The klezmer band playing as the bullets started flying can’t go back to Highland Park this July 4

Chicago’s North Shore has spent a year mourning the victims of last year’s Fourth of July parade in the heavily Jewish city of Highland Park

The Maxwell Street Klezmer band under a bridge at the Highland Park July 4 parade in 2019. Courtesy of Maxwell Street Klezmer Band

It was supposed to be the year of the parade’s triumphant return. After the pandemic forced Highland Park’s July 4 tradition to take a two-year hiatus, members of the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band climbed up on their flatbed truck last summer and warmed up their instruments, eager to make the crowds along the route dance once again.

“Everybody was just glad to be there,” said trombonist Dana Legg. “It was like a big sigh of relief at the beginning, that here we are finally doing something back to normal.”

But as they began playing “Freylekhs fun der khupe,” an exuberant wedding song and their go-to opener for parades and simchas, a gunman opened fire from a rooftop farther along the parade route. The mass shooting left seven dead — five of whom belonged to Jewish families — and dozens more wounded by bullets or shrapnel. A viral video taken by a parade-goer of the band starting to play and then abruptly stopping as shots rang out, captured some of the chaos.

Though the gunman, now awaiting trial, is not believed to have been driven by antisemitism, Jews in and around Highland Park, a heavily Jewish suburb north of Chicago, have spent the past year grieving and trying to make sense of the horrific turn that morning took.

So has the band, which returned to Highland Park to play a concert at the public library three months later. They hoped to be part of the community’s healing as much as they had been part of its joy. Since its founding 40 years ago, Maxwell Street has been deeply intertwined with the city’s Jewish life, playing more than 1,000 events, including weddings and bar and bat mitzvahs, according to Lori Lippitz, its founder and artistic director. And for at least a decade, it has added Jewish flavor to the city’s July 4 parade, one of the most beloved and well-attended on the North Shore.

This July 4, however, though the band and the city, now more than ever, share a profound connection, Maxwell Street will not play a parade in Highland Park. No one will. Lippitz said she understands why.

“I think it might be very jarring, this year for sure, to just go rolling down the streets where people were shot down,” Lippitz said.“That ground was a battleground. I don’t know when it’s right to roll a parade over it again.”

Chicago’s North Shore and its Jewish community have mourned the dead, nursed wounds both physical and emotional, and tried as best they could to regain a sense of normalcy.

The band, based in nearby Skokie, has coped in its own way, with klezmer, the sometimes doleful and often buoyant traditional music of Eastern European Jews. Its members are committed to performing at other Chicago-area July 4 parades next week. One though, plans never to play a parade again.

Conversations with Maxwell Street musicians in the weeks leading up to this year’s parade — and with others deeply connected to Highland Park’s Jewish community — reveal how the pain of last July 4 continues to reverberate, and how recovery can take many different paths.

But there is commonality too, as the community stricken by last year’s calamity contemplates the upcoming holiday, which to many will not feel like one.

“Everybody,” said Stacey Skolnick, a Jewish day camp director who lives in Highland Park, “has big feelings still about it.”

Mayhem

Before the parade began last year, band members tuned up, jamming with a high school drumline and other musicians slated to perform. As the flatbed began to roll and they struck up the klezmer in earnest, Maxwell Street tuba player Howard Prager noticed people dancing on the sidewalk.

“It felt really great,” he said.

But the feeling would last for only a few bars. They continued to play even as a handful of people began running toward them, against the flow of the parade. Prager assumed a celebrity sighting had caused a stir.

“Then all of a sudden, there are more people. And we see them with panic on their faces, terror in their eyes,” he said. “It felt like a disaster movie.” Alex Koffman, the band’s musical director and violinist who’d served in the Red Army before immigrating from Belarus to the U.S. in 1989, recognized the sound of gunshots.

All the members of the klezmer band made it back to the staging area and into their cars. They drove in a daze to their next parade before anyone could really grasp what had just taken place — and then back home after they learned every other event in the area was ultimately canceled.

As the shooting made national headlines, local Jewish institutions went into crisis mode. There were funerals to plan, families to support. Among the dead were Jacquelyn Sundheim of Highland Park, the b’nai mitzvah coordinator at North Shore Congregation Israel, a Reform synagogue in nearby Glencoe; and Irina and Kevin McCarthy, the parents of a 2-year-old who survived the massacre. Irina McCarthy had been the same age when she immigrated to the U.S. with her Russian Jewish family.

“It was certainly a defining moment for the Jewish community” in Highland Park and the broader Chicago area, said Elizabeth Abrams, assistant vice president of communications for the Jewish United Fund of Metropolitan Chicago. “It seemed that everyone knew someone close who was there, who was injured, who was enduring the trauma of running from the scene.”

Coping

Skolnick, 53, who had loved the Highland Park parade since childhood, had organized about 100 families from JCC Chicago’s “Z” Frank Apachi Day Camp in neighboring Northbrook to march together last year. For months after escaping with her own twin daughters and frantically contacting the families she’d gathered for the event, she felt safe only at home and at camp. She saw danger everywhere and couldn’t stomach watching anything on TV besides children’s programming and shows like Friends.

But there also support — from the city, which connected people with specialized mental health counselors, from Jewish institutions, and from one another. There were hugs and nods of unspoken understanding and a little extra kindness.

As the anniversary approaches, she sees “two schools of thought.” For some people, and she includes herself in this group, “it is top of mind, it has changed who they feel like they are,” said Skolnick. Her anxiety comes in waves, and she was surprised to find it triggered by the warming weather and start of camp. “And then there are other people who are like OK, it’s time to move on, this happens a lot, we hear about it almost every day, it’s time to have a regular parade again and move forward.”

The city of Highland Park — which created a Resiliency Division and began thinking months ago about how to handle the first July 4 after the shooting — has decided against a parade and fireworks. “This is an extraordinary year,” said city manager Ghida Neukirch. “We felt like it was important to have a variety of different events where people could come together how it’s most meaningful and how it’s most comfortable for them.”

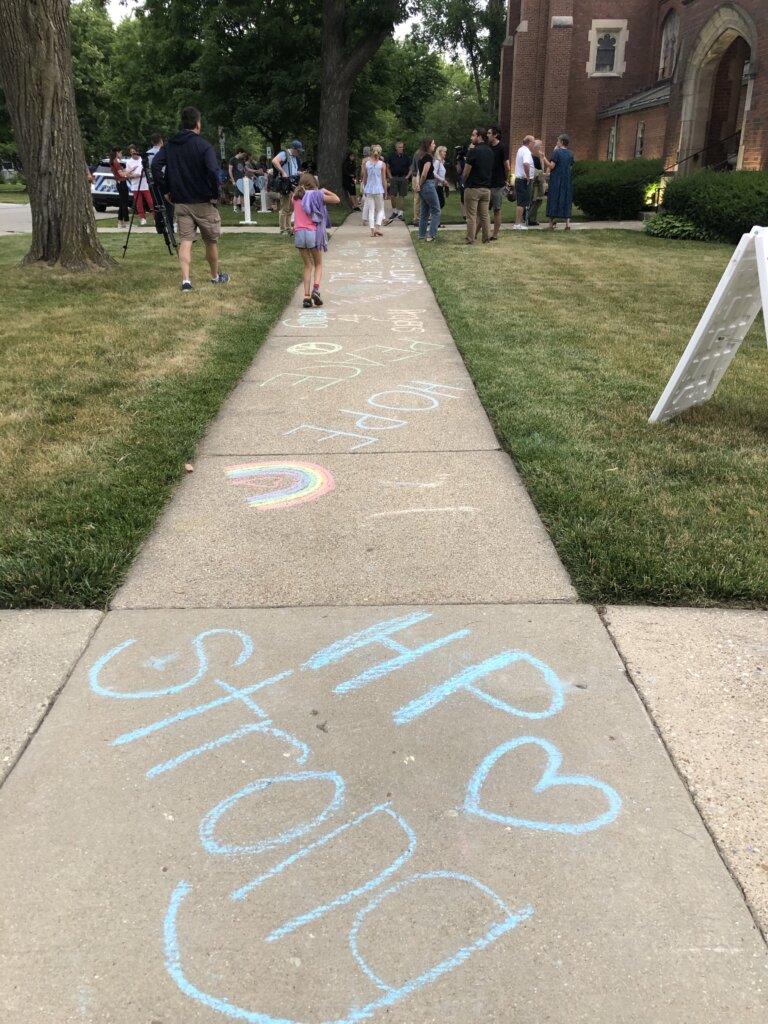

The day will begin with a remembrance ceremony at city hall (which will also be live streamed for anyone who wants to watch but isn’t comfortable attending in person) and a community walk that is decidedly not a parade.

“It’s not designed to be something people view, it’s designed to be something that people do, so that as a community we are actively traveling this journey together,” said Amanda Bennett, communications manager for the city.

They’ll retrace the traditional parade route and “reclaim that as a community,” Bennett said. A community picnic with games and activities will follow. And finally, evening entertainment will include a concert by Gary Sinise and the Lt. Dan Band and a custom drone show in lieu of fireworks.

Most of the day’s events require registration, part of an enhanced security plan. As of mid-June, Neukirch said the city had about 1,600 people registered for the remembrance ceremony, 2,000 for the community walk, and 3,200 for the evening entertainment.

Skolnick and her friend, Ilana Carp — assistant director for program marketing at JCC Chicago and a fellow single mother who was part of the camp group last year — have been talking about taking their kids to the drone show together. But neither can fathom participating in the community walk. In the absence of kids on bikes and musicians on floats, Carp said, “I’m imagining it’s going to be this quiet walk, which just feels hard and heavy.” For Skolnick, “It very much feels like a funeral procession,” she said. “I would never bring my kids to that.”

And some aren’t ready to gather with larger groups at all. “I can’t imagine being in a crowd,” said Ron Krit, the national director of the Life & Legacy program at the Harold Grinspoon Foundation. Krit lives in Highland Park and was at the parade last year with his wife and the younger of his two sons. He’s not there yet, but one day, “I will definitely go to a parade again,” he said. “I don’t want one horrible person to ruin a national pastime.”

Neukirch and her colleagues understand that as thoughtful as they’ve tried to be in planning the day’s events, some folks just won’t be interested or ready to join in right now. “I hope that people feel supported, I hope that people are able to take comfort and participate in what they can,” she said. And even if they can’t, “I definitely want people to know that if they need help, or they need service, they can contact us anytime.”

The band’s plans

Though the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band won’t play in Highland Park this July 4, Lippitz felt strongly that the group should play somewhere that day.

Most years, the band plays at two parades on July 4. This year Lippitz has signed them up to perform at three: the 10 a.m. in Lake Bluff, the 12 p.m. in Skokie, and the 2 p.m. in Evanston.

“The purpose of this music has always been to push back against the darkness,” Lippitz said. “This is our joy, and this is our spirit, and this is our ruach, and let’s dance.”

And yes, their classic opener, “Freylekhs fun der khupe,” which they never got to finish playing last year, is in the lineup. “We’ll lead off with that,” Lippitz said. “Nothing gets cursed here. We reclaim it.”

But it’s not always easy to return and reclaim. A month after the shooting, Legg, trombonist, played a parade with a German oompah band. “I was OK, but I spent an awful lot of time looking at the crowd” and scanning rooftops, he said. “It wasn’t comfortable. But once it was over, I felt much better.”

One of his bandmates, a clarinetist who was on the truck last year, is done with parades. “He has no desire to do it again,” Legg said. “So everybody’s affected a little differently.”

Prager hasn’t played another parade yet since Highland Park. Upon hearing this year’s itinerary, his first thought — as a tuba player who’s always considered July 4 to be his big day — was that he’d love to play. “There’ll be hugs and laughter and playing and tootling around,” he said. Then he realized that he won’t be fully able to lose himself in the music.

“I wonder as the truck starts driving and gets into the parade and we start our first song, what will I be thinking about at that moment?” he said, his voice cracking. “Thank God that I’m here to play and to bring joy to people.” Several spots higher up in the parade order last year, his fate that day might have been different.

Nearly 12 months on, people are still asking themselves impossible questions. What if they had picked a different spot on the route? What if they hadn’t been able to run? Many of them aren’t quite prepared to see the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band perched atop its flatbed festooned in red, white, and blue — or any other floats — rolling along Central Avenue again.

Lippitz said the band can wait for that July 4 in the future when Highland Park is ready for another parade.

“When they decide that it’s time, we’ll be there,” she said.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO