Was this Jewish prayer book printed before the Gutenberg Bible?

Book dealer Moshe Rosenfeld says he has proof that a Jewish prayer book was printed in southern France in 1444

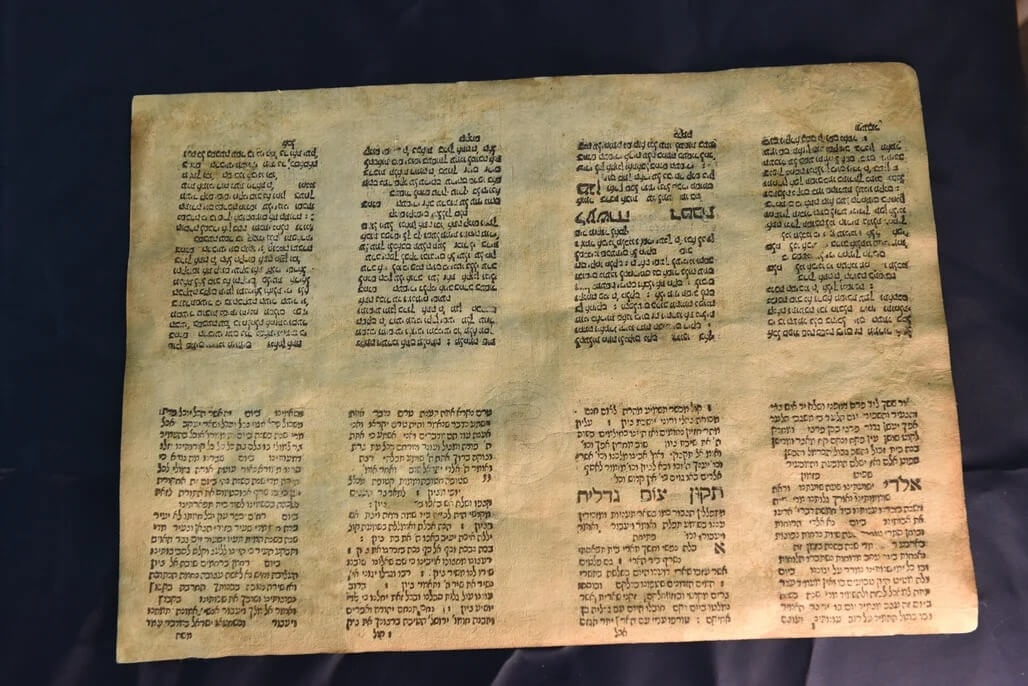

The pages of the Jewish prayer book that may date to 1444. Courtesy of Moshe Rosenfeld

This article originally appeared on Haaretz, and was reprinted here with permission. Sign up here to get Haaretz’s free Daily Brief newsletter delivered to your inbox.

“I’ve found the smoking gun,” says Moshe Rosenfeld, sitting in a work area filled with old manuscripts on the ground floor of a Jerusalem publishing house. He believes that the first printed book in the West is a siddur that includes piyyutim for Sukkot, published in a French publishing house in 1444. If he is right about his discovery, the history books will have to be rewritten in order to credit the Jewish people with a significant contribution to the development of mankind.

According to Rosenfeld, the book predates the invention attributed to Johannes Gutenberg – the printing press – by about a decade. “We have before us a world-embracing discovery, a revolution and a correction of a historical injustice,” he triumphantly declares. Now he just needs to convince the rest of the world.

The Jerusalem resident, a father of four and grandfather, researches and deals in ancient manuscripts. He is also the director of the Institute for Computerized Bibliography of the Jewish Book, a private company that has a database of over 100,000 ancient Hebrew books – dating from 1444 to 1948.

Two months ago, he presented his discovery at the annual gathering of the International Association of Paper Historians in Austria. “Have you come to cause a worldwide sensation?” asked his guests in anticipation. Rosenfeld says he would be satisfied with a more modest outcome: the book’s pages on display at the entrance to the National Library of Israel, which is currently under construction near the Knesset. “In my dreams, I see 50 spotlights trained on this book,” he smiles.

Huge diamond

In order to understand the roots of this story, we must go back several centuries. According to the official narrative, in the mid-15th century German inventor Gutenberg developed the world’s first printing press in the city of his birth, Mainz.

Until then, there were no books as we understand them – pages printed serially for broad distribution. Each book at the time was an independent creation, produced by manual labor that took months. There was also a very low literacy rate worldwide.

Nowadays, in the digital age, the process Gutenberg developed seems complicated and complex – because it was. He created numerous identical molds for each letter in the alphabet, initially from wood and later from lead and tin. These were the world’s first fonts. In order to transfer the letters to paper, he used a press. In 1455, he printed 180 copies of the Bible, thus paving the way for a revolution in human culture.

Anyone with any knowledge of the field will be aware that the Chinese invented printing long before Gutenberg. However, his status as the father of printing endures – one reason being that he did so in Europe.

Since the late 19th century, there have been scholars who questioned Gutenberg’s precedence on the Continent. One of them was Jewish historian Prof. Cecil (Bezalel) Roth, who as long as 60 years ago raised the possibility that the beginning of printing in Europe took place an entire decade earlier.

Rosenfeld claims he has absolute physical proof which, finally and decisively, confirms what was until now merely an assumption.

Our story begins in 2015, when a Jerusalem book dealer took apart the binding of an old book he had purchased. Inside, he found two old printed sheets of paper in excellent condition, which caught his eye. The dealer, who does not want to be identified by name, turned to Yitzhak Yudlov, a librarian and bibliographer who used to be a member of the Institute for Hebrew Bibliography and the National Library.

“You have a huge diamond of a Jewish book,” he told the dealer, adding that he believed these were sheets printed in the city of Avignon, southern France, between 1444 and 1446. Their existence had long been the subject of rumors, but had never been unearthed.

On the official stationery of the National and University Library (now the National Library of Israel), Yudlov wrote that he believed these pages were the last surviving remnants of an Avignon printing house run jointly by a Jew and a Christian, “about 10 years before Gutenberg.”

Surprisingly, despite the power of his words, no top-ranking academic scholar bothered to delve deeper into his pioneering conclusion.

The contents of the book are also interesting. They are part of a siddur (Jewish prayer book), which includes piyyutim for the fast days of the 17th of Tamuz, the Fast of Gedaliah, the 10th of Tevet, the ninth of Av – and hoshanot, which are recited on Sukkot.

The next chapter in our story takes place in 2018 in Rosenfeld’s small office in Jerusalem, where he worked at the time with the bibliographer, collector and publisher Yeshayahu Vinograd (who died in 2020). The Jerusalem book dealer sought their opinion on the pages of the book in his possession. The two men also determined, based on their technical and content-based examinations, that this was the earliest printed book in the Western world.

With these opinions in hand, the dealer sold the book to another party. However, when the buyer subsequently tried to sell it at auction, rumors began circulating that the pages were actually forgeries.

Since then, Rosenfeld has embarked on what seems his late-life’s mission: to do everything in his power to prove that the book is authentic.

First, he turned to the Institute of Forensic Science in Jerusalem, headed by forgery expert Avner Rosengarten. He examined the pages and determined in 2019 that he “saw no evidence of forgery.”

Armed with this opinion, Rosenfeld threatened to sue anyone who implied that the book is a forgery, including employees of the National Library and Wikipedia writers who were referring to it is “an invented story.” Writers at the online encyclopedia changed the entries “History of the Jewish Book,” “Hebrew Incunabula” and “Printing” to include comments slating Rosenfeld’s research, which he claimed justified a libel suit. “There were no bibliographical studies there that contradict our research but simply slander – and against someone they had never met,” he says.

He later traveled to Avignon, where he found about 20 documents from the years 1444 to 1446 in the local archive, These documented what he saw as the story behind the printing of “his” book. Part of the story was familiar to those in the know, but Rosenfeld was able to see with his own eyes the original documents capturing it.

Our story also has two 15th-century protagonists: Procopius (Prokop) Waldvogel of Prague and his business partner, a Jewish man named Davin (David) de Caderousse. The two met in Avignon in 1444 and tried to start an innovative business in order to promote the publication of a book printed in Hebrew. In the contract between them, which is preserved in the archive, there is mention of Hebrew and Latin letters, along with instruments and equipment for printing, a secrecy agreement and a patent registration. Their partnership disbanded and ended in a lawsuit, thanks to which there is written evidence of their existence.

In addition, Rosenfeld embarked on a worldwide quest to track down watermarks, which he calls the “fingerprints” of ancient manuscripts and printed texts.

“The manufacturers of paper embedded their symbol in the paper by means of watermarks,” he explains. For years, experts prepared catalogs of watermarks in which they classified them according to their years of production, which were determined based on a comprehensive archival study. “In that way, we reached a situation where, when a manuscript or a book was found without any dating but whose pages have watermarks, we can date them almost precisely,” Rosenfeld says.

Rosenfeld’s pages have a rare watermark: three hills inside two rings. Professionals who study watermarks date this image to the first half of the 15th century. In other words, the paper on which the pages were printed was created before Gutenberg was credited with being the inventor of the printing press. Scholars also believe that, at the time, paper was generally used up to about five years from its date of manufacture.

“We discovered, through manuscripts in libraries in Vienna, Palermo and Perpignan, and in the Ambrosian Library in Milan, that the watermark with the two rings is unique to the period between 1418 and 1439,” Rosenfeld says.

Drawing conclusions

Rosenfeld wasn’t satisfied with that, though. With the help of experts, he developed software that he describes as “a new system for examining Hebrew letters.” Thanks to this, he was doubly confident about his assertion regarding the dating and authenticity of the book.

Yudlov, who identified the potential discovery back in 2015, describes Rosenfeld’s research – conducted with Dr. Elyakim Kassel and others – as “a comprehensive and thorough study,” which “reinforces what I wrote in my 2015 article, regarding the assumption that apparently we have here an attempt at printing carried out by David de Caderousse.”

Yudlov says there is “interesting evidence from which we can definitely draw a conclusion.”

And what is that conclusion? Rosenfeld, of course, is convinced that these pages are the last remnants of the two partners’ work in 1444. If he is right, this Jewish prayer book will be the Western world’s first printed book (that we know of).

For now, the book is residing in the home safe of the American Jew who bought it. If the academic world ultimately confirms Rosenfeld’s conclusions, it will probably be worth millions of dollars. Its historical, public and national value, though, would be priceless. However, a major obstacle still awaits Rosenfeld: convincing the National Library of Israel.

“The opinion of the authorized professional bodies in the library at present is that there is no evidence that these pages are from a book printed in the 15th century. The authorized bodies in the library have never presented a different public opinion on the subject,” wrote National Library rector Shai NItzan recently, in response to a request from Rosenfeld.

“I’m not seeking honor or money; just the honor of the first book printed in the West,” Rosenfeld says. In spite of elicting some media response during various stages of his research, the academic world still refuses to get excited about his findings.

When asked why this is, Rosenfeld speaks of ego battles and internal politics. He claims that the expert scholars are incapable of admitting that a 70-year-old man who failed to complete his master’s degree in his youth, a mere “book dealer” – as some of them disdainfully refer to him – is responsible for a study that might have entitled him to a professorship.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO