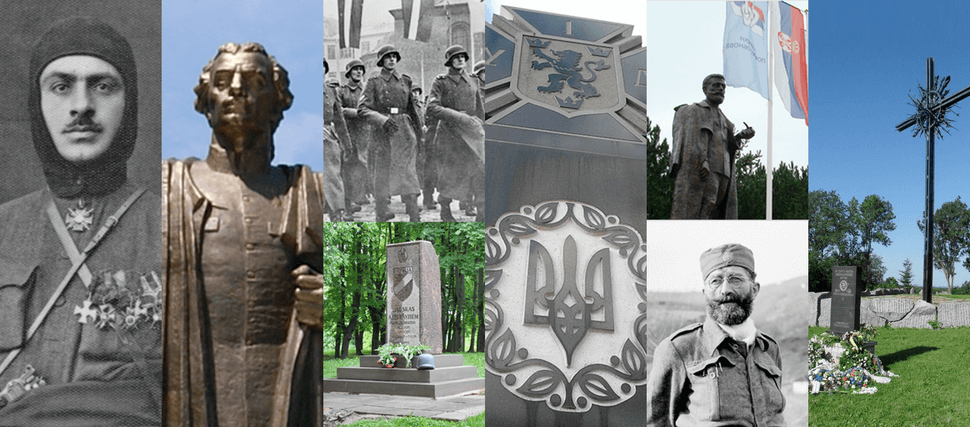

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, reflections on 2 years of documenting monuments to Nazi collaborators

For millions of people, especially in Europe, World War II never ended

Photo by The Forward

It’s been two years since the Forward published my initial investigation of streets and statues honoring Nazi collaborators around the world. On that International Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2021, we documented 320 such monuments in 16 countries on three continents.

They honored dictators like Hungary’s Miklós Horthy and Slovakia’s Josef Tiso, who deported hundreds of thousands of Jews to their deaths. In Melbourne, the investigation unearthed a bust of Croatian fascist Ante Pavelić, whose regime exterminated Jews, Serbs, and Roma. Most shockingly, the project exposed a monument to Latvian SS soldiers in the heart of Belgium.

We thought we were publishing a comprehensive accounting, complete with country by country lists. But we soon discovered we’d only scratched the surface — thanks to tips from researchers and readers, the project now has more than 1,652 instances of honoring collaborators in 30 countries across five continents.

This includes some three dozen in 16 U.S. states — Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia and Wisconsin — and, added just this week, new lists of monuments in Bulgaria and Argentina.

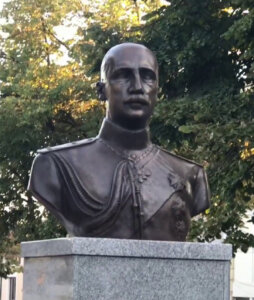

Bulgaria is a prime example of Holocaust whitewashing.

Its Czar Boris III, who ruled the country from 1918 until his death in 1943, has been honored — including with a memorial erected in Israel in the 1990s — because the country did not deport Jews in Bulgaria proper during the Holocaust. But Boris’ rule included the passage of laws that restricted the rights of Jews in the country, denied them citizenship and established quotas in some professions. His government also deported more than 11,300 Jews from territories under Bulgaria’s control; nearly all were murdered in Treblinka.

Israel decided in 2003 to take down the monument.

Incremental changes

Since we began this project, it’s been gratifying to see a handful of streets have been renamed and monuments removed.

Bucking intense pressure, a Belgian town removed a monument to Latvian soldiers in the military wing of the Nazi Party last summer. Around the same time, a Smithsonian-affiliated museum in Huntsville, Alabama, quietly took down a giant quotation from Werner von Braun, who was part of a group of Nazi scientists brought to the U.S. in a secret program after the war, and became a NASA leader known as the “father of space travel.”

I was inspired by people like Michael Samaras, who unearthed the dark past of Bob Sredersas, a Nazi collaborator who had fled to Australia, and successfully lobbied an art gallery there that had been endowed by Sredersas to remove his name. Similarly, a Holocaust survivor named David Salz fought to rename a school in Friedberg, Germany, that honored von Braun; Salz had been imprisoned at Auschwitz as well as Dora-Mittelbau, where von Braun used prisoners to build the deadly V-2 missile he had created.

Lessons learned

One thing I’ve learned in more than two-and-a-half years of doing this reporting is that, for millions of people, especially in Europe, it seems World War II never ended. I’m not talking about old veterans reminiscing of old trenches. I mean unfinished business that needs finishing.

The most obvious example is President Vladimir Putin of Russia, who falsely painted his invasion of Ukraine last Feb. 24 as aiming to stem the tide of fascism. The notion that all Ukrainians are Nazis is a slur, of course, but Putin’s use of it to justify his war is worth scrutiny.

Because he isn’t alone. Across swaths of Europe, old maps are unfurled as irredentist movements in places like Serbia and Hungary speak longingly of their countries’ formerly broader borders. And Holocaust revisionism and the honoring of Nazis and their collaborators is never far from the surface.

Earlier this month, an international row broke out after a brutal assault in the North Macedonian city of Ohrid. The victim was a secretary for a new cultural club honoring Boris III, the Bulgarian leader who collaborated with Hitler and had seized Macedonian territory in 1941.

Indeed, this project’s roots are not so much in history but current events. In the process of covering European far-right movements, I kept coming across campaigns to whitewash Nazi collaborators. Wherever I found angry men and torchlight marches, I also found statues of leaders and soldiers who helped Hitler fight the war and exterminate Jews.

I came to think that neo-Nazis in Europe are more obsessed with WWII history than far-right extremists here in the United States are with the Confederacy and the Civil War. This was during a period in which many American cities took down monuments to Confederate commanders.

When I saw that the Southern Poverty Law Center had a database and map tracking some 2,000 Confederate monuments across the country, I thought it was important to have something similar for Nazi collaborators, and brought the idea to the Forward.

Today’s neo-Nazis use these statues to obfuscate and distort history; I wanted to shine a light on them, in hopes of reminding people what really happened in the Holocaust.

What particularly stunned me is how even in many Western nations seeking to address legacies of slavery and colonialism, Nazis get a pass. In fact, as I wrote last year, even Germany, long seen as an international model for its reckoning with the Holocaust, has more than 150 places named for people with blood on their hands.

Some argue that taking down a statue honoring a Nazi collaborator or renaming a street is akin to “erasing history.” But that’s not really the case. Most of the monuments in our project were erected only in the past several decades.

As I sorted through thousands of statues, buildings, and streets, the only examples of actual historical objects I found were monuments to Benito Mussolini and Italy’s king Victor Emmanuel III that were created around the 1930s when Italy was a fascist state. Otherwise, the streets and statues glorifying Nazis and collaborators are reflective honors, not parts of history — these two things are too often conflated.

Others say that instead of toppling Nazi monuments, we should contextualize them. In other words, rather than remove a statue, put up a sign next to it saying the person was bad.

But instead of “neutralizing” the Nazi monument or street, such contextualization has the opposite effect. It sends the message that we know exactly who we’re honoring and we’re going to keep honoring them anyhow.

Because in the end, claiming to care about antisemitism and the Holocaust while putting up a statue to killers of Jews makes about as much sense as claiming to oppose Islamic terrorism while erecting a statue of Osama bin Laden — even if that statue comes with a board saying terrorism is bad.

You can read prior articles about Nazi monuments and browse through our country-by-country lists of them here. If you know of statues, streets or other items honoring collaborators that are not listed on our site, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO