At a polio vaccine clinic in Monsey, tensions between Orthodox and secular residents

The area, where an Orthodox Jewish man contracted the first U.S. case of polio in a decade, has long been a center of vaccine hesitancy

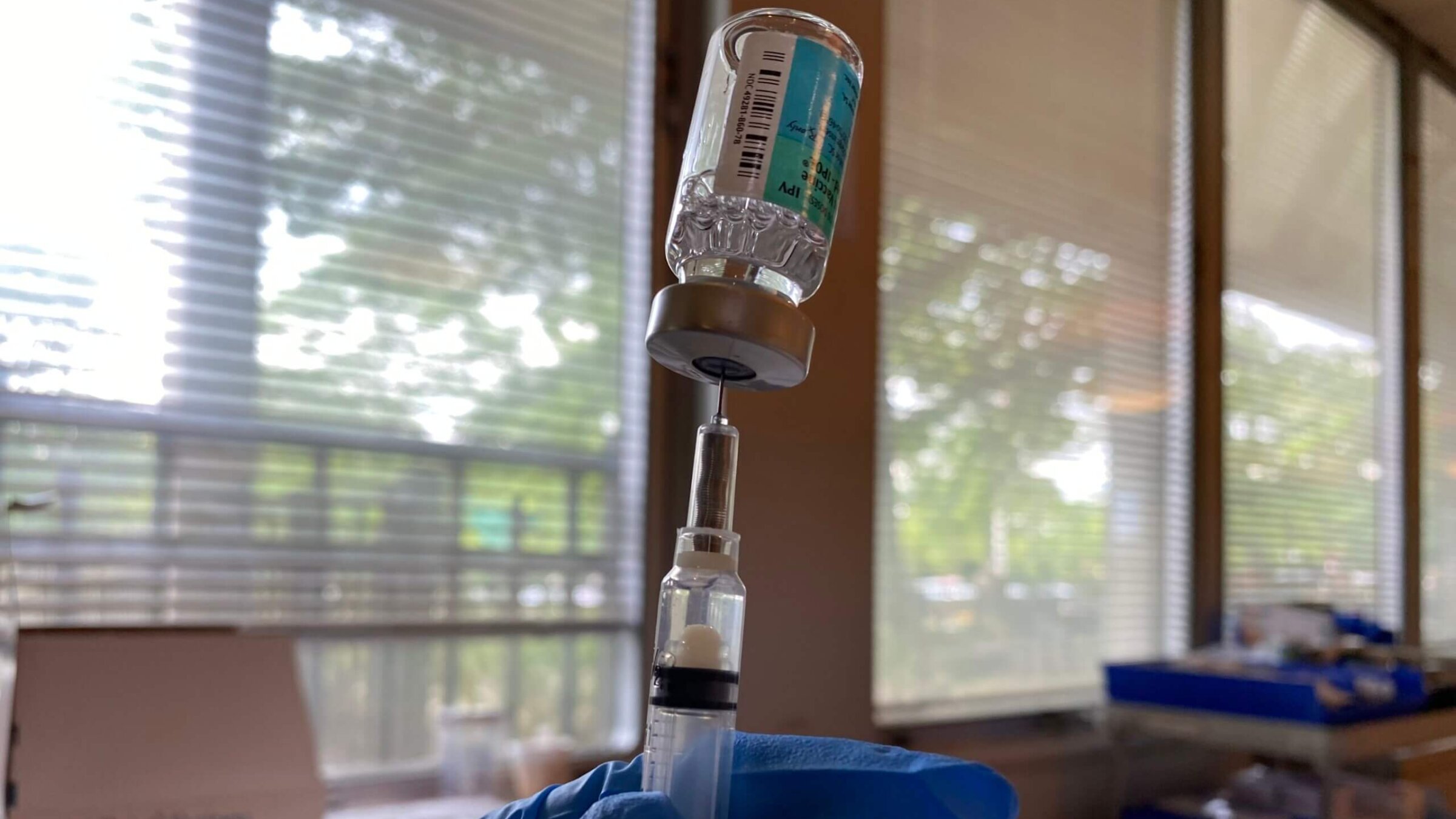

A nurse at a pop-up polio vaccine clinic in New York’s Rockland County measures out a dose of the vaccine. Photo by Rina Shamilov

MONSEY, N.Y. — When Barry Kupfer learned that the first U.S. polio case in a decade had emerged near his home in Monsey, New York, he knew immediately that he wanted to be vaccinated against the virus.

Kupfer, an Orthodox Jew in his 60s, could not remember whether he’d been vaccinated against polio as a child. He had a stem-cell transplant, so given the vulnerability of his immune system, he decided that even if he had, extra protection couldn’t hurt.

So on Monday afternoon, as a rainy morning gave way to sunny skies in Monsey, a heavily Orthodox town north of New York City in Rockland County, Kupfer was one of 53 people to get a shot at a pop-up clinic administering free vaccines.

Rockland County, which has the largest Jewish population per capita of any county in the U.S., has a childhood vaccination rate against polio of 42%, the lowest in New York State. It is also a place where tensions between the area’s ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, communities and their secular neighbors have long existed over public health as well as other issues.

There was a measles outbreak among the area’s Haredi population in 2019 and it was an early hot spot for COVID-19 as the pandemic began in 2020.

The Orthodox man who was confirmed last week to have contracted polio was not vaccinated against the virus, health officials said. He is said to be suffering from weakness and paralysis, but has not been publicly identified.

Monday’s was the second pop-up clinic since the case was announced publicly. County officials said they had so far administered vaccines to 379 people since the first case was confirmed.

While many in line seemed grateful to receive the potentially life-saving shot, the strain within the community was on clear display.

A young Hasidic man outside the clinic who declined to give his name said that he thought the reports of a new polio case “is a hoax” and dismissed warnings issued by local health officials.

“Polio is a joke,” he said. “No one had even had the virus in 50 years.” (In fact, there have been close to 200 confirmed cases worldwide since 1975.)

The man said that he had never been vaccinated and came to the clinic simply to “observe the scene.”

An Orthodox man in his 40s, who spoke on the condition he only be identified by his first name, Gabe, said he, too, was not vaccinated against polio as a child. As he waited to receive his shot, Gabe said he expects that Haredim will need to vaccinate their children before the start of the school year, even though most attend private yeshivas, because those schools nonetheless receive government-funded food and transportation services.

While in line, Gabe called a friend who works in local yeshivas. The friend, who declined to give his name, said many Orthodox Jews in the area were unaware of both the polio case and the pop-up clinic. He also downplayed the severity of polio, which can cause chronic health issues including paralysis and lead to death, by saying that “only a fraction of infected people experience symptoms.”

The New York State health department website estimates that 4% to 5% of people with polio have symptoms including fever, muscle weakness and vomiting, while 1% to 2% develop severe muscle pain and stiffness in the neck and back. Fewer than 1% of cases result in paralysis.

After hanging up the phone, Gabe bumped into his neighbor Janet, an older woman dressed in a bright blue blouse. Janet, who is not Jewish and also spoke on the condition she be identified only by first name, voiced her frustration over the vaccination hesitancy expressed by some of the Orthodox.

“How can people not vaccinate their kids?” she asked. “Why would anyone want their children to suffer? You can’t fix stupid.”

But most of the people at the clinic were calm and glad for the opportunity to protect themselves against yet another health threat after years of struggling to combat the coronavirus. Like Kupfer, the man with the stem-cell transplant, one elderly Hispanic woman said that she did not remember getting the vaccination as a child.

A white man in his 60s smiled and waved after receiving his vaccine. “Got it!” he said with a thumbs up.

“Wow,” another woman said to her companion as they exited the clinic. “That was really fast, efficient and lovely.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO