Did everyone miss an antisemitic campus murder?

The killing of an Arizona professor on Yom Kippur raises questions about how the Jewish community should respond to danger

A memorial for University of Arizona professor Thomas Meixner on Oct. 14, 2022. Murad Dervish, a former graduate student who believed Meixner was leading a Jewish conspiracy against him, has been charged with killing the professor. But a variety of factors have made members of the local Jewish community reluctant to view antisemitism as the primary motive. Photo by University of Arizona

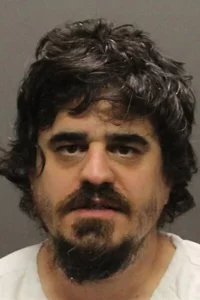

Here are some facts. On Yom Kippur, a former University of Arizona graduate student named Murad Dervish stormed into the earth sciences building on campus. Dervish believed Thomas Meixner, the hydrology department head, was leading a Jewish conspiracy against him. “Kikes should not be allowed to exist anywhere, ever,” Dervish had previously told one faculty member. Dervish allegedly shot and killed Meixner. It was the only such murder in 2022, a year full of antisemitism. It escaped widespread attention until after Thanksgiving.

But there are other facts, too. Meixner wasn’t Jewish. Dervish’s original grievance was over a bad grade. The 46-year-old had a long history of violence, including against his parents, and scared some faculty to the point they had avoided campus. His antisemitism didn’t become public until weeks after the murder, when it was revealed alongside a tirade against Asians. And the national spotlight that Jewish groups eventually shined on the Tucson school? Some local Jews say it made things worse.

Many outside the region came to see the murder of Meixner, a beloved teacher and father of four, as a blatant act of antisemitism. It landed on the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s list of worst antisemitic incidents of the year, and was widely covered by Jewish media in the United States and Israel. It required — and received — a Jewish response. Yet many Jews on campus saw something more layered and grew frustrated when outsiders began to publicize the case without acknowledging its complexity.

Abigail Simon, a Jewish engineering student, noted that the story went national at a time when Jews are increasingly nervous about antisemitism on campus, and surmised that they might draw conclusions about fresh incidents without much thought.

“I hate to make it seem like people were jumping on a bandwagon,” Simon said. “But I think it was just another drop in the bucket that, ‘Oh, there was a murder on campus,’ and, ‘Oh, the shooter was antisemitic.’”

Though Dervish’s antisemitism, and the location of the shooting, across the street from Hillel, prompted a rapid and thorough response from Tuscon’s Jewish community, their efforts drew little attention as the news of the murder spread. Local Jews also understood that the part of the tragedy that most upset faculty and students was that Meixner and others had repeatedly warned school officials that Dervish posed a threat and they had failed to act. Focusing on antisemitism, some feared, might overstate the role it played in Meixner’s death, and present Jews as more endangered than they actually were.

Outside Jewish groups that tried to draw attention to the case countered that there was nothing subtle about Dervish’s bigotry — no matter what role other factors played in his violence — and point out that antisemitism can operate in strange ways: Its victims often aren’t Jewish.

A grand jury indicted Dervish on seven charges, including first-degree murder, in October. Dervish has pleaded not guilty and his trial is scheduled for September. Judge Howard Fell declined his attorney’s request to ban media from the courtroom.

“Justice grows the best in the full light of day,” Fell said.

A murder, and a revelation

When the shooting first took place, Simon and other students gathered at the campus Hillel for High Holiday programming only knew that something very bad had happened. The scream of police sirens had interrupted a text study. And, a different student recalled, what seemed like the entire campus police department came to a screeching halt outside the academic building across the street.

It turned out that the police had responded too late, allowing Dervish to escape. Hillel went into lockdown. Simon remembered feeling grateful that Hillel had hired armed security guards for the High Holidays. Everyone gathered in the lounge. “We were all sitting in this one room trying to act like things were normal, but obviously nothing was,” said Jordyn Morris, another student present that day.

Dervish was arrested several hours later on a highway outside of Tucson with knives, machetes, guns and extra ammunition. Another bombshell would come two weeks later, when a local newspaper columnist published an interview with Eyad Atallah, a lecturer in the hydrology department, who — the headline said — “prepared to be shot on campus and barely avoided it.”

Tim Steller, the Arizona Daily Star columnist, revealed that Atallah and other faculty members had been hounded for months by Dervish, who was convinced that a bad grade he received was the result of a Jewish conspiracy against him.

“As Arabs we’re supposed to stick together and I trusted you, and instead you’re a filthy kike lover,” Dervish had texted Atallah last winter.

It wasn’t the point of his article, but based on those messages, Steller was the first to suggest that Meixner’s murder was driven by bigotry against Jews. “Although Meixner was Catholic, his killing could be considered an antisemitic attack,” Steller wrote on Oct. 22.

The column emphasized that university officials were aware of the threats. They had expelled Dervish and banned him from campus, but he kept returning with impunity. And nobody thought to tell Jewish leaders on campus, or in Tucson, that a man who had menaced faculty — to the point several had started working from home out of fear — was blaming his problems on Jews.

After the column was published, Jessica McCormick, director of the campus Hillel, emailed Robert Robbins, the university president. Why, McCormick asked, had the administration failed to notify Hillel of Dervish’s antisemitic comments? Why hadn’t law enforcement protected the Hillel building while Dervish was on the loose? Why hadn’t any school officials reached out after the shooting?

McCormick forwarded her email to the Hillel community. “Tochechah, or rebuke, is an important concept in Judaism,” McCormick wrote on Oct. 24, explaining why she had reached out to the administration. Her note was how many Jewish students found out about Dervish’s antisemitic motives. The revelation rattled some of them deeply.

Rachel Borrego, a junior, had already been plenty scared on the day of the shooting. She sat next to an exit for at least an hour — ready to bolt if the shooter arrived. Now, it was as if her worst fears had been confirmed.

“I was across the street from someone who had murdered someone, was armed, and violently antisemitic,” Borrego said. “At any point he could have just looked over at Hillel and thought, ‘Hey, I’m already here — I’m already at this point — why not go out with a bang?’”

In her email to Robbins, McCormick invoked the Jewish value of pikuach nefesh, or sanctity of life. “We strongly believe the value of pikuach nefesh is shared between the university and our Hillel,” she wrote. McCormick was pleased to hear back almost immediately, and school officials met with her and a small group of other Jewish community representatives four days later.

The university apologized and agreed to everything McCormick requested. A joint statement from the school and Hillel on Nov. 11 announced that a new advisory council on Jewish life and antisemitism would be formed with eight goals, including integrating communication between campus police and Hillel, and training officers on how to address antisemitism. It would also examine issues unrelated to safety, like increasing kosher food access.

The university’s response to Jewish concerns seemed to be one of the only tidy resolutions amid a mounting furor from students and faculty, who felt the school had grossly failed to protect them, and community frustration with the local prosecutors who had declined to press charges against Dervish for threats made before the shooting.

“It’s very hard to say in the wake of a man’s murder that you’re pleased about anything,” McCormick said in an interview. “But I feel like important and productive change is now being made.”

Weeks later, a new spotlight

The restored calm was short lived. On Nov. 22, the Arizona Republic, the state’s largest newspaper, based two hours north in Phoenix, published an opinion piece: “UA professor is dead because no one took antisemitic threats seriously enough.”

It was written by Michael Masters, director of the Secure Community Network, the national group focused on protecting Jewish institutions from vandalism and violence. The group had monitored the shooting since it took place. In the weeks that followed, antisemitic outbursts from Kanye West and other high-profile incidents of antisemitism put Jews on edge. But the October shooting stuck with Masters. He wanted to offer advice on how to prevent similar tragedies and make sure it wasn’t swept under the rug.

“I, myself, was surprised about the lack of awareness around this incident,” Masters said in an interview. “I think that says something about where we are, as a society, that something like this doesn’t even rise to the level where it’s getting the proper attention.”

While Masters’ piece, the first to focus primarily on Dervish’s antisemitism, largely discussed practical steps the University of Arizona and local law enforcement could have taken to prevent the murder, Masters was unsparing in his conclusion: “Professor Thomas Meixner lost his life because antisemitism is not being taken seriously enough.”

The piece prompted a new flurry of coverage, nearly two months after Dervish had pulled the trigger. JTA and JNS articles based on Masters’ account ran in Jewish newspapers across the United States and Israel. A few days later, Jewish On Campus, an organization that publicizes incidents of antisemitism at colleges and universities, summarized Masters’ account to its 41,000 Instagram followers.

“When we say antisemitism kills, we mean it,” the group posted on Instagram, alongside a darkened photo of the University of Arizona’s campus.

The attention caught the local Jewish community off guard. The Secure Community Network works closely with Hillel International. But McCormick said “they were fully operating on their own track,” and she had no advance notice of the Masters’ article. She was disappointed that it didn’t include any reference to the agreement reached with university officials weeks earlier.

“I would have loved for that to be a blip in the piece,” she said.

While online searches about the case had previously been concentrated in Arizona, Google Trends data shows that immediately after national Jewish organizations began discussing the story, interest surged in states across the country.

As the story spread in November and December, McCormick was inundated with phone calls from people around the country expressing both support and alarm. Students like Morris, who had been at Hillel on the day of the shooting, suddenly started seeing friends outside Arizona posting about her school on social media. Family from back home in Texas texted her about it. The attention was bewildering.

Morris said the Jewish community on campus had already processed what took place. Hillel had met with school officials. There was a plan in place to hopefully prevent anything like this from happening again. But none of that was clear from the Arizona Republic article or what Jewish on Campus posted.

“A lot of people were contacting the university basically to yell at them — like, ‘Why didn’t you do anything sooner?’” Morris said. “In a certain way, it brought our community back to square one of the healing process.”

An antisemitic killing — or something else?

But even as it became clear that the university had failed to alert and protect the Jewish community from a violent antisemite, Dervish’s motive for killing Meixner seemed, ironically, more murky. Not everyone on campus was convinced that the professor’s murder was antisemitic.

Dervish had sent a lot of antisemitic messages to Atallah, and said that an online background check had led him to believe that Meixner, a devout Catholic, was Jewish. But he also believed the conspiracy against him was being organized by both Jews and Asians, and after he was expelled he unleashed a racist tirade against the school’s assistant dean of students, who didn’t appear to be either. Dervish had previously tried to kill both of his parents, his father told the Arizona Daily Star. And while attending San Diego State University, a female undergraduate student took out a restraining order against Dervish.

An independent investigation into the shooting commissioned by the faculty senate found that Dervish had sought to kill at least four faculty members in the hydrology department but could only locate Meixner, according to an interim report released in late January. There is no indication he believed the others were Jewish.

Dervish had been a volatile presence on campus since he enrolled at the school in the fall of 2021. He screamed obscenities at a professor in the middle of class, and after he lost his graduate assistant teaching job as a result, he sent threats that terrified hydrology faculty so much that they moved classes to Zoom. Expelled and banned from campus last February, he kept coming back, and accosted a professor at a nearby CVS. Dervish threatened an employee at the dean’s office: “I don’t think you have any clue who you are dealing with but you are about to find out and I really don’t think you’re going to like it,” he wrote. Meanwhile, he was sexually harassing a female undergraduate student — the same thing he was accused of in San Diego — contacting her more than 30 times.

Sometimes Dervish made his bigotry clear. “You don’t understand how Jews and Asians think and how they treat people,” he wrote in one message to a faculty member. “Somebody not very long ago invested a lot of resources to nearly eradicate them from the world.”

Judging from media reports, social media commentary and the faculty investigation, though, many in the community did not think the most egregious aspect of Meixner’s murder was Dervish’s antisemitism and racism. It was the apparent failure of university officials and law enforcement to stop a clear and present danger — to keep members of the community safe.

The student harassed by Dervish last March reported that a campus police officer offered her no help. “I said, ‘so you are not going to do anything until anyone gets killed, are you?’” she told the faculty committee. “And he just looked at me and said nothing.”

When Dervish showed up at the hydrology department on Oct. 5, people recognized him. One student called 911, another ran to a professor’s office where together they turned off the lights and barricaded the door. “I knew you were going to do this,” Meixner shouted after Dervish shot him, according to witnesses.

Yet when Paula Balafas, the university police chief, briefed the media after the shooting, she seemed oblivious to the widespread fear of Dervish in the hydrology department going back months.

“It’s just one of those things you can’t even predict,” she said. “Moving forward, if you see something, say something.”

The University of Arizona police department referred questions from the Forward to a school spokesperson, who sent a link to the university’s joint statement with Hillel and said the administration had hired an outside security firm to investigate the incident.

The university’s underwhelming response to concerns over Dervish, his long record of disturbing behavior, and the fact that those mourning Meixner have not focused on the issue of discrimination, have made many Jewish students on campus reluctant to see the murder primarily as a simple case of antisemitism.

“It just adds another layer to all of the other reasons that the shooting occurred,” Simon said. “The reality of the situation is, Dr. Meixner’s not Jewish and I feel personally that we should be focusing on his family and his community and just privately dealing with the university about the antisemitism.”

Kate Herreras-Zinman, a Jewish film major, said Dervish’s reported mental illness has shaped her view of the shooting. “I look at it as if some crazy person did a mass shooting and that’s unfortunately kind of commonplace,” she said. “On the other hand, it was still motivated because he felt that guy was Jewish.”

Context collapses

Dervish, of course, is hardly the first person to unleash his antisemitism against targets who weren’t Jewish. Many of the people identified on antisemitic flyers distributed by the Goyim Defense League, lists of Jews who supposedly control various industries are not, actually, Jewish. The 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, was ostensibly about protecting a Confederate monument, although the organizers were viciously antisemitic. And the white supremacist who killed 10 people at a Buffalo, New York, grocery store last year targeted African-Americans, despite a manifesto in which he focused his ire on Jews.

Jews often struggle to respond to such incidents in a way that recognizes the role antisemitism plays in these events, without taking attention away from the actual victims. “The situation was a lot more complex than could be fit into one Instagram post,” said Morris, a sophomore studying politics and music.

Amid the hundreds of comments on the Jewish On Campus Instagram post, University of Arizona students tried to inject context. “There are so many layers to what happened and how it affected the Jewish community,” Morris wrote. @HillelArizona also commented, pointing out that the university was working with them. The account was quickly assailed for not having posted about the murder.

“We heard people reaching out and saying it’s a shanda that you haven’t posted about this,” McCormick said. She had, in fact, posted about the incident several times, but all back in October when it had unfolded on campus.

At least two dozen new organizations have sprung up in recent years to fight antisemitism, often with a focus on college campuses. But Jewish students have sometimes felt left behind by the advocacy ostensibly done on their behalf. Leaders of the pro-Israel club at George Washington University said they were confused this fall after StopAntisemitism released a report card that said Jews felt unsafe at the school. Later that semester, Accuracy in Media drove a billboard truck featuring an image of Hitler around UC Berkeley’s campus in October that was meant to criticize anti-Zionist clubs on campus but ended up alarming Jewish students.

Julia Jassey, who runs Jewish on Campus, said that the organization aims to speak out against antisemitism while “bearing in mind the experiences on the ground with respect and caution.”

She said the murder was an example of how antisemitic conspiracy theories can lead to violence. “We offer our sincere condolences to both Professor Mexiner’s family and the University of Alabama community,” she said in an email, referring to the wrong school.

A distorted version of Meixner’s killing has started seeping into the Jewish discourse in the months since it first made national rounds. David Nirenberg, author of Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, wrote in a January op-ed for The Wall Street Journal that Meixner was murdered because Dervish thought he was “the Jewish leader of a Zionist plot against him,” though nothing suggests Dervish ever referenced Israel or Zionism. The Wiesenthal Center included Meixner’s death in its list of last year’s worst cases of antisemitism, saying only that he was killed because Dervish “mistakenly thought Meixner was Jewish.” That claim was also made by a newspaper in suburban Phoenix when they profiled a local rabbi.

There has also been a scattered backlash to these accounts. Michael Tracey, a contrarian political pundit, lambasted the Wiesenthal Center’s decision to include the murder on its list of top antisemitic incidents. Tracey told his 300,000 Twitter followers in January that the organization had ignored “mountains of countervailing evidence” in classifying Meixner’s death as a case of antisemitism. And a right-wing local news outlet, the AZ Free News, declared: “Jewish rights group falsely claims UArizona professor murdered due to antisemitism.”

Still, despite the difficulty of capturing the full context of local antisemitic incidents, like what happened in the case of Meixner, national organizations like Secure Community Network and Jewish on Campus sometimes feel that their distance from these events is helpful. Universities, concerned about their reputations, often downplay hate crimes, while local Hillels rarely want their schools to be known as dangerous places for Jewish students. At the University of Arizona, Jews were sensitive about taking the spotlight away from Meixner’s family — and focused on practical steps to prevent future tragedies.

Sometimes, Masters said, the simplest explanation is the correct one: Dervish made antisemitic threats, thought Meixner was a Jew orchestrating a Jewish conspiracy against him, “and Professor Meixner is now dead.”

“We seem to be lost in an academic discussion about motive,” Masters said. “The reality is that we need to take Murad Dervish at his word.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO