New book explores the insane career of Syrian Jewish hustler ‘Crazy Eddie’ Antar

Turns out he was a crook who fled to Israel and spent time in the same jail where Adolf Eichmann was executed

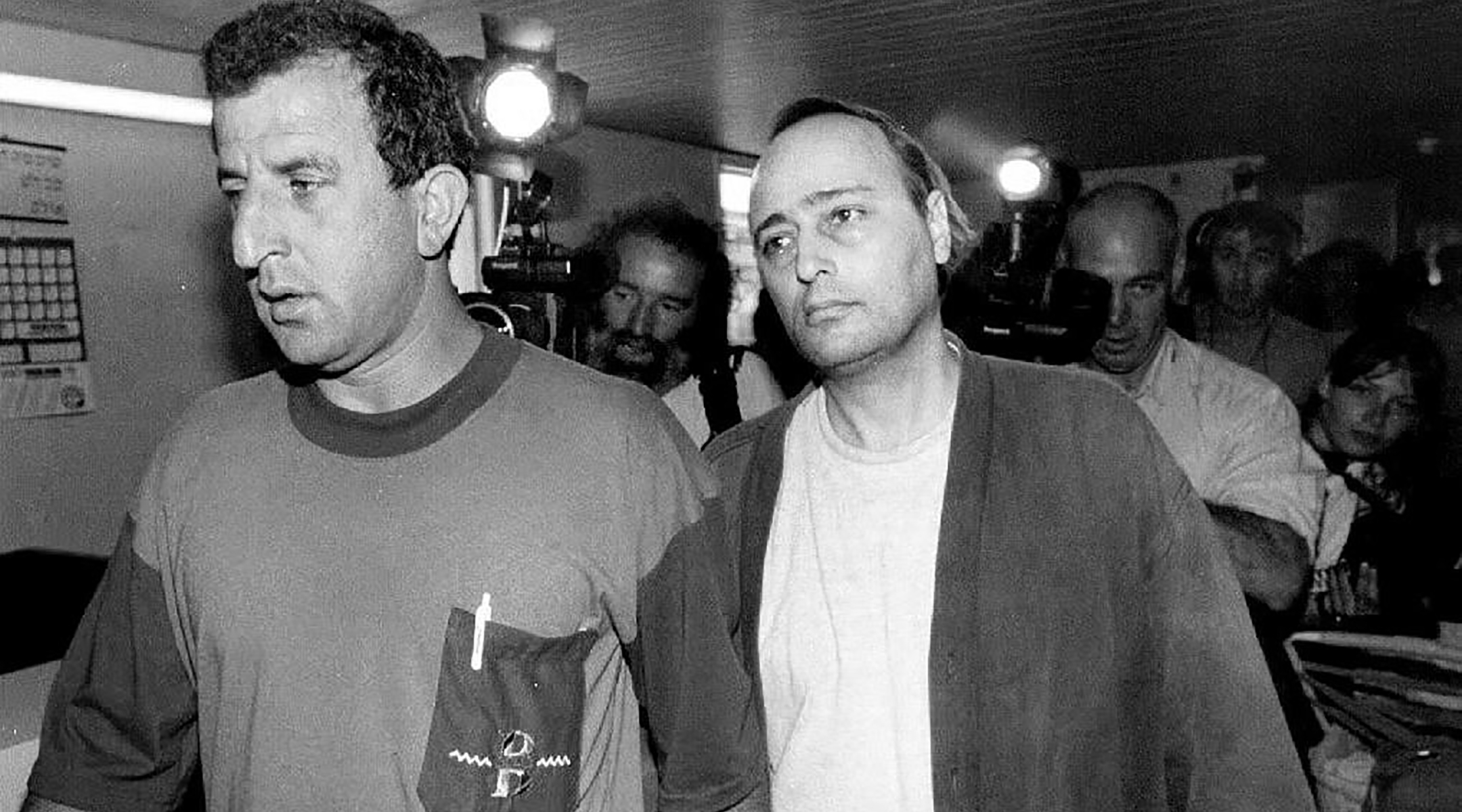

Eddie Antar, right, once known as “Crazy Eddie,” New York’s electronics king, is led by an Israeli police detective in Petah Tiqva, Israel, June 25, 1992. (Sven Nackstrand/AFP via Getty Images)

(JTA) — Crazy Eddie was a consumer electronics empire built on hype. Entrepreneur Eddie Antar grew his chain of discounts stores in the New York of the 1970s with unforgettably loud TV commercials, a reputation for low prices and a compelling story about an underdog family of Syrian Jews who had fled persecution and built a successful business.

It was also, alas, a business built on fraud.

The complete story of the rise and downfall of Eddie Antar and the Crazy Eddie chain is told in a new book called “Retail Gangster: The INSANE, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie,” written by veteran investigative journalist Gary Weiss.

The Crazy Eddie chain, which closed in 1989, didn’t just execute one big scam, it ran dozens of them at once. The company, for several years, pocketed sales taxes. There were multiple varieties of accounting fraud, warranty scams, used products sold as new and questionable reporting of financial results. All along, there was plentiful nehkdi — Syrian slang for cash-only transactions — by the people running the business.

It all ended with the chain dead and multiple executives behind bars.

Weiss has long specialized in stories of business malfeasance, and the Crazy Eddie story is one of the most colorful in recent history. He said he was first interested in the project when Sam E. Antar, Eddie’s cousin, colleague and ultimately a key witness against him, became a commenter on Weiss’ blog in the early 2000s. Weiss had been working on the book, off and on, since 2008.

“It’s such a huge story. I mean, it’s got so many tentacles,” Weiss told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “It’s a family story, it’s a business story, it’s a retailing story, it’s a fraud story. And it’s also a story of New York in the 1970s and ’80s…. It took awhile for me to sort of bring it all together in a coherent narrative.”

Weiss, who is Jewish and a New Yorker, said that he spoke to members of the Antar family and other sources, while also fishing through “voluminous” public records from various indictments, investigations, lawsuits and trials.

Not everyone involved in the story agreed to talk to Weiss, he said, and Eddie Antar died in 2016, before the author had a chance to try to interview him. But for many of the people involved, Weiss said, “I had something better than an interview: I had their sworn statements that were almost contemporaneous…. I basically had the story from their own lips, not too long after the events in question.”

While he mostly avoided the press and was rarely photographed, Eddie Antar left behind a story full of wild details, even beyond his many crimes. Both his first and second wives were named Debbie, referred to by those close to him as “Debbie I” and “Debbie II.” It was commercial pitchman Jerry Carroll, not Antar, who delivered the famous “His prices are insane” line on the television commercials, to the point where many New Yorkers thought Carroll was Crazy Eddie.

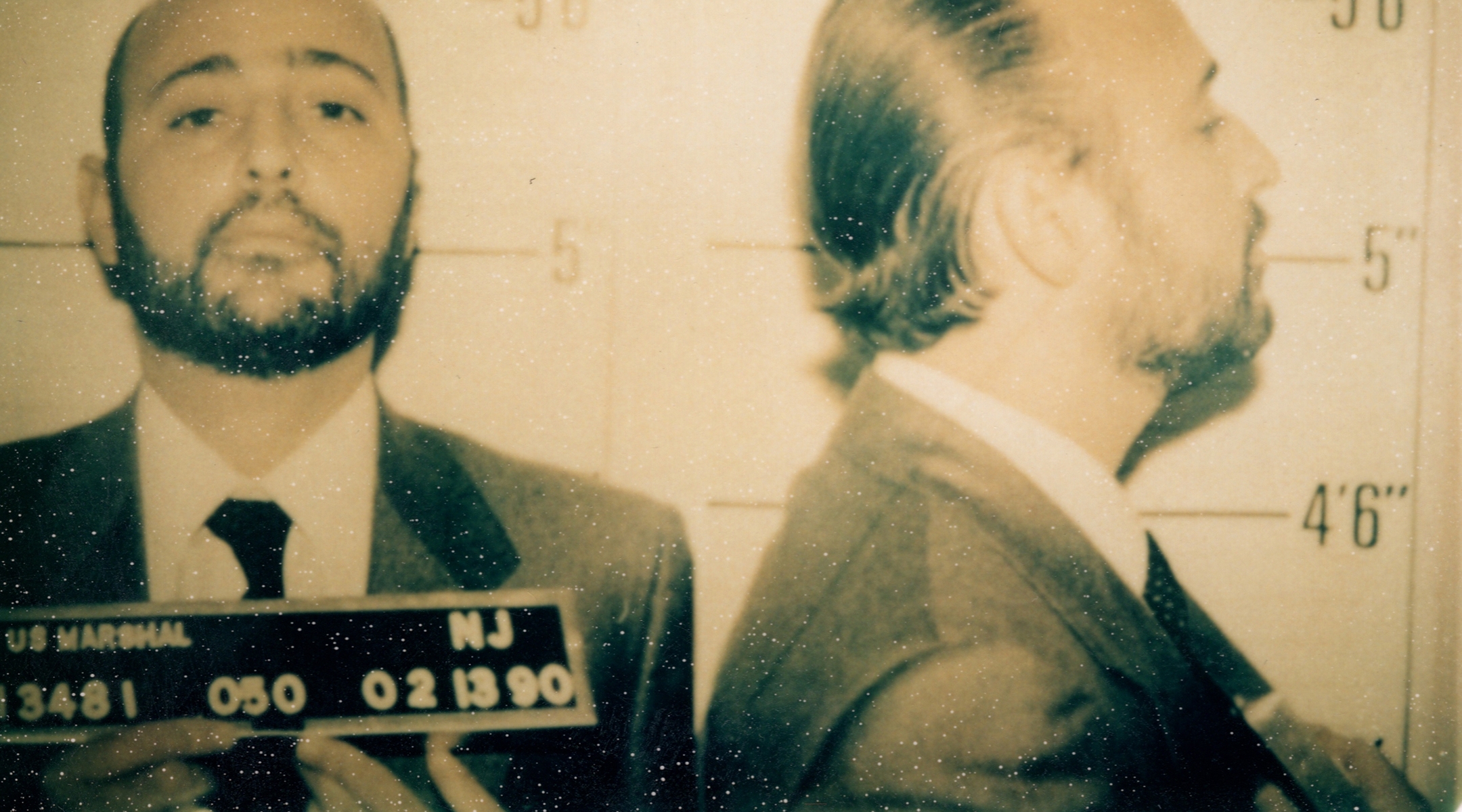

Antar stands for a mugshot after being arrested. (Courtesy of Paul Hayes)

Very important to the rise of Crazy Eddie was that the Antar family hailed from New York’s Syrian Jewish community, known as “SYs.” Eddie’s grandparents fled Aleppo, then part of the Ottoman Empire, in the early 20th century, landing in Brooklyn. It was a close-knit community, one that shunned intermarriage even with Ashkenazi Jews, and which used community and family ties to succeed in the clothing and electronics trades. Another defunct New York-based electronics store chain, The Wiz, was also founded by a Syrian Jewish family. (“Seinfeld” fans sometimes confuse the two chains, thanks to an episode in which Carroll’s antics as Crazy Eddie were combined with the real-life slogan “Nobody beats The Wiz.” Jerry Seinfeld’s real-life mother, in fact, came from the Syrian-Jewish community.)

Being from that community, Weiss said, “shaped [Eddie Antar] in the sense that he was the product of a very insular community, an immigrant community, that had been persecuted by the Ottomans, and by the Arabs, for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years. The history of persecution, as a result of which, [they] developed certain business habits involving cash, mistrust of the government.”

He added, however, that “it’s a mistake to view Eddie as a sort of Jewish character, or a Syrian Jewish character. He was a criminal.” Weiss said that Eddie Antar would, in some interviews later in his life, blame “the culture” for his fate.

“But the Syrian Jewish culture was not a culture of criminality. It was a culture that came out of persecution,” Weiss said. “Maybe you’re not so anxious to give money to the Sultan. Maybe you deal in cash a great deal. But the culture of the Syrian Jewish community… was one of survival in the face of a hostile government. I think people should be careful not to view Eddie as an epitome of the Syrian Jewish culture, he absolutely was not.”

While Eddie Antar identified strongly as Jewish, his level of religiosity was somewhat hard to pin down. He did, however, hide massive sums of money in Israel, and ahead of his indictment, he fled there in 1990. He continued to commit crimes and scams during his time in Israel, including using the bogus alias “David Jacob Levi Cohen.” Even the notorious gangster Meyer Lansky, Weiss notes in the book, was sure to abide by the law during his own short-lived exile in Israel in the 1970s.

Eddie’s sojourn to Israel lasted about two and a half years, when he was brought back to the U.S. for trial; he went on to accuse the judge in his trial of antisemitism.

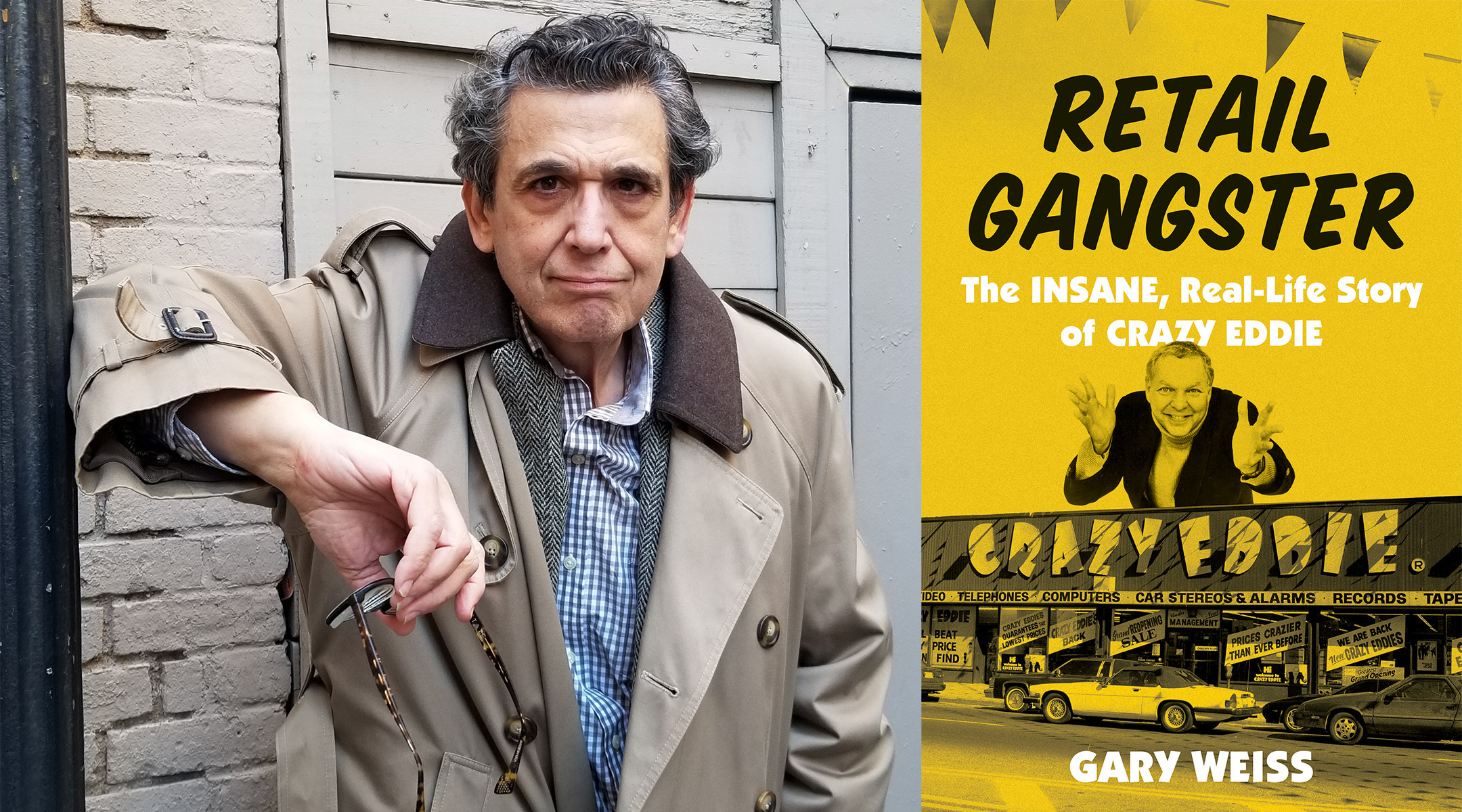

In his new book, Weiss describes the rise and downfall of Eddie Antar and the Crazy Eddie chain. (Hachette Book Group/Anjali Sharma)

“It’s hard to believe that a man who made a mockery of the Law of Return would be terribly religious,” Weiss said.

The Crazy Eddie chain grew at its height to more than 40 stores, and it also spawned many imitators, even one called “Meshuganah Ike.” But it was the company’s hubris, and its inability as a public company to keep booking fake profits forever, that ultimately brought Crazy Eddie down.

Antar served about six years in prison, and even six years after his death, victims are still trying to claw back some of the money that he was convicted of stealing.

Even with the benefit of computers, the Internet, digitized records and post-Enron accounting laws, Weiss believes that a scam like Eddie’s probably wouldn’t have been busted any faster if it happened today.

“I don’t think there would have been any difference,” Weiss said. “I don’t think analysts are any more skeptical than they were 30 years ago. I don’t think the public is any more skeptical. I don’t think regulators are any better, I don’t think the accounting firms are any better. I think the whole environment, the whole regulatory and commercial environment that Eddie was able to exploit, I don’t think that it’s even the slightest bit less hospitable to a scam artist like Eddie. The proof of that, I guess, would be [Bernie] Madoff… if you look at Madoff, Madoff was able to keep the scam going until the first decade of the 21st century.”

Many familiar Jewish names show up in the book. Stanley Chera, the real estate mogul and Friend of Trump who passed away early on in the COVID pandemic, was a relative of the Antars. Michael Chertoff, the rabbi’s son who served as Secretary of Homeland Security in the Bush administration, prosecuted Eddie Antar in his criminal trial. Raoul Felder, the prominent divorce lawyer and frequent New York media figure, represented the first Debbie when she divorced Eddie.

As for the Crazy Eddie legacy, there have been multiple unsuccessful attempts by Antar family members, most recently in 2009, to revive the Crazy Eddie brand in modern-day and presumably legitimate fashion. There’s also a Facebook group, with nearly 900 members, where former Crazy Eddie employees gather to share stories.

There have also been multiple efforts to make a movie about the saga. Danny DeVito announced plans in 2009 to produce and direct a Crazy Eddie movie, with the cooperation of the then-still-living Eddie Antar, although the effort was nixed the following year out of the concern that Crazy Eddie investors might take legal action against the filmmakers.

It was announced in 2019 that “National Treasure” director Jon Turteltaub would direct a Crazy Eddie movie of his own, called “Insane,” with Peter Steinfeld, also listed as the writer of the DeVito version, writing the script. However, there has been no word of casting or any other news about the project in the three years since.

Weiss’ book is dedicated to “the victims” of the scams. Who are those victims?

There was Eddie’s first wife Debbie who claimed that her husband hit her on one occasion, and also that he made numerous promises of a divorce settlement that never came to pass, until she ultimately won a hollow legal victory at a time when there was no money left to collect. But there were many more victims in a financial sense.

“The victims I guess would be the shareholders, the people who bought stock,” Weiss said. “Investors, customers, because customers were victimized by a myriad of schemes, ranging from bait-and-switch to being sold used goods as new. I’ve heard defenders of Crazy Eddie saying ‘oh, they got a great deal.’ They didn’t get a great deal. Crazy Eddie advertised an image of giving the cheapest prices, but they really did not.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO