Why did Israel kill more than 2,000 dogs in 2022?

Israel shoots thousands of stray dogs every year, many of them in the West Bank. The official reason is to prevent cases of rabies, but reducing their numbers appears to be the real goal

Stray dogs in the Galilee, northern Israel. (Photo: Yaron Kaminsky)

This article originally appeared on Haaretz, and was reprinted here with permission. Sign up here to get Haaretz’s free Daily Brief newsletter delivered to your inbox.

As Israelis were still digesting the election results last November, social media erupted over a series of shocking videos shot in and around the West Bank city of Hebron. The upsetting scenes included a dog screeching in pain after being shot by a youth with a hunting rifle; a group of youngsters viciously beating a dog with sticks; and a truck filled with dead dogs. These appalling sights came after Hebron Mayor Tayseer Abu Sneineh posted a video in which he urged locals to kill stray dogs and promised to pay 20 shekels ($5.50) for each canine corpse.

“It was meant as a joke,” Abu Sneineh claimed the next day. “I did it to provoke the animal rights organizations so they would do their job and take care of the dangerous phenomenon of stray dogs,” he explained.

The Israeli mainstream media highlighted the fact that the mayor issued this clarification following Israeli pressure on Palestinian Authority officials, including Maj. Gen. Ghasan Alyan, the coordinator of government activities in the territories (COGAT).

The Israel Defense Forces and COGAT declined to comment on the matter, but an Israeli officer confirmed the story. “We couldn’t just stand by,” he said. “I’m certain that if we hadn’t pressed them about this, we would have witnessed the killing of hundreds of dogs, maybe more. Israel prevented a massacre here,” he said with some pride.

However, a Haaretz investigation finds that, at the same time, Israel itself has systematically been shooting stray dogs.

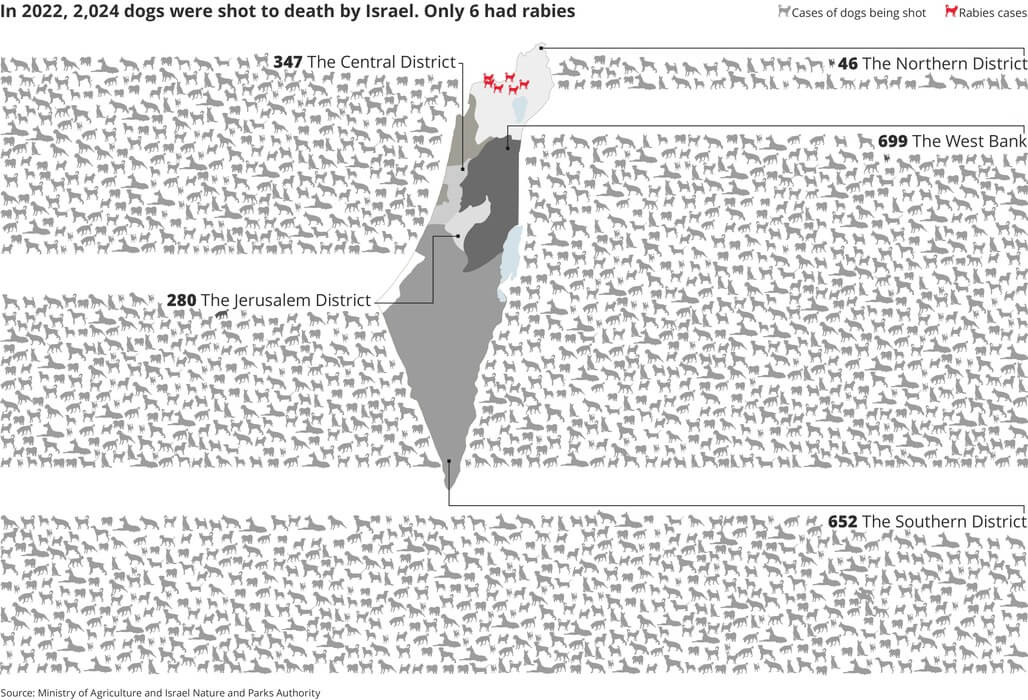

In the past year, the authorities culled 2,024 stray dogs: 797 were shot to death by inspectors from the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, 53 were shot by inspectors from the Agriculture Ministry’s Plant and Animal Inspection Unit, and a further 1,174 were shot with poisoned darts fired by veterinarians from the local authorities. (These figures do not include the thousands of dogs that were put to sleep in the kennels operated by local authorities and in the shelters of some animal protection organizations.)

The declared purpose of killing the stray dogs is to prevent outbreaks of rabies, with the authorities authorized to shoot and kill dogs suspected of being rabies carriers. Yet, in all of 2022, only six cases of rabies in dogs were diagnosed in Israel. Furthermore, the geographical distribution of the cases indicates that there is no connection between these cases and the areas where dogs are being shot.

All six rabies cases were found in northern Israel and 46 dogs in this district were shot to death. Meanwhile, 652 dogs were shot to death in the south, 347 in the center and 699 in the West Bank.

“It’s clear to all involved that rabies has nothing to do with it,” says Yael Arkin, CEO of the Let the Animals Live nonprofit. She claims the authorities use the rabies matter as an excuse to hide the real problem – the proliferation of stray dogs.

A 2017 joint study by her nonprofit and Humane Society International counted 32,820 stray dogs in Israel, with some 60 percent found in southern Israel. No more surveys of this kind have been conducted since then, but Arkin is quite certain that the number has only grown in the meantime. “Stray dogs are a problem – for people, for wildlife, for the dogs themselves,” she says. “But instead of dealing with the problem in a thoughtful way, the state is choosing the easy way out and just killing them.”

Wild West

The Nature and Parks Authority doesn’t hide the fact that the only action it is taking to deal with the stray dog problem is to kill dogs. Its protocols for shooting stray dogs does not require that evidence first be presented of attempts to address the problem by alternative methods (such as capturing the dogs and placing them in kennels operated by local authorities). In fact, the inspectors are not required to obtain any sort of permit from the Agriculture Ministry or the public veterinary service when killing a stray dog and need only report to the local authority’s district director.

“This is an outrageous procedure because of how lightly it treats the matter of shooting animals,” says attorney Erez Wall, who specializes in animal rights and works with Let the Animals Live. “Even though it’s called the ‘procedure for the treatment of dogs,’ it offers only one ‘treatment’: a death sentence for dogs.”

Wall explains that although the legal pretext used for shooting dogs is the rabies order, Nature and Parks Authority inspectors do not usually bring in the corpses of the dogs for examination to check if they are indeed infected. Instead, as four separate veterinarians with the public veterinary service tell Haaretz the inspectors simply leave the dead dogs to rot. “The authority previously admitted to us that they just leave the vast majority of corpses in the field,” he says. “And this happens despite the professional consensus that sanitation and collecting the corpses is of vital importance for preventing the transmission of diseases – including rabies.”

Leaving the corpses in the field also “creates food for other predators,” says zoologist Dr. Dror Ben-Ami. “Paradoxically, this creates a situation in which the inspectors shoot to keep stray dogs away from a certain area, and actually attract other animals like gazelles and also other stray dogs.”

The original Nature and Parks Authority protocol only permits its inspectors to shoot stray dogs within official nature reserves and national parks, or in a strip of area of up to 500 meters (1,640 feet) around them. In 2017, then-Environmental Protection Minister Zeev Elkin and then-Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel approved an addendum to the protocol, expanding the permitted shooting zone to all open areas.

This move, which was advanced following heavy pressure from the parks authority, led to a sharp 268-percent increase in the number of dogs that were shot to death by the authority’s inspectors – from 335 in 2017 to 1,233 the following year. Following efforts by animal rights groups, then-Environmental Protection Minister Gila Gamliel revoked the addendum in November 2020, and the number of stray dogs shot by the NPA’s inspectors fell to just 250 in 2021.

But the Wild West of the West Bank has its own rules. There, Israeli inspectors are allowed to kill stray dogs in open areas without hindrance. In the past year, the territories became the main area of activity for the authority’s inspectors: in Israel itself they shot to death 98 dogs, compared to 699 in the West Bank. The impetus is complaints from farmers on settlements about crop damage caused by the stray dogs, many of which come from PA areas.

“If they went around shooting dogs this way in Tel Aviv, there would have been a huge protest. But because it’s the West Bank, no one cares. The inspectors can do whatever they want and just shoot at them as if they were picking them off in a firing range,” says an Agriculture Ministry source. “They roam around with hunting rifles and feel like they’re the sheriff in town. The ease with which they shoot the dogs should trouble any human being, not just animal lovers. I won’t be surprised if the number doubles or even triples this year,” the source adds.

He says that because some of the inspectors are not skilled shooters, often the dogs’ injuries are not lethal and instead cause them great suffering. “In many cases, the inspectors don’t manage to kill the dog with the first shot, so they fire again and again while the dog is howling in pain. Other times, they shoot and strike the dog in the legs and leave it to bleed to death in the field. Anyone who has ever heard the howls of a dog dying in agony will never forget it.”

In response to a query from Haaretz, the IDF says that Maj. Gen. Yehuda Fuchs, the head of the Central Command that permits the killings in coordination with the Civil Administration, has begun to reexamine the protocol for shooting stray dogs in the West Bank, along with the injunction expanding the shooting zone to all open areas in the region.

Prolonged agony

Unlike the parks authority inspectors who use only guns and bullets, veterinarians from the local authorities – who are responsible for reducing the number of stray dogs in their respective areas – are only authorized to use poisoned darts. This is meant to be seen as a more humane method, but it actually causes the dogs much agony.

Veterinarian Dr. Yuval Samuel explains that the darts contain succinylcholine, which affects the nervous system and blocks receptors that control motor function. “The toxin causes all of the dog’s muscles to contract. It suffers intense pain until it finally suffocates and dies,” he says.

Samuel says that when poisoned darts are used, the location of the shot has a major effect on how much the dog suffers as a result. “If you strike the central mass, the dog will die within minutes. However, if you hit him in the leg, he’ll suffer for hours until he dies. I once had a dog brought to me who’d been seriously injured by a poisoned dart, fired by a veterinarian, that penetrated the pericardium. The dart didn’t kill the dog, but it was in excruciating pain. We had to do emergency surgery in order to save it. Over the years, we’ve had dozens of dogs that were brought into us after being terribly hurt by these darts. No one should have any doubt: the use of poisoned darts is abuse.”

At present, a veterinarian who wishes to obtain a permit to use poisoned darts must submit an application to the district veterinary office for initial approval. If it passes that stage, it then proceeds to the Veterinary Services Administration for final approval. Theoretically, the Agriculture Ministry procedures state that “the use of poison shall be permitted after all reasonable attempts have been made to address the problem of stray animals, and the administration has considered all the risks and is persuaded that there are no other means aside from poisoning with which to address the problem.”

But what often happens is that these veterinarians receive a permit to use poisoned darts without having proved that attempts were made to capture the dogs and transfer them to kennels for potential adoption.

For instance, an application for the use of poisoned darts that was submitted by the Rahat municipality in late 2021 was approved by the Veterinary Services Administration in the Agriculture Ministry, even though the municipality had no correspondence with any local authority kennels and presented no proof of any effort to capture the dogs during that year. Like many applications of this kind, this one did not mention any concern about rabies – only that the shootings were intended to “cull the population of stray dogs.”

Rahat is not the only Arab local authority where there is no kennel operated by the municipality. Of the 43 kennels operated by local authorities in Israel, not one is located in an Arab municipality. Some Arab communities, such as Umm al-Fahm, maintain connections with kennels located in Jewish communities. However, these are often located quite far away, making it hard for Arab veterinarians to transfer the dogs there.

“In the areas of depressed socioeconomic status – and in the Arab communities in particular – the stray dog problem is more common,” says attorney Wall. “In part, this is a consequence of years of neglect regarding animals as well as things like sanitation and cleaning. In the Arab towns, where there are no facilities to keep dogs and hardly any positions for municipal veterinarians, the Agriculture Ministry and the local authorities have a much greater tendency to turn to shooting. The ministry doesn’t offer other solutions and, unfortunately, this ‘solution’ is convenient for the veterinary services to approve.”

Indeed, according to data collected by the Agricultural Ministry for the first time (at Haaretz’s request), of the 1,174 dogs that were culled in the past year by poisoned dart, 816 were shot in Arab localities.

“We have no choice but to shoot them,” says a veterinarian, who wished to remain anonymous, at one Arab locality in the south. “The government doesn’t invest enough funding in this and we don’t have the ability to divert funding from other places for the sake of the dogs. Ultimately, there’s a problem here of stray dogs that could bite children and old people, and no one cares. I wish I could build a kennel here that could be a home for hundreds of dogs. However, without a budget for that and as long as the government continues to ignore us, we’ll continue with the available and cheaper solution: shooting.”

Public veterinarians who wish to obtain permission to kill stray dogs can also apply to the Agriculture Ministry’s Plant and Animal Inspection Unit for authorization to shoot the dogs with actual bullets rather than darts. But three veterinarians tell Haaretz that they have asked the ministry numerous times to send people from the unit, but were turned down. Therefore they had to resort to the poisoned darts, they say, adding that this was why the number of dogs shot to death by the unit this year was relatively low, at 53.

The ministry says the choice of whether to use bullets or poisoned darts relates to the area itself, since live fire is prohibited in urban spaces. However, the veterinarians insist that on many occasions they contacted the ministry about stray dogs in areas where live fire is permitted, but no one from the unit would come.

Temporary solution

Many researchers believe that shooting stray dogs doesn’t actually reduce their overall numbers and only serves as a temporary solution to a nuisance that is troubling the authorities at any given time.

“It can be categorically stated that shooting does not reduce the population of stray dogs,” says zoologist Ben-Ami, who earlier in his professional career examined the impact of shootings on Australia’s kangaroo population. “Even though they shot millions of kangaroos there every year, the population did not shrink,” he says. “As a result, and from examining other cases of systematic shooting of animals, we found that very often, shooting does not provide the solution.”

The reason, Ben-Ami says, is that with animals that have a high birth rate, such as stray dogs, it is very difficult to kill enough each year to maintain pace with the population’s reproduction. “With animals like dogs, if it isn’t done on a vast scale of 70 to 80 percent of the population, which is not feasible, you won’t be able to overcome the growth rate, so the shooting has a minimal impact.”

Samuel says that studies show that not only does shooting fail to cull the dog population, it can often contribute to increasing it. “Animals that live under stress of extinction due to the sound of gunfire reproduce at a younger age and produce more young. So, in an area where shooting is done, the population ends up growing,” says Dr. Moshe Rafaelovich, chief veterinarian for the Greater Tel Aviv region. He adds that killing dogs this way leads to the creation of a vacuum in that habitat, which is then filled by younger and more fertile dogs that reproduce at a faster rate.

“Contrary to what you might think, this cruel way of killing not only fails to solve the problem – it exacerbates it,” says Ben-Ami. “In this situation, one has to ask whether there is any justification for choosing such an old-fashioned and pitiless method. All the more so when there are better solutions that have been successfully tried elsewhere in the world.”

One of those is called CNVR (Collect, Neuter, Vaccinate and Return). This process has been successfully implemented in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Romania and other countries. The dogs are also given a medical examination before the spaying or neutering, and after vaccination they are tagged to ensure they are not collected for this process again in the future. “I personally know the team that carried out this method in Rajasthan,” says Ben-Ami. “They went from city to city and collected, neutered, vaccinated and tagged the dogs. The program was a huge success. And if they can do it India, then we can certainly do it in Israel too.”

Last year, lawmakers Yasmin Fridman, Sharren Haskel, Yorai Lahav-Hertzanu and Alon Tal submitted a bill to amend the law regulating inspection of dogs to promote the use of the CNVR method instead. However, the bill was not brought for a first vote in the Knesset. “In the discussions on the matter in the Education Committee, there was a sense that the bureaucrats from the Agriculture Ministry were doing their utmost to block a bill that proposed another tool for dealing with a problem that everyone agrees exists,” says Let the Animals Live’s Arkin.

Rafaelovich says Agriculture Ministry officials opposed the bill on the grounds that it contradicted a section of the law that says a person who possesses a dog cannot simply release it and abandon it. “In principle this is correct, but here we’re not talking about someone who sets their dog free in the wild but about dogs that already live in the wild,” he says. “The idea is to remove them momentarily, neuter and vaccinate them, and then return them to the wild – so that they cannot transmit rabies or reproduce. And in many cases, they will also become less aggressive. It’s obvious to any reasonable person that there’s no abandonment here.”

Following the ministry’s objections, the bill’s authors added a clarification that this aspect of the law would not apply to those who caught dogs and freed them as part of a CNVR program. However, the Agriculture Ministry remained adamantly opposed and worked to thwart the proposed legislation. Rafaelovich says that ministry officials asked who would be held responsible if dogs that were caught and returned to the wild as part of the program subsequently attacked someone.

“The ministry wanted to place the responsibility on the organizations or the people who would perform the operations – which is absurd since these dogs are anyway found in the wild, under the responsibility of the Agriculture Ministry, which is just trying to relieve itself of this responsibility,” he adds.

The Association of Local Authority Veterinarians also opposed the bill and published social media posts calling it “insane.” It warned of the “advent of rabies” and insisted that “this madness must be stopped.” Dr. Avi Sarfati, the group’s chairman, argued in the Knesset committee hearings that the proposal would not improve the stray dog problem, which he termed “a fiasco.” He maintained that having local authority veterinarians release the dogs into the wild after neutering and vaccination would create a conflict of interest for them. “Their job is to prevent strays; they cannot do this,” he said. Sarfati is also said to have warned local authority veterinarians not to support the legislation.

“They chose to use intimidation tactics reminiscent of a propaganda minister from a sinister regime in the previous century,” says Dr. Hilik Marom, a former chairman of the Israel Companion Animal Veterinary Association who was present at the Knesset Education Committee hearings. “At a certain point in the hearings, it just dawned on me: the local authority veterinarians are scared to death because if there will be no stray dogs, they won’t have any work,” charges Marom. “The realization that the system knows there are other, more humane solutions but refuses to support them really upset me.”

Marom says the arguments presented by the plan’s opponents were baseless. “They claimed that stray dogs attack people, but the truth is that the ones who attack are herding dogs or dogs that people own. Stray dogs, like all other wildlife, actually flee from people,” he says.

“We tried to get the Agriculture Ministry and the Nature and Parks Authority to provide figures that would support their claims, but we were not given any straight answers. The truth is that only after we’re able to conduct an experiment by trying the program and examining the data from it will we be able to know if it’s working or not. Science is based on data and observation, not on sowing fear and touting slogans.”

Rafaelovich is also an enthusiastic supporter of the CNVR method. “Since the country’s founding, we’ve been slaughtering stray dogs in all kinds of ways, but their numbers just keep growing. It’s time for Agriculture Ministry officials to stop clinging to such an outdated and immoral approach, and to advance the implementation of this program, even just as a pilot, as has been proposed. It’s a shame that the legislation did not pass because of petty objections. Ultimately, the stray dogs are the ones who will pay the price – they already live in miserable conditions and are often killed with terrible cruelty.”

Soul-searching

Another possible solution is to catch stray dogs and transfer them to kennels for potential adoption. But in the past two years, there has been a significant drop in the number of dog adoptions in Israel – both from local authority kennels and nonprofit organization kennels – along with a sharp increase in the number of dogs that are sold each year.

As reported recently in Haaretz, over the past three years the sale of pseudo-pedigree dogs has soared by tens of percentage points, and the industry is estimated to have had a turnover of more than 100 million shekels in the past year, almost all in cash and under the table. An estimated 20,000 such dogs were sold in the past year as part of an unsupervised and unauthorized breeding industry, in which the animals are often kept in terrible conditions.

“The kennels and shelters are more packed than they’ve ever been,” says Arkin. “People would rather spend thousands of shekels on a dog, and don’t even think about adopting a dog that is yearning for a warm home.”

She says that in order to reduce the population of stray dogs, dog sales in Israel also need to be significantly reduced – in part by banning the import of dogs and by imposing a tax on the buying and selling of dogs.

Arkin also suggests that the two solutions could be combined to deal with the problem even more effectively. “As part of the CNVR process, dogs could be evaluated for their suitability for adoption so that the friendlier dogs are placed for adoption, while those that are less suitable are returned to the wild after being neutered and vaccinated.”

Ben-Ami notes that the solutions could also be tailored in accordance with the different ecosystems in different parts of the country. So, in areas with an ecological imbalance, such as the Jerusalem Hills, preference would be given to transferring dogs for adoption. Meanwhile, in areas where the ecosystem is more balanced, the dogs would be returned to the wild without fear of their harming other wildlife.

However, until such steps are put into effect, thousands of dogs will continue to pay with their lives. “The way in which Israel currently chooses to deal with the problem is just totally immoral,” says Ben-Ami. “The fact that the dogs suffer in so many cases, whether as a result of errant shooting or as a result of the use of poisoned darts, is absolutely infuriating. I would expect our society to show more compassion.”

Arkin points an accusing finger at the state, “because it does not ban the killing of dogs and does not advance more moral solutions for dealing with stray dogs. However, the public also bears some responsibility. Each person who decides to buy a dog instead of adopting one needs to recognize that they are sending another dog to its death – often to an agonizing death. I think that every such person needs to look themselves in the mirror and do some soul-searching. This is not the way that people who genuinely love dogs act.”

Responses

In response to this report, the Nature and Parks Authority responded that “it acts in accordance with the rabies law in regard to stray dogs. The activity is conducted in accordance with the law, with the aim of reducing the spread of rabies to wildlife. And in the West Bank, all of this activity is in accordance with the military injunction. The phenomenon of stray dogs in the West Bank is widespread due to a lack of sanitation. In 2022, an agricultural damage inspector began operating in the Judea and Samaria district to assist farmers in dealing with agricultural damage and in dealing with stray dogs, as in other parts of the country.” As for the claim that the authority does not remove dead dogs from the wild, the authority says it does so only when rabies is suspected. However, it declined to provide any data on the number of dead dogs that have been removed.

The IDF, meanwhile, says that “the treatment of stray dogs in the West Bank is done by inspectors from the Civil Administration that were authorized and trained for this in accordance with the law that applied in the area before the entry of IDF forces, and within the jurisdiction of the Israeli regional councils according to injunctions from the military command. In accordance with the relevant law and procedures, shooting is only done as a last resort, when it is not possible to capture an animal that is strongly suspected of being a rabies carrier, and the animal has no owner. The number of dogs that were shot in the West Bank in 2022 derives from the large number of stray dogs in the area with no owners.”

The army also acknowledges that no efforts are made to capture the dogs and transfer them to kennels operated by the local authorities.

The Association of Local Authority Veterinarians said in response: “The organization expressed its opposition to the [abandoned dogs] bill for a number of completely professional reasons. The bill as it was presented, and despite attempts and dialogue with lawmakers to insert the necessary professional changes, could cause serious harm to Israelis’ security, spread disease and create many ecological hazards, including harming of the dogs themselves – and this is not acceptable in an advanced country like Israel. The organization expressed its view in all the standard ways, including social media, in light of the severity of the situation and the bill’s authors’ ignoring the professional opinions of all the officials in the committee hearings.”

The Agriculture Ministry responded that “according to the professional view of the Veterinary Services, returning dogs to the wild after vaccination and neutering is akin to abandoning them to natural hazards and to disease, and could also negatively impact public safety and health, as well as protected values of nature. Because of this, in recent years the Agriculture Ministry has invested millions of shekels to assist the local authorities in fulfilling their responsibility to address the problem of stray dogs while promoting responsible adoption. Each year, 2,500 stray dogs are collected by the local authorities, given medical treatment, neutered or spayed, and put up for adoption. Incentives are also given to the stronger municipalities to aid the weaker ones, particularly in Arab and Bedouin society, in taking action to address the issue. The Agriculture Ministry director general is currently considering a pilot plan to accelerate the handling of animal welfare issues, particularly the issue of stray dogs.”

It adds: “The use of poisoned darts is done subject to the approval of the Veterinary Services, after they have thoroughly examined the application and ascertained that the local authority exhausted all other alternatives. Only after this process, and under the guidance of the Veterinary Services, does the ministry’s unit assist the local authorities in carrying out the action.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO