How Albert Einstein inspired Mandy Patinkin to rescue refugees

‘In my life,’ said Patinkin, ‘what he’s known for is not the theory of relativity, but the theory of relatives’

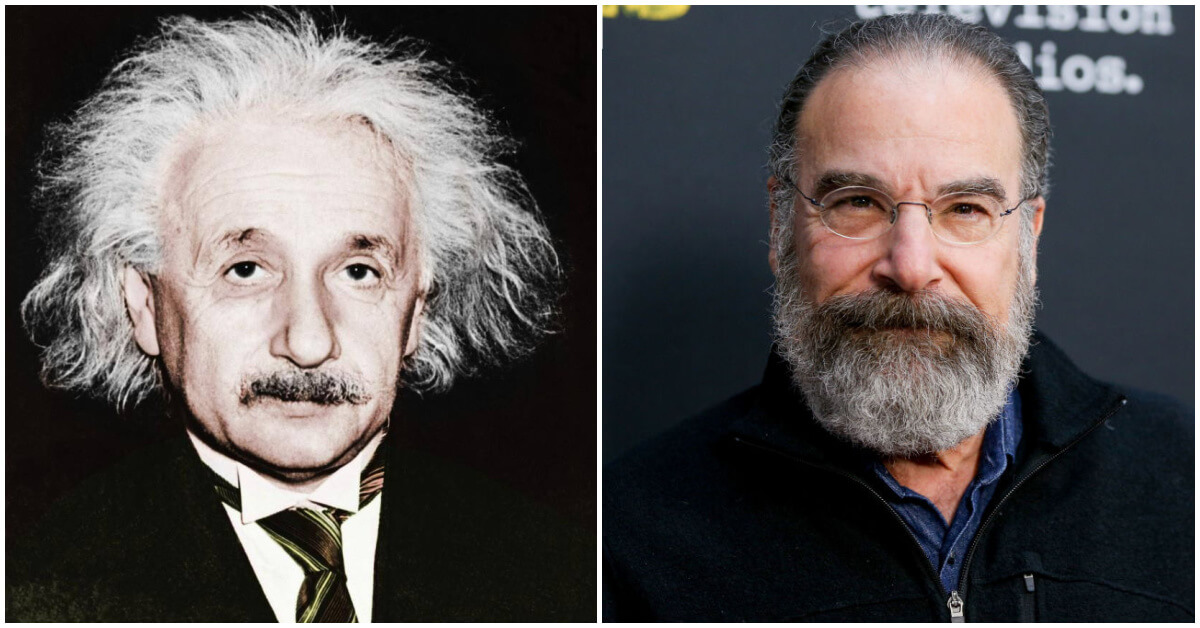

Albert Einstein launched the International Rescue Committee to help save refugees. Mandy Patinkin is now its spokesperson. Photo by Albert Einstein Archives/Getty

Editor’s note: This essay was adapted from The Einstein Effect, a new book about the modern-day relevance of the world’s favorite genius.

While Mandy Patinkin was in Berlin filming the fifth season of Homeland, the spy thriller TV series, in 2015, some 125,000 Syrians were fleeing their war-ravaged homeland, hoping to seek refugee in Europe. The day shooting wrapped, Patinkin, then 63 and one of the world’s best-known actors, hopped on a plane to visit a refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece.

“I’m looking at photos of these people in lines, trekking, and they reminded me of my ancestors fleeing the pogroms of Poland and Belarus,” Patinkin told me in an interview last year, recalling his 20-plus relatives lost in the Holocaust. “We were all refugees. And I thought: There but for the grace of God go I.”

Patinkin had reached out to the International Rescue Committee, a refugee aid organization that Albert Einstein helped form in 1933 and that remains one of the largest in the world, helping millions of people across 40 countries. Patinkin said he wanted to volunteer “not as a celebrity, but just as a human being.”

“I want to just go and walk with them and give them water and company and comfort and let them know I’m a human being who cares about them,” was how Patinkin recalled it. “The next thing I know,” he said, “I’m there, and it changes my life.” He has been the group’s ambassador ever since.

I’d arranged this Zoom conversation with Patinkin as part of the reporting for my book, The Einstein Effect, which chronicles some of the less-known ways that the world’s favorite genius continues to shape our lives long after his own death. The journey took me across the United States and to both Israel and Japan. I interviewed dozens of Einsteins – including not one, but two Rabbi Einsteins — as well as celebrities like Patinkin, whose bushy brows added to the expressiveness of his eyes during our 90 minutes together.

During that first visit to Greece in 2015, Patinkin said, he rushed to the edge of the Aegean Sea and saw a boat coming to shore. “It’s all overloaded and everybody’s jumping off,” he recalled. “And a person puts a little girl in my arms with a pink jacket.” She was limp, and Patinkin thought she might be dead.

“All of a sudden, I put my finger in her hand and I feel her squeeze my pinky,” he told me. He took the girl to a medical tent and eventually reunited her with her family. Patinkin was hooked: He’s since gone with the IRC to visit refugees in Uganda, Serbia, Jordan and along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Patinkin’s involvement got turbocharged after the 2016 election of President Donald Trump, who slashed by 85% the number of refugees allowed into the country. “The damage done by the Trump administration was horrific,” Patinkin said. “How do you have the nerve as the descendant of anyone who made it here to say, ‘Sorry, doors closed!’”

He told me a story about his Grandpa Max, his father’s father, who came through Ellis Island in March of 1906 with $3 in his pocket, and eventually became a prosperous businessman.

“He used to say a Yiddish phrase, dos redl dreyt zikh, which means ‘the wheel is always turning,’” Patinkin said. “If somebody on the bottom is knocking on your door and you don’t open it up and welcome them and give them comfort, food and sanctuary and safety, when you’re on the bottom, no one will open the door to you. It’s just clear, moral, ethical behavior. For me, my job for the rest of my life, is to open the doors for others who are in need.”

Einstein to the rescue

The creator of the group that Patinkin now serves as spokesperson for was himself one of the most famous refugees of his generation.

As Nazism took hold in Einstein’s native Germany in the early 1930s, he was named an enemy of the state and barred from his teaching position at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. When he left his homeland in December 1932, Einstein reportedly told his wife, Elsa: “Take a very good look at it. You will never see it again.”

Hitler Youth later tore apart his summer cottage in Caputh. The Nazis reportedly put a $5,000 bounty on Einstein’s head. “I didn’t know I was worth so much,” the scientist joked.

Einstein renounced his German citizenship and was granted residency under the government program EB-1, which gives priority to immigrants who have “extraordinary talent” or are “outstanding professors or researchers.” It has since become known as the “Einstein visa.”

With his own situation secured, Einstein leveraged his celebrity influence to help rescue other German Jews. He gave speeches and spoke at fundraising dinners. He performed a violin concert for the United Jewish Appeal, a philanthropic organization, and served as the group’s honorary chairman from 1939 to 1944. He also used his own money to resettle Jews in Alaska, Mexico and other places willing to take them.

“I am privileged by fate to live here in Princeton,” Einstein wrote in a 1936 letter to Queen Elisabeth of Belgium. “In this small university town, the chaotic voices of human strife barely penetrate. I am almost ashamed to be living in such peace while all the rest struggle and suffer.”

He formed what was originally called the International Relief Association in the summer of 1933 “to assist Germans suffering from the policies of the Hitler regime.” A similar group, the Emergency Rescue Committee, was created in France, and in 1942 they merged to become the International Rescue Committee, whose spokesperson is Mandy Patinkin.

‘The theory of relatives’

Patinkin knew well the history of the organization’s founder. “When Einstein arrived in America,” he said, “he spent his own money to help people get visas, and then he joined the NAACP because he was in shock that everything he ran away from was happening right here with Black people.” For Einstein, Patinkin said, it was “just the same horror that the Jews were escaping.”

Indeed, when a hotel in Princeton refused a room to Marian Anderson, a visiting Black opera singer, Einstein invited her to stay at his home. (The 2021 play My Lord, What a Night reenacts that event.) Anderson returned to visit many times, and the two remained friends until Einstein’s death.

Einstein once personally paid the tuition for a promising Black student in Princeton. And in a 1946 commencement speech at Lincoln University, the nation’s first to grant degrees to Black people, Einstein declared: “The separation of the races is not a disease of the colored people, but a disease of the white people,” adding: “I do not intend to be quiet about it.”

“Being a Jew myself,” he said to a family friend, “perhaps I can understand and empathize with how Black people feel as victims of discrimination.” And: “My attitude is not derived from any intellectual theory but is based on my deepest antipathy to every kind of cruelty.”

As I shared some of this with Patinkin, he shook his head in admiration. “Einstein flees one situation, comes to safety, and immediately has the courage to speak out.”

Einstein’s work with refugees continued throughout his life: In addition to the IRC, he was active in the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and was honorary president of the French-Jewish Children’s Aid Society. In 1949, shortly before Einstein turned 70, children who had been relocated to the United States from a displaced persons camp in Europe knocked on his door in Princeton to thank him. It was a “magnificent birthday gift,” Einstein told The New York Times. A photographer on hand to capture the event, Philippe Halsman, was himself someone Einstein had helped come to the United States in 1940 after the Nazis invaded France.

Patinkin said he was reminded of Einstein’s attitude when he was in Germany meeting with Syrian refugees and asked a woman if she had a lingering sense of fear.

“She said, ‘After what we’ve been through, we are afraid of nothing. I saw death behind me and life in front of me, and I just kept walking,’” Patinkin recalled. “It’s the same thing with Einstein. After what he had been through, what he had just witnessed, he was not afraid to stand up for what’s right — morally and ethically.

“He was intelligent in his soul,” Patinkin continued. “In my life, what he’s known for is not the theory of relativity, but the theory of relatives.”

‘How do we change a hateful heart’

Patinkin, now 70, said he sees “one of Einstein’s greatest gifts” as “his compassion for humanity.”

“God brought gifts because of his intellect and genius that the world will benefit from through eternity,” he added. The mention of God prompted me to ask Patinkin about his own beliefs.

“I’m spiritual,” he told me. “I believe in Einstein’s theory of relativity, which means that energy never dies. That’s what Einstein proved. That energy in Abraham or Moses or my father or Steven Sondheim or Abe Lincoln or anyone on this Earth that you admire, the energy in their cellular matter is out there.”

He said his favorite word is connect. “If you want to connect to the 6 million lost in the Holocaust, all the Native Americans who’ve been lost, all the African Americans who’ve been lost, all those who’ve been treated inhumanely, my fellow human beings, you can reach them, you can gather them, you can be with them. They’re all in the universe in some form.”

I asked Patinkin what he would talk about with Einstein if he were to meet him in the afterlife.

“First I would say, let’s go get some lox and bagels,” Patinkin said with a roaring laugh. “We’d go sit down. And then I’d say to him, ‘How do we address hate? How do we change a hateful heart? How do you undo hate? How do you change someone’s fear of othering? How do we do that?’ I can’t figure it out other than acts of kindness.”

Patinkin recalled the time he met Farhad Nouri, a 10-year-old Afghan refugee, in Serbia. They sat on a bench together with an IRC film crew nearby, and Patinkin asked if there was a message the boy wanted to send to the world. “Yes,” the boy said. “Refugees need kindness.”

Tears appeared in Patinkin’s eyes as he retold the story. “Einstein knew this. So, I would sit with Einstein, and I would say how do we teach a 10-year-old-boy’s wisdom to a world that wants to embrace fear of others, xenophobia, hate, and employ violence toward others. How do we stop that?”

He went on: “We live on a planet where, if we can protect it from being destroyed by human beings, chances are there could be enough space and resources, even as the population grows, to hold an embrace of that humanity long past our lifetime for generations and generations to come.

“And so, I would ask for his practical counsel. I don’t want some intellectual idea, or some scientific explanation of the cosmos and physics that I can’t get a hold of. Instead, I would ask: ‘What do we do?’ And I am certain that he would let me walk away from that lox and bagel sandwich with an action to take. I’m certain. He was a doer. A practical man.”

And so is Patinkin. He hosted a podcast, called Exile, about Jewish lives in the shadow of fascism. He’s performed Yiddish versions of Broadway showtunes in dozens of cities. Like Einstein, he has used his celebrity to speak out against social injustices including police brutality and voting rights.

In recent weeks, he has joined the picket lines of striking Hollywood writers.

When the pandemic struck in March 2020, Patinkin and his wife of more than 40 years, Kathryn, moved into a cabin in the Hudson Valley. Soon their son Gideon began posting to social media fun videos of them squabbling, snacking, playing with their dog, Becky, and doing mundane household chores.

Watching Patinkin change the filter in his vacuum cleaner is nothing short of mesmerizing. He now has 2 million followers across Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter.

“If you have the privilege of having a platform for whatever reason,” Patinkin said, “and you can reach one person, or many people – use that opportunity, use that privilege to speak out for what you believe in.”

A wide smile came across Patinkin’s face. “As Einstein said, ‘A life lived for others is a life worthwhile.’”

Adapted from The Einstein Effect by Benyamin Cohen. © 2023 by Benyamin Cohen. Used with permission of the publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc. All rights reserved.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO