Jewish Israelis are heading to Arabic class — and learning a bit more about Palestinians

‘I thought it was absurd that Jews don’t know Arabic and lots of people agreed with me,’ said Gilad Sevitt, who developed a popular online course to teach it

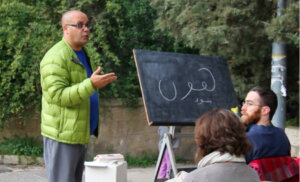

Palestinian and Jewish women learn each others’ native languages at Spoken Jerusalem-ese, a group that organizes conversation circles and field trips. Photo by Lior Urian

Israeli public schools require students to study Arabic, but the instruction is often either poor or doesn’t stick, and most Jews retain none or very little of it.

An increasing number, though, are committing to learning the language as adults, many of them reasoning that relations with their Arab neighbors, and the future of Israeli society, requires more Jews to understand the mother tongue of a fifth of its population.

To that end, Tal Rubenstein, 24, attends a Jerusalem conversation circle that regularly draws about 50 women, half Jews, half Palestinians, where they teach their native languages to each other. At one recent gathering, a Palestinian woman brought along her infant, who contentedly bounced from lap to lap.

“Like everyone else, I studied Arabic in school,” said Rubinstein, an elementary school teacher. “But I still couldn’t speak, or talk to my neighbor — or even make funny Arabic sounds to a baby,” she said.

Such conversation circles, and Arabic language schools, have proliferated in Israel in recent years.

The first-ever Festival of the Arabic Language and Culture attracted hundreds of Jewish Jerusalemites. For two days they could take a sample lesson from Arabic language teachers and browse book stalls selling everything in Arabic from textbooks to copies of “The Little Prince.”

It’s all part of a growing movement to correct what many Israeli Jews — sometimes for different reasons — describe as a problematic gap in their education. Dozens of initiatives to teach Arabic to Jews have sprung up, from private language schools to workplace classes to immersive courses in Israeli villages.

The trend is particularly noticeable in Jerusalem, where, according to linguist Anwar Ben Badis, one of Israel’s best known teachers of the language, there are at least 20 such initiatives, enrolling thousands of students.

Gilad Sevitt, 30, a Jerusalem Jew who founded an online Arabic learning forum in 2014 called Madrasa, or “school” in Arabic, now serves 110,000 students with free videos that allow them to learn the language at their own pace.

“I thought it was absurd that Jews don’t know Arabic and lots of people agreed with me,” he said. “Hebrew -speakers are the majority in this country, but we are certainly a minority in the region. It’s just logical that we learn to speak Arabic, too.”

‘The enemy’s language’

The first language of Israel’s Arab citizens is Arabic, but an overwhelming number — 92% — have some command of Hebrew.

“Arabs learn Hebrew for practical reasons, because, as a minority, they need to know the language of the majority in order to get along, but Jews do not ‘need’ to know Arabic,” said Ben Badis, who was born in an Arab village, and counts government officials, media personalities, and academics among his students.

In Jewish schools, the study of Arabic is compulsory in grades seven through 10. But according to a 2018 report by Sikkuy, an NGO that promotes equality between Israeli Jews and Arabs, there is little enforcement and the quality of instruction is deficient. Ten percent of Israeli Jews understand some Arabic and a scant 2.6% are able to read and understand Arabic-language media.

Those who learn Arabic in high school often do so in order to be accepted into elite intelligence units during compulsory military service after they graduate. In his 2014 book “The Creation of Israeli Arabic: Security and Politics in Arabic Studies in Israel,” Yonatan Mendel, a senior lecturer in the Department of Middle East Studies at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, writes that this militarized pedagogy alienates Jewish-Israeli students from Arabs rather than serving as a potential bridge between them.

“I’m trying to help free the Israeli student to stop thinking of Arabic as the enemy’s language and to start thinking of it as a way to connect with their fellow-citizens,” said Ben Badis.

Compounding the language gap is that most Israeli schools, if they do teach Arabic at all, teach classical Arabic, which has different grammatical rules and vocabularies than spoken Arabic. And Arabic differs from region to region. The new language initiatives all emphasize that they teach spoken Arabic in what’s known as the Palestinian urban dialect — that spoken in Jerusalem.

While the number of Jewish students interested in learning Arabic had been growing for at least a decade, the trend really took off, Ben Badis said, in 2018, after the Knesset passed the controversial Nation Law, which, among its other provisions, downgraded the status of Arabic from an official language of Israel to a language with a “special status.”

He sees the drive to learn Arabic as somewhat of a backlash.

“The Nation Law is an offense against the Arab citizens of Israel and their language,” Ben Badis said. ”There is a large population in Israel, and especially Jerusalem, who want to live together as equals and who know that studying a people’s language and culture is an important way to reach that goal.”

‘Something hopeful here’

Learning Arabic for many native Hebrew speakers is best done socially, with Palestinians who also want to brush up on their Hebrew.

At the Silo Cafe, a laid-back coffee shop in South Jerusalem, each week between 20 and 30 Jews and Palestinians meet for the “Language Coffee Shop.” Yonatan Lavi, a Jew from West Jerusalem, and Razan Hiyatt, a Palestinian from East Jerusalem, run the group, which is supported by the local community center.

The students also come from East and West Jerusalem, and they range in age from 20-somethings to retirees in their 70s. A core group comes every week, while others attend sporadically. Yonatan and Razan maintain a sign-up sheet to ensure that each week there are equal numbers of Palestinians and Jews.

After introductions — which the Palestinians must do in Hebrew and the Jews in Arabic — the leaders split the group up into Arab-Jewish pairs. For 25 minutes they speak to each other in Hebrew, and then switch to Arabic. Some speak fluently, others haltingly, the learning punctuated by frequent outbursts of laughter — linguistic stumbles, everyone in the room seems to understand, can often be funny.

Shahad Kiswame, a Hebrew University student wearing a hijab topped with a baseball cap, has teamed up with Tamar Alon, a retired teacher in her 60s who took up Arabic several years ago.

“Jerusalem is supposed to be a united city, but we can’t even speak each other’s language. How are we ever going to live in peace?” said Alon.

“It’s hard to listen to Palestinians talk about the occupation and inequality in Jerusalem, but still, there’s something hopeful here,” she added.

Spoken Jerusalem-ese — the all-women’s Jewish-Arab language group — capitalizes on what founder Lior Urian calls “the natural bond” between women. The single-gender nature of the gathering seems to make participants more comfortable, and allows them to speak more freely, she said.

Rubenstein, the teacher who wants to build on the little Arabic she learned as a teenager, is there. But so is Hodya Cohen, who wears a dress and head-covering in the style popularly known as “settler chic.”

The graphic design artist, 35, said she does indeed live in a settlement in the West Bank, and that she grew up going to a religious school in Jerusalem. Unlike Rubenstein, she said, because religious schools are exempt from teaching Arabic, she didn’t learn it even a little.

What motivates her now?

“Learning more about my neighbors and their language is crucial, because we are going to have to live together,” she said.

Urian, who is Jewish, said the group emphasizes language as culture.

She compares Arabs’ many blessings and greetings, and their often formal manners, to Israelis’ more abrupt and direct style, with its “informal chutzpah.”

“We don’t know their codes, we don’t know how to address a person in a respectful way, we don’t know how to interact,” she said. “It’s important that we learn, because we want to live together in this city.”

Today, Spoken Jerusalem-ese has more than 2,000 women, with 16 volunteers and two paid staff members. They meet in four Jerusalem locations and make field trips to different parts of the city. Urian said it surprised her to see that the Arab women were just as hesitant to visit West Jerusalem as Jewish women were to visit Palestinian neighborhoods.

“I know there is an occupation, but somehow I never think of Jews as threatening. Well, they do see us as threatening, and that is important to know,” she said.

Sevitt, who started the online community for Arabic learners, said that besides building bridges to Palestinians, there is another reason for Israeli Jews to learn Arabic.

It’s their own family’s language, too.

“Many of our parents and grandparents came from Arabic-speaking countries, and Arabic is their mother tongue. But the State of Israel denigrated Arabic to build up the Jewish nation,” he said.

“This distanced many of us from our own families. Learning spoken Arabic is a way to reconnect.”

The conflict enters the conversation

Some of the most serious Jewish students of Arabic end up in the classroom of Ben Badis, who teaches in two of Jerusalem’s most demanding programs — one at the Jerusalem Intercultural Center on Mount Zion and the other at the Museum of Islamic Art.

Both are heavily subsidized by the government and offer five levels of 32-week courses, for beginner to advanced speakers. Together the schools enroll about 8,000 students, each paying $600 for each level on average.

Ben Badis requires that his students speak Arabic, even as beginners. He aims to cultivate a respect for the language — but also more than that.

“I am teaching them to appreciate the language and the culture. I am teaching them about my own history, my grandparents, my family.”

And that is how the occupation and the Palestinian cause enter the conversation.

Ben Badis said he knows he’s not a political science professor, “but we cannot ignore what has happened here, what happened to my people in Israel’s War of Independence, which we call the Nakba,” he said, using the Arabic term for catastrophe.

“My grandmother grew up in what is now West Jerusalem. Her house is still standing, and Jewish people live there,” he said. “I use my language to communicate, but also as a resistance, to protect my identity.”

At the same time, he said, he tries to avoid overt political discussions, even if he knows that most of his students are sympathetic to his opinions. He also knows that not all are, and said that as a language teacher, he respects their right to hold views different from his own.

One student of his — a 36-year-old, strictly observant Jewish woman who works in public service, declined to give her name because, she said, her family does not know and would not approve of her studies — but freely acknowledged her right-wing politics. She studied in nationalistic schools, and was evacuated from a settlement during Israel’s disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

“I’m not here for the same reasons that most of the left-wing students come here,” she said. “I am not here to learn to communicate with Arabs. I am here to understand their language because I think it is important to understand the language of your enemy.”

Sharon Mizrahi, also a student in Anwar’s class, shakes her head at her classmate’s reasoning. “I’m here because I hate when we are defined as enemies of each other,” she said.

“The more the conflict becomes desperate or violent, the more I want to understand Arabic,” she said. ”For me, studying Arabic is a way to stay hopeful.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO