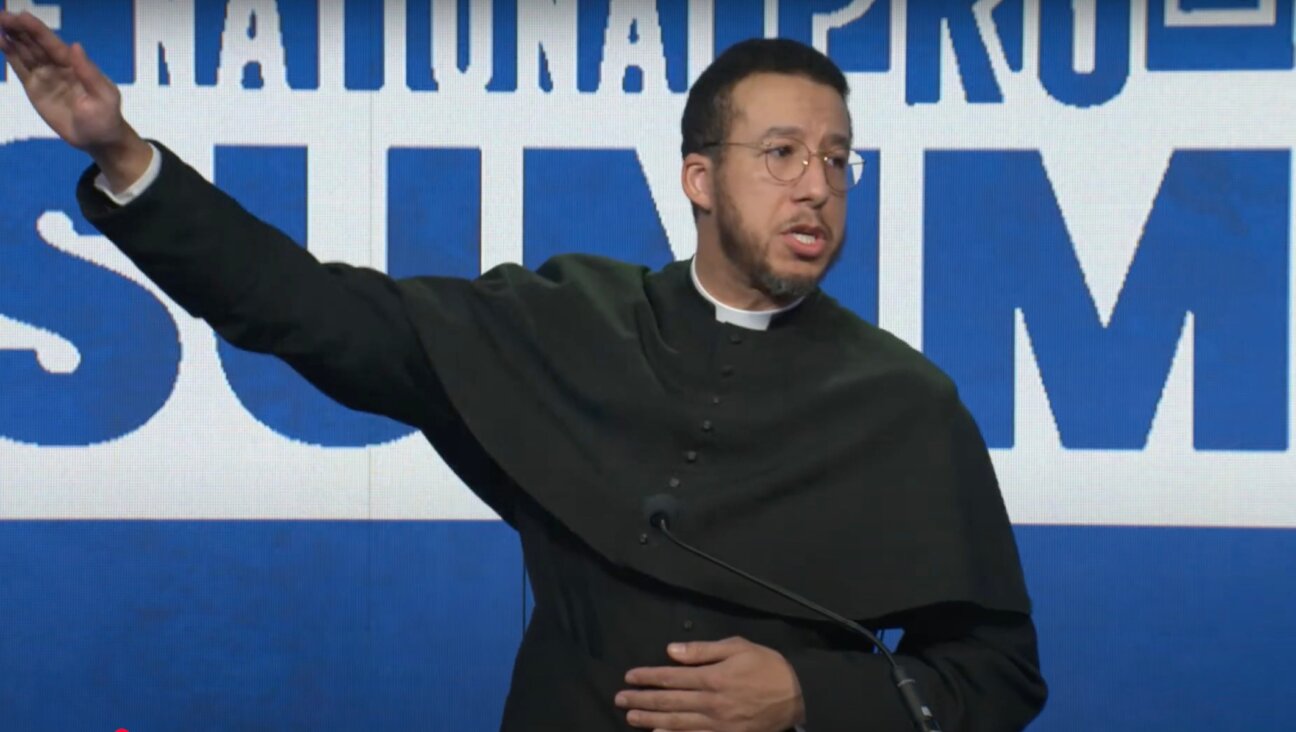

‘AIPAC lost its way’: Bill de Blasio says pro-Israel group has become too partisan

In exit interview, the former mayor and congressional candidate reflects on Israel, the Jewish vote and why he’s given up on electoral politics

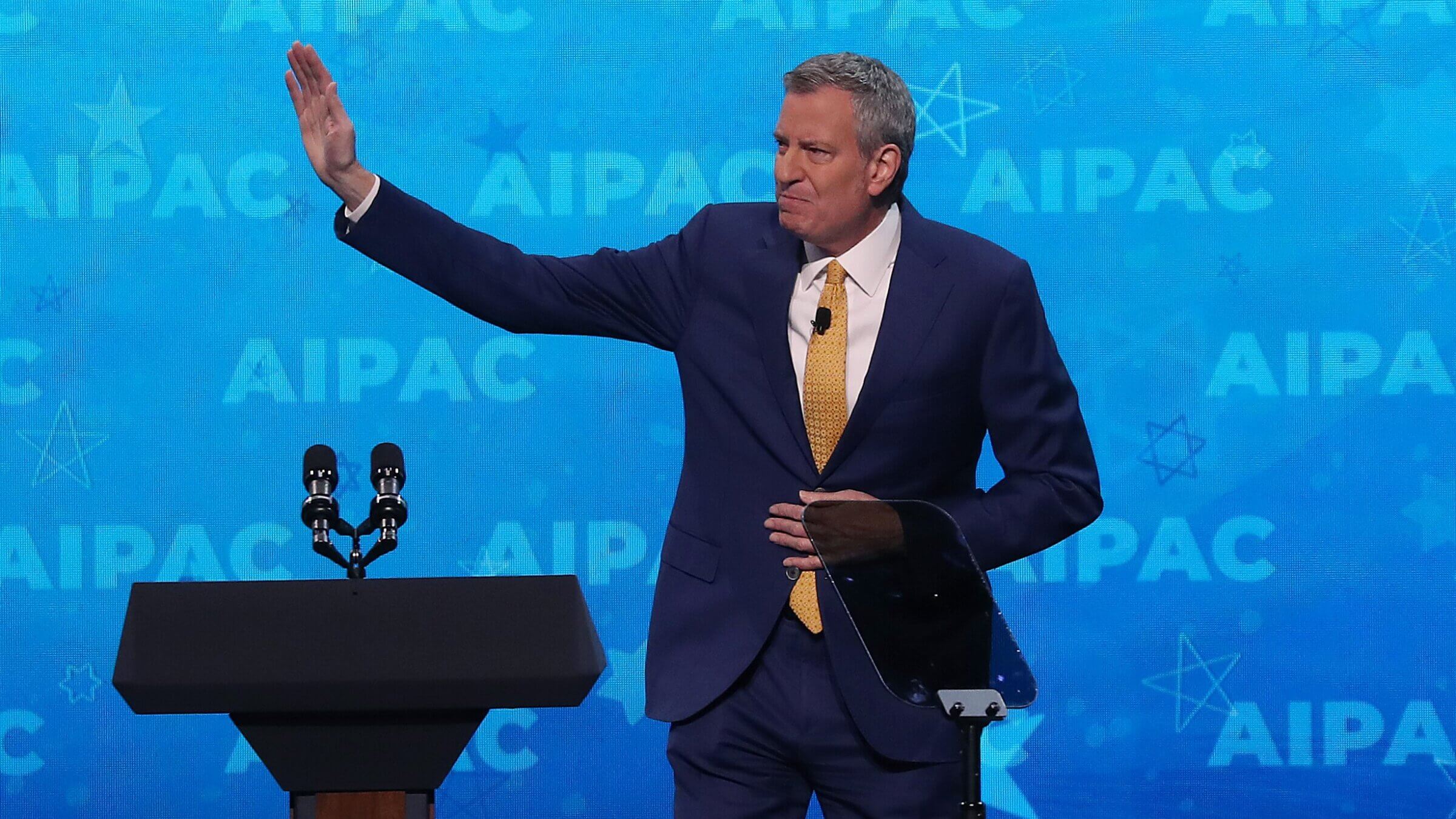

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio waves to the crowd after speaking at the annual American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) conference on March 25, 2019. Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Bill de Blasio, until recently a congressional candidate, surprised some allies last month when he came out forcefully against the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) over its spending against progressive candidates in Democratic primaries. “They have changed in a way that is unacceptable to me,” de Blasio said during a virtual candidate forum co-hosted by Our Revolution, a progressive political group supported by Sen. Bernie Sanders.

This was an about-face of his declaration at a closed AIPAC meeting in 2014, barely a month into his term as mayor of New York City, in which he told the crowd that “City Hall will always be open to AIPAC.” During his tenure, de Blasio was a frequent speaker at AIPAC local events and was a featured speaker on the main stage at their policy conference in 2019.

In an interview at a coffee shop in Park Slope last week, just days after he dropped out of a crowded primary for the newly redrawn and heavily Jewish 10th congressional district, de Blasio was unapologetic about his change of tone toward the pro-Israel lobbying group.

He said that AIPAC has slowly moved away from its big tent approach in recent years to a point where it has become closely aligned with Republicans and hostile to the progressive movement. But he didn’t pay much attention to that since he was busy leading the city’s response to the coronavirus pandemic.

“I was thinking old AIPAC,” de Blasio said. “And I awoke to find a different reality.”

The former mayor refused to say whether he initially sought AIPAC’s backing when he declared his congressional bid in late May, but he claimed that by the time he reached out to friends and donors about AIPAC, the group had already spent $11 million in some high-stakes primaries and endorsed Republicans who refused to certify the election of Joe Biden as president.

“I was literally shocked,” de Blasio said. “I’ve heard things I had not heard.” He also learned that AIPAC spent millions to defeat Nina Turner, a former national co-chair of the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign that he backed in 2020.

After reaching out to AIPAC and confirming what he described as “rumors,” de Blasio said he did his own research and came to a conclusion that he could not ask for, nor accept, an endorsement. “To me, AIPAC lost its way, lost track of its core mission, and unfortunately veered to one side, politically,” he said. “It is a horrible precedent and counterproductive.”

Without naming names, de Blasio said some of his donors and those active in the Jewish community have told him they also parted ways with the group. But he stopped short of endorsing Bernie Sanders’ declaration of war against AIPAC.

“I say this with hope and compassion, I wish they would come home,” de Blasio said of AIPAC. “I wish they would go back where they were. Because this model is not going to work. You can’t spend massive amounts of money to defeat progressives who have an organic constituency. And if they become a right-wing Republican organization, then they’ve just kissed goodbye to their entire concept.”

Marshall Wittmann, an AIPAC spokesperson, said in a statement, “We are proud of our involvement in a number of important races this cycle to help elect pro-Israel progressives to Congress. It is completely consistent with progressive values to support the one true democracy in the Middle East.”

Behind his announcement to quit politics

In the hour-long interview, wearing a button-down shirt with no tie and sipping on a bottle of iced tea, de Blasio seemed more at ease acknowledging his failings and discussing his strong relationships with Orthodox leaders during his mayoralty, sometimes at the cost of his relationship with liberal and secular Jews across the city.

Despite nearly universal name recognition, de Blasio’s ambition to advance his career was met with major roadblocks. After exiting City Hall on Dec. 31, he briefly flirted with a run for governor and then attempted to run in the initially redrawn 11th District, which included Staten Island and parts of his former council district in Brooklyn.

In May, after a judge released maps to replace gerrymandered ones that the state’s highest court voided as unconstitutional, de Blasio saw an opportunity. The 10th District, which now includes Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, was left vacant by veteran Democratic Rep. Jerry Nadler, who chose to run in the 12th district, where he faces longtime Rep. Carolyn Maloney, as well as two newcomers.

But a few weeks later, de Blasio found himself near the bottom of polls among the 15 Democratic candidates vying to represent the heavily Jewish district. First, a Data for Progress poll showed him in seventh place with 5%. Then a poll conducted by the Working Families Party found him with 3% support among registered voters.

De Blasio said his internal polling matched the same numbers. “There was way too much correlation,” he said.

Last Tuesday, after analyzing the polls, de Blasio released a video bluntly admitting the lack of enthusiasm for his campaign and announced he has given up on electoral politics.

Hours earlier, he spent two hours fielding questions from a dozen Orthodox voters about Israel, yeshiva education and his handling of the coronavirus pandemic in Hasidic neighborhoods. “I was almost experiencing cognitive dissonance,” he recalled of the late hours of Monday night when he was contemplating his next steps.

“But the fact is people were either tired of me or wanted a change so much that it didn’t even matter whether I might deliver more tangible change,” he said. “People are just not interested in what I have to offer at this point.”

While admitting he’s gotten the memo, de Blasio said he’s “sad” he was rejected by voters at a time he thought he had learned from his mistakes and figured out how to be a better communicator than in the past. But he said he’s “at peace” with the experience of 20 years in elected office.

Albeit late, de Blasio expressed remorse for the mistakes he’s made over the past eight years. “I became bitter at times. I became defensive. I became frustrated. I became kind of worn down by it all,” he said. “I now look back and think I could have attempted a very different relationship with the media.”

Support for Israel, from a progressive standpoint

On one issue, de Blasio said he feels he did the right thing, despite the backlash and negative media coverage: standing up in defense of Israel and voicing strong opposition to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against it.

“Defending Israel — from my point of view as a progressive — is a matter of being consistent with progressive values,” de Blasio said in remarks at the Hampton Synagogue in Westhampton Beach in the summer of 2016. In that speech, de Blasio challenged his progressive allies to oppose BDS.

He said in the interview that he came to a conclusion at the time that taking that position was the right thing to do because BDS denies the existence of the state of Israel as a homeland for the Jewish people.

“If you are on a campus today, and you love BDS, what would you have felt in 1948 when the Jewish people had just been through a Holocaust and were trying to have a state to be safe, would you be with them?” he asked rhetorically. “Probably a lot of these same people would have said, ‘Oh, look, they’re really the oppressed ones, I’m going to be with them.’”

“Well, they are not un-oppressed suddenly,” he continued. “The reality in the Middle East makes it complicated, and we just know enough about our history to know Israel was and is necessary, and antisemitism is profoundly alive. I don’t understand why people can’t see all that.”

But de Blasio cautioned against refusing dialogue with progressives who support BDS and oppose politicians who are critical of Israel “and thus create a bigger wedge.”

Instead, he suggested that Jewish and pro-Israel groups should engage with progressives leaders on common ground issues and reach out to younger Americans and understand that some supporters of the BDS movement are “attracted to it out of idealism, not out of hatred.”

De Blasio’s advice to the remaining candidates

A week before he quit the race, de Blasio condemned state representative Yuh-Line Niou, who said in an interview that she supports BDS, which aims to use economic pressure to force Israel to change its policies toward the Palestinians.

He advised the remaining candidates to do the same, or at the very least state their support for Israel and position against BDS. “Any candidate who can’t say that, in my view, should not be the congressman,” de Blasio said.

Being frank about his lack of popularity, de Blasio said he’s still undecided whether he will endorse a candidate in the race, but didn’t rule it out.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO