel bad that someone is risking their life while I get to sit here and worry about my organic chemistry test,” he explained.

“I’m a humanist. I want to go into medicine. But seeing how many people want my family gone and dead, both here and in Gaza, makes me rethink things,” he added. “It’s been interesting: watching myself get tribalistic, and trying to prevent it, but to also recognize why it’s happening.”

Daniel Mann, a sophomore from Skokie, Illinois, is something of a magnet for reactions to the war because of his yarmulke. A professor he does not know came up to him in a park to express sympathy for the Israeli cause, Mann said. Then he walked past a group of students on the street and heard one of them whisper: “Israel is not real.”

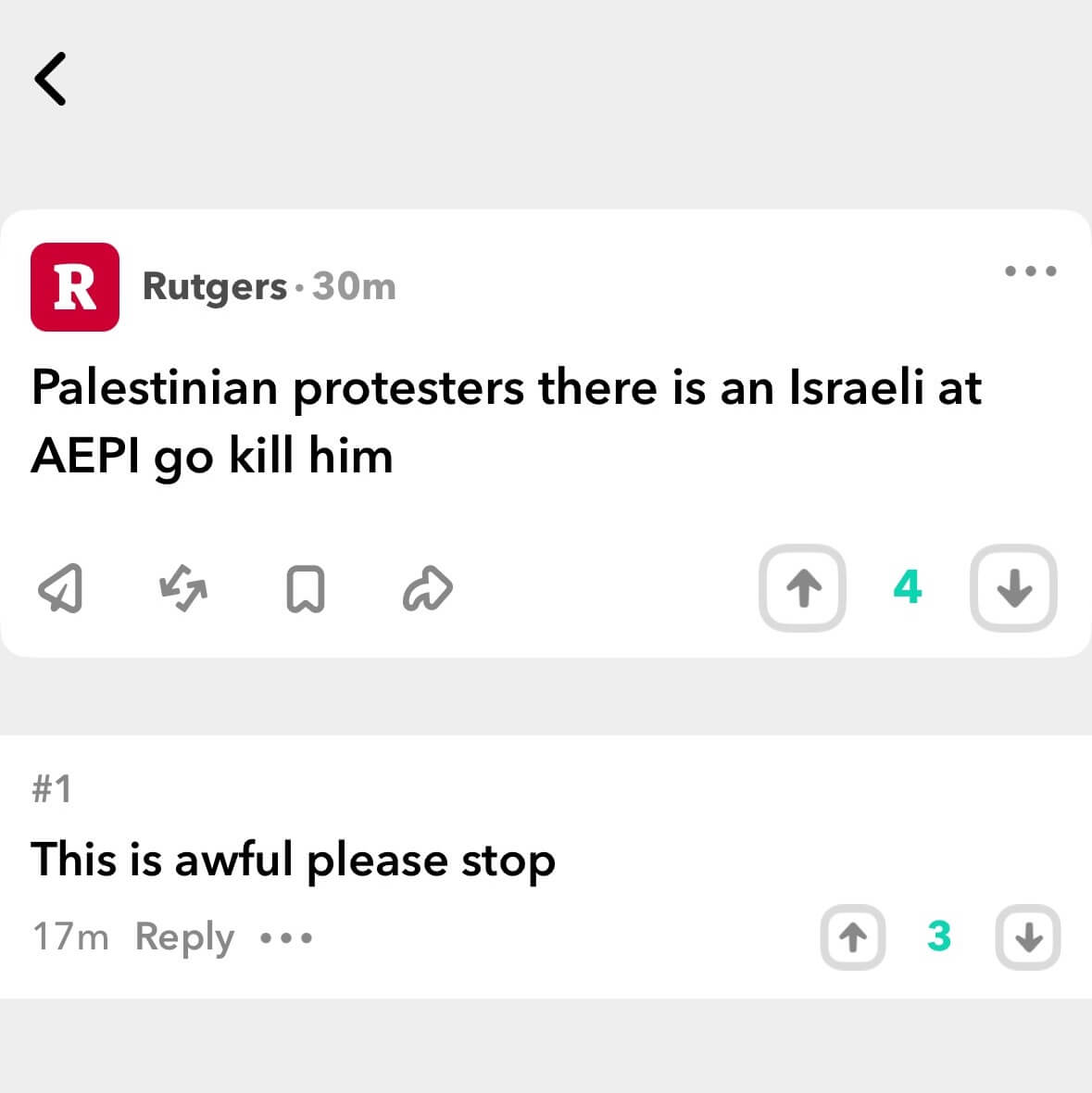

On YikYak, an anonymous social media app popular on campus, Mann said violent comments targeting Jews have become more commonplace, like one on Oct. 12 that said there was an Israeli at the Jewish fraternity AEPi, and urged: “Go kill him.”

And in his Israeli-Palestinian Conflict class, the first lecture after Oct. 7 devolved into a shouting match that led the professor to oust some students and the police to be summoned.

“Before the war, we were all OK with each other,” Mann said. “Everyone minded their own business, before.”

Columbia: ‘We’re all still grieving’

Columbia University was one of the first campuses to make international headlines after the war, when a 19-year-old assaulted an Israeli graduate student putting up “Kidnapped” posters in Butler Library four days after the attack. The assailant, who was not a student, was arrested and is slated to appear in court at the end of the month.

In the days since, a group called “Accuracy in Media” has regularly parked a billboard truck near the Morningside Heights campus beaming photos and names of pro-Palestinian students with the caption: “Columbia’s Leading Antisemites.”

The campus police have generally chased the truck away for double-parking or causing unrest. On Thursday, a group of Jewish students unfurled a banner that says “This is a sukkah of peace” to block the view of the truck’s billboard.

Nomi Richardson, 19, a Jewish and trans student who is majoring in political science, said she has felt “politically lonely” on campus and had unfollowed classmates who made excuses for Hamas on Instagram or justified the Oct. 7 terror attack as resistance.

“People on both sides tend to criticize anything they see as less than 100% supportive of their side, especially on the pro-Palestinian side,” Richardson said. “I want everyone to live in peace and have their own state and be able to have freedom. When I say that, pro-Palestinian activists on campus think I am a colonizing racist, and pro-Israel students on campus think that I am making excuses for terrorist groups.”

On the other side is a graduate student in the school of social work who wore a red mask over her face to make sure she would not be identified and gave only her first initial, L., for fear of becoming the next target of the so-called Doxxing Truck. L. said that she spoke about what is happening to her family members in Gaza during a Columbia walkout two weeks ago, only to be disrupted by counter-protesters laughing and taking selfies with Israeli flags.

“I’ve been told that I support raping women and that it was a good thing that Hamas killed Israeli civilians,” L. said. “Somebody even told me that me bringing up the deaths of my family was antisemitic.”

She said she had filed complaints with the university but has gotten no response. She also said she has started carrying pepper spray.

“My friends who’ve been doxxed on the truck have been getting death threats,” L. said. “One of them was told that she should be used as target practice by the IDF.”

Inside the school of social work, Professor Amy Werman has a sign on her office door with a large red heart that says, “I offer anyone who is hurting during this turbulent time in our world a safe and compassionate place to share.” Inside the office is a giant rainbow flag with a Star of David in the middle that Werman got at a Tel Aviv Pride celebration.

She has been teaching at Columbia for 14 years, and said, “these feelings of antisemitism, anti-Israel or anti-Zionism have always been bubbling under the surface.”

“If you mention Israel, it’s automatically met with ‘What about the Palestinians?’ If you mention Jews, it’s always conflated with Gaza, the West Bank and colonization,” she said. “It doesn’t deflate me or defeat me. It just makes me feel more resolute that I have to defend my people.”

Outside Werman’s office, the school had been plastered with flyers bearing a QR code that led to a three-page “Statement in Support of Palestinian Resistance” that referred to Israel as a “settler-colonial entity.” There were more than 80 such flyers, hanging in bathrooms and on vending machines, on tables in the school library and in the elevators.

But on the center of Columbia’s campus, Yola Ashkenazie, 21, and some of her friends were arranging 238 red roses — one for each of those believed to be held captive by Hamas — in a circle next to three Israeli flags.

Ashkenazie said that she had friends killed at the Nova Music Festival on Oct. 7, and has been unsettled by pro-Palestinian chants — and feeling “lucky that I don’t look stereotypically Jewish.”

“We’re all still grieving. We’re three weeks out from people who we love that were murdered,” she said. “People here aren’t understanding that we’re all just students in our young 20s, who just experienced the biggest tragedy of their lives.”

U. Michigan: ‘I could have been there’

By Debrah Miszak

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — There is a large rock near the campus of the University of Michigan that is something of a barometer of what’s going on. Students paint it with the social justice slogan of the moment, or with the campus mascot before big football games.

On Wednesday, the word “Yisrael” in the middle of “Am Yisrael Chai” had been crossed out with red paint, as had a Star of David.

About 14% of Michigan’s students are Jewish, and there is also a large number of Palestinians and other Arabs from the Middle East. More than 1,000 faculty and staff members have signed onto a letter condemning the university president for not mentioning Palestinians in an Oct. 10 statement about the war, and the student government passed a resolution Wednesday calling for a halt in harassment of activists on both sides of the conflict.

“I think it’s a lot of groupthink,” Sari Rosenberg, the junior who heads Hillel, said of the open letter. “It just got sent out to the department, and then they just signed their names on because it seems like the liberal, progressive thing to do. I don’t truly believe that they’re supporting Hamas, and that they hate all Jews.”

Rosenberg, a women’s and gender studies major from New Jersey, said she feels physically safe at Hillel and Jewish events on campus, but has been concerned about what she called “mental safety” for herself and others.

And though she was glad she decided to proceed with Hillel’s annual Nice Jewish Ball dance, Rosenberg said it has been hard to watch fellow students get back to normal when she and others are still so consumed by the events in Israel and Gaza.

“Even though some people are pretending that the war is over, for many of us it’s still at the forefront of our experience at school,” she said. “So, sometimes it’s difficult to continue on with normal life, such as going to parties or bars and hanging out with friends, when there’s work to be done for the war.”

At the root of the discomfort, Rosenberg said, is a misunderstanding of the link many Jewish students have to Israel. Some have lost friends and family in the war. She herself has been shaken thinking about what would have happened if Hamas had attacked two months earlier, when she was interning at Hillel Tel Aviv through a Young Judea program called Amirim.

“I was there all summer,” she said. “I could have been there. I could have been there on winter break. I would’ve been scared, you know?”

Brooklyn College: ‘I do think the war needs to end first’

Serving 12,000 undergraduates on a stately green campus in Flatbush, Brooklyn College is a melting pot that has been threatening to boil over since Oct. 7.

A United 4 Israel vigil was disrupted by pro-Palestinian protesters chanting “Your 9/11 is our 24/7.” A New York City councilwoman was arrested after illegally brandishing a gun at a pro-Palestinian protest where she said, “If you are here, standing today with these people, you’re nothing short of a terrorist without the bombs.” Student organizations have called on the president to resign over her connections to the councilwoman. Campus security is on high alert.

A pair of New York Police Department officers leaned against the black railing in front of the Hillel building the other day, hands in their jacket pockets. Alec Wolf, a student in a black hoodie and a baseball cap, approached with two cups and a plastic bag dangling from his wrist.

“I got these two hot cocoas,” offered Wolf, a student who grew up in Virginia’s tidewater region. “And I hope y’all like black-and-white cookies.”

Moving to New York “was a huge dream for me,” Wolf said, after being the only Jewish kid in his elementary and high schools. But he’s been upset to see classmates tearing down hostage posters, and at vigil for the Israeli victims the other day, a counterprotester gave him the finger.

“I never felt like, when I was in Virginia, I was going to be attacked because I was Jewish; I never felt like I needed to tuck my chai necklace,” Wolf said. “But now that I’m in New York City, I do tuck my chai necklace when I get on the subway or leave the Hillel building.”

Aharon Grama, who was born in Brooklyn but lived in Israel for most of his childhood, graduated from the college last spring after two years as co-president of the student government, first sharing leadership with a Muslim woman who kept her hair covered.

It was “groundbreaking,” Grama said, to have a formerly “religious Jew who served in the IDF with a Muslim hijabi girl as co-presidents.” But in the last month, Grama, who now works in the college’s administration, said he has witnessed a lot of the work they did together “fall apart” and watched former friends — Muslims and Jews — distance themselves from him because of their presumptions about his politics.

“There was dialogue; there were conversations happening,” Grama said, mentioning town halls they held for Muslim and Jewish students, and interfaith clergy meetings. “It was completely different than what these last few weeks have brought upon us.”

One afternoon, he walked by a vigil for Israeli victims on his way out of the office, and had someone yell at him, “You should be ashamed of yourself for standing on the side and not joining us.”

He’s also seen Jewish students remove non-Jews from campus WhatsApp groups and heard a rabbi accuse pro-Palestinian protesters of supporting terrorism.

“That’s not the kind of environment that I tried to cultivate,” Grama lamented.

But Grama said he has also had some moments of empathy and connection, like when he got a long text message from a friend who belongs to the Muslim Student Association.

“It breaks my heart when I see the harmony of campus getting lost and the bonds that we’ve created get shattered,” the text said. “Hoping we can all work together to overcome this,” it concluded, with a prayer emoji.

Grama is hopeful that his student-government successors will be able to help repair relationships damaged in recent weeks.

“I do think that the war needs to end first,” he said. “But yes. I think it is possible.”

UC Berkeley: ‘We have the people, but not the unity’

BERKELEY, Calif. — Noah Rothman, a senior anthropology major and president of the campus Hillel, would like to set up a public conversation between the University of California, Berkeley’s director of Jewish studies and a professor of Quran whose class Rothman took last year.

“It will be amazing if it happens, but there is so much anger and grief right now that some people might get upset, too,” he acknowledged.

Rothman is also thinking about planning a Hillel pool party or escape room outing — something fun. Attendance at Hillel events has dropped since the attack.

“People are more willing to divide over Israel than they are to unite over the fact that we are all Jews in Berkeley,” he said. “We have so much in common — being from California, looking for jobs. It’s just hard that people are getting mad about who says what about Israel.”

Rothman, who is 25, went to Israel after high school for a year and ended up staying five. He joined the Israel Defense Forces and served in the occupied West Bank. “I know what that fight looks like,” he said, “and no one would tell you it’s worth separating yourself from other Jews. So why are we breaking ourselves up from within?”

Berkeley was home to anti-Zionist activity that some saw as leaching into antisemitism long before the war broke out. A total of 19 student groups at the law school have over the past year voted to bar Zionists from speaking on campus, which led a professor to write in The Wall Street Journal: “If you don’t want to hire people who advocate hate and practice discrimination, don’t hire some of my students.”

Hundreds of Berkeley students joined a nationwide pro-Palestininan walkout on Oct. 25. Rothman went to watch.

“I was impressed,” he said. “They have a lot of unity. We have the people, but not the unity. Do you counterprotest? Do you not?”

After a pause, he added: “I’ve never been an activist for Israel, that’s just not me. But since 10/7 I’m expected to speak for everyone at Hillel. It is very hard to find the right thing to say. And then encompassed in what you do say is everything you don’t say, you know?

“There’s no room for saying, ‘Yes, I support Israel, but I’m also concerned about innocent people in Gaza.’”

At Hillel’s weekly Wednesday night barbecue of chicken, potato salad and those wicked brownies with the frosting, Rothman’s eyes worked the crowd: Definitely fewer people than before the attacks, he said. But there were a couple of newbies by the tables clad in Cal blue and yellow.

One was a graduate student who was afraid to give her name for fear of compromising future job prospects — but who said she has started wearing both a small Star of David and a chai pendant since the war began.

“I feel like our main identity now is ‘Jews’ and once they see that, that is all they see,” the student said. “So I feel like since I can’t be open about my feelings over all of this, wearing these makes me feel more comfortable. They feel like my suit of armor.”

In one class, she said, she sits next to a young woman she has seen online celebrating the deaths of Jews on 10/7. “I can’t see the board without also seeing her,” the woman said. She began to cry and two other grad students reached to comfort her.

University of Chicago: ‘I’m genuinely afraid’

CHICAGO — Most days for the past three weeks, the Students for Justice in Palestine group has set up a table on the University of Chicago’s leafy quad with signs saying “Israel is Starving One Million Children” or “Israel Bombs Hospitals.” Members of the group chant, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” which many Jewish students hear as a desire to exterminate Israelis.

As on other campuses, Jewish students have taped posters of Israeli hostages on light posts.

Leah, a 22-year-old senior who spoke on the condition she be identified only by her middle name, feels assaulted by the rhetoric. She has stopped crossing the quad to get to class, where someone who sits behind her has a sticker on their laptop that says “Free Palestine, Destroy Israel.”

Her sister, a sophomore at the school, “has called me crying multiple times after crossing the quad,” Leah said. “I’m genuinely afraid.”

And she has been unable to talk about the situation with close friends who are not Jewish.

“I don’t know how to start that conversation where you disagree with my core fundamental values about Israel,” Leah said. “I feel like I’m going to be judged and people will think I have no morality and don’t care about innocent lives.”

Rabbi Anna Levin Rosen, executive director of the university’s Hillel, said that all the students she is working with “feel unsafe emotionally” right now.

“It’s very difficult to comprehend seeing Hamas as a force for freedom, and that seems to be a dominant opinion here,” she explained. “The pain of being written off by friends, and feeling pressure to choose between their public Jewish identity and friendships has created social pressure that is unbearable.”

Chabad and Hillel staged a vigil on the quad Oct. 19. Rabbi Levin Rosen gave a sermon-like speech about “nation not lifting up sword against nation.” SJP members drowned her out with chants through a megaphone, the rabbi said, and a university dean dressed in the colors of the Palestinian flag stood with the SJP group.

“There is a lot of disappointment on campus that our free speech was interrupted,” the rabbi said. Days later, some 400 people signed an open letter demanding that the university take action to prevent a similar disruption from happening again.

On Wednesday, the university president sent a message to the community reiterating key aspects of the school’s free-speech principles, and pledging “disciplinary action when needed.” The rabbi said she was gratified by the statement.

But Leia Gluckman, a third-year student from Los Angeles, said all the hullabaloo has left her newly afraid to voice her opinion in class discussions or assignments. She has seen a classmate who sits next to her at SJP rallies.

“I don’t want to have to justify my opinion on something, let alone my existence,” Gluckman said. “That’s what it’s become right now. It is impacting my sense of security and my academic performance. We can’t keep hiding. We hid before, more than once.”

Cornell: ‘I don’t want people to pity me’

ITHACA, New York — Ezra Galperin, an Orthodox freshman from Brooklyn, barely got to know Cornell before it got this exhausting, before it got this loud.

On Friday, with Cornell having taken the extraordinary step of canceling classes for a day of “community rest,” Galperin was sitting in the Center for Jewish Living. Outside, workers were installing the security cameras that New York’s governor promised on her visit to campus days before.

Police vehicles were parked in front of the building, as well as at 104West!, the kosher dining facility, and the campus Chabad. Uniformed officers were walking up and down the corridors of White Hall, the building that houses both Jewish studies and Near Eastern studies.

“Ironically,” Galperin said, “the CJL has become the safest place on campus.”

When the online threats were posted Oct. 29, Galperin was studying in the library after finishing dinner at 104West!. His father had been on campus for parents’ weekend and had just finished the four-hour drive home. He offered to get right back in the car to rescue his son.

“My father asked me to please not wear my kippah outside,” Galperin said. “I was terrified. I knew the majority of students wouldn’t have endorsed such a thing but I had no way of knowing if the person was my neighbor, someone I was safe around. I put my hood up and went back to my dorm for the rest of the night.”

Later, a campus rabbi “made the rounds and dropped off some soup,” Galperin recalled. “My friend from Israel texted to ask me if I was OK. Me, here at Cornell.”

Painfully, Galperin shared that many of his friends had also taken off their yarmulkes or other Jewish symbols until the student who posted the hateful messages was arrested the next day. He described a mix of feeling fearful and supportive at the same time, and said the Jews on campus had grown closer recently — over meals, discussions and services.

“From everyone else, there’s a sense of pity,” he said. “I don’t want people to pity me. I’m proud to be Jewish.”

But another Jewish student, a junior from Paris who is majoring in government and German studies, described feeling anxious as she walked past graffiti and posters on campus comparing the Israeli government to Nazis. She noted that her grandmother had fled Romania in the 1930s.

“Most of the time, the people I notice who are using the word genocide have no idea what it means,” said the student, who is on the board of a publication focused on women in the Middle East and North Africa, but spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the climate on campus right now.

“Maybe I’m naive but I never thought something like this could happen at Cornell,” she said. “I grew up in France where there is a lot more antisemitism, so when I got here, I felt much more comfortable talking openly about being Jewish — even with people who aren’t Jewish, which is not something I would do in France.”

“Now, I feel much more guarded,” she said. “My friend asked me if it was safe to go to Shabbat dinner. I’m not sure. But if I don’t go,” she said with a long pause, “I’ll let the bad guys win.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO