The creator of ‘Faces of Covid’ calls for a better monument to the dead than his own

At the 1 million COVID-death mark, Alex Goldstein continues to tweet out obits as he contemplates immeasurable loss

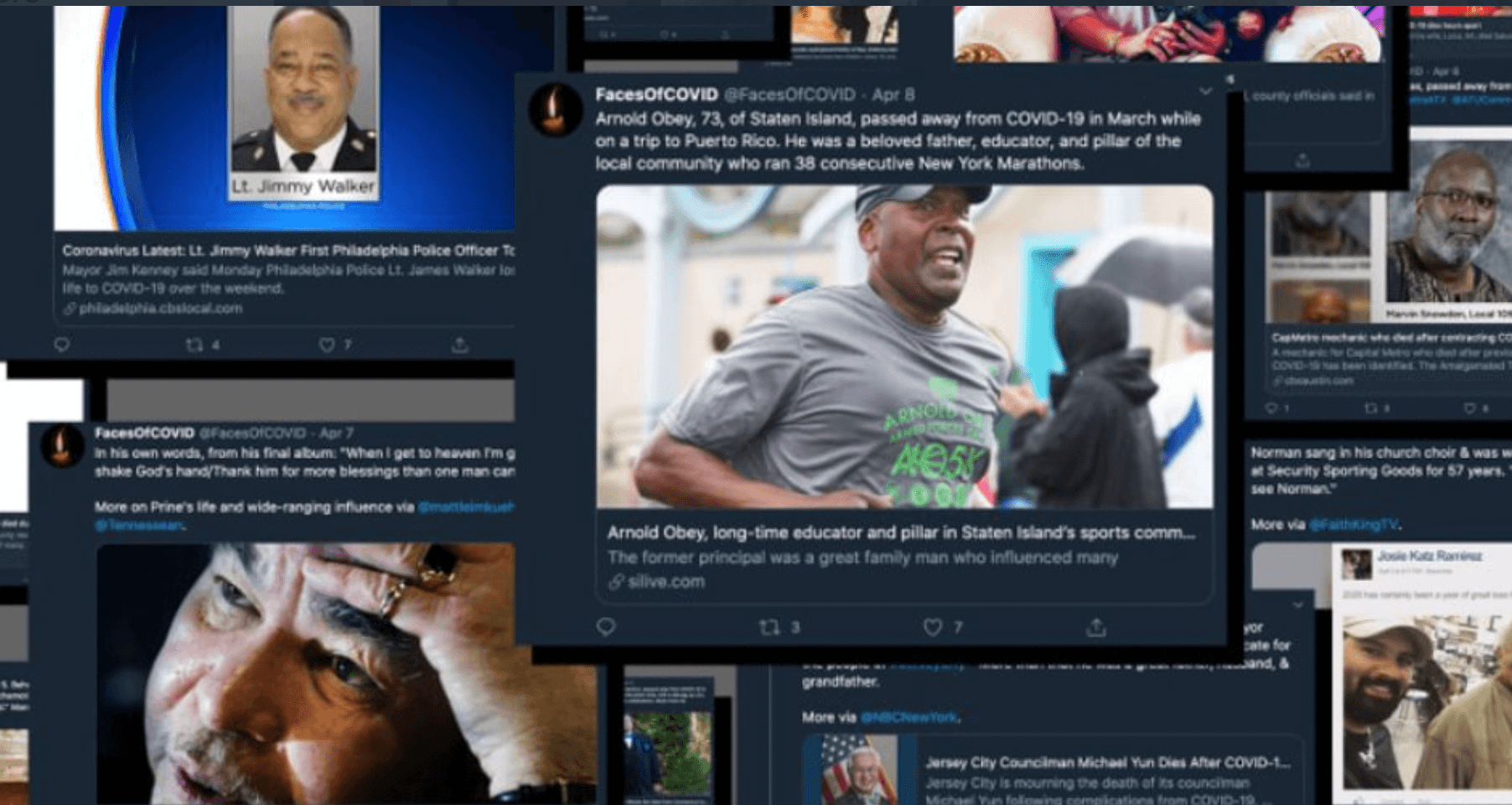

Alex Goldstein’s Faces of Covid account has tweeted more than 7,000 capsule-length obituaries since March 2020.

One million.

The U.S. is approaching or has already surpassed that number of COVID-19 deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, according to most calculations — a new order of magnitude of loss that is difficult to grasp. When the U.S. reached 100,000 COVID victims, The New York Times dedicated its entire front page to what it called “an incalculable loss.” What is 10 times incalculable, and how can people come to terms with the ever-expanding hole 1 million deaths has left in our social fabric?

There are few people more attuned to the scale of Americans’ pain in the past two years than Alex Goldstein.

Goldstein started publishing short obituaries of COVID-19 victims on Twitter in March 2020, pulling a few each day from news reports and reader submissions. Since then, the @FacesOfCOVID account has posted more than 7,000, each accompanied by a photo of the deceased. “A smile was on his face no matter what,” reads one, for a man from Florida named Donald Clayman. Another, submitted for an Alabama woman named Anne Gaillard, simply reads: “I miss her.”

Goldstein is Jewish, but the Faces of COVID are of many faiths, and no faith at all. Still, maintaining the account has felt like a Jewish ritual to Goldstein from the outset, reflecting the religious imperative to give dignity to the dead. He compared replying to or liking a Faces of COVID post to placing a rock on someone’s tombstone.

And though the project’s digital tombstones number in the thousands now, they account for less than one percent of the national sum. That’s one reason Goldstein, who founded a public relations firm and serves on the board of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Boston, believes there needs to be something more substantial than his Twitter page to memorialize the dead. Another reason is that he’s coping with his own experience of deferred grief: last April, his father died of cancer, and Goldstein was unable to hold the funeral he would have wanted due to a surge of COVID cases.

What remains is a lack of closure and a sense of isolation he believes is being shared by the masses.

“We are on the verge of a really catastrophic lack of processing,” Goldstein said in an interview. “And it’s hard not to look around and think that we have decided to forego what it really takes to process this amount of loss in the interest of moving expediently to whatever’s next, because it’s too painful.”

Goldstein started the account as a way to humanize the victims of a tragedy that was introduced to the American public through a series of numbers — case counts, incubation days, death rates — but which he became acquainted with through the howl of ambulance sirens outside his home in Waltham, Massachusetts, and a fire scanner app that told him they were for people with difficulty breathing.

At the time, he figured he would probably spend a couple months on the project before the pandemic subsided. Two years and two months later, the account has 150,000 followers, and writing the capsules is part of Goldstein’s morning routine, whether the disease claimed 5,077 people the day before — as it reportedly did on February 4, 2021 — or 50.

He has conflicted feelings about the success of his digital cemetery. He never intended for his project to become a clearinghouse for reporters looking for stories, or a lasting monument to the victims.

“The responsibility of carrying forward the memory of these folks and telling the full story of the extent of our losses from this pandemic — I wish it had been owned elsewhere,” Goldstein said. “I’m glad, I find it very powerful that people have found Faces of COVID to be something that they want to look at each day. But I don’t know that it was ever the right venue for it.”

Today, with widespread adoption of the vaccine and the prevalence of less lethal variants, the daily death toll is down as summer approaches. People want to turn the page, Goldstein says, especially if they have not been among the mourners. And because grief largely happens in private, even the mourners have little sense of how wide and deep the pain runs. But with 4 in 10 Americans knowing someone who died of COVID, grief is just under the surface everywhere you look.

He said he doesn’t have strong feelings about how space to mourn the victims should be created — it could be a physical site like a memorial, or a date marking the onset of the pandemic, or a more fully realized digital tribute. But without something to mark the loss, he worries the isolation Americans have felt growing over the past two years — and the political division it feeds — will become a permanent feature of our society, and that the lessons and the unity we could have taken from the pandemic will go to waste instead.

“The one thing that brings us all together is that when we lose somebody we love, it destroys us,” Goldstein said. “And the experience of mourning that together, regardless of who people are and where they came from, I think is actually the kind of empathetic way of engaging with each other that is part of the solution.”

If the challenges posed at the 1 million COVID deaths milestone recall the endeavor of memorializing 6 million Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust, Goldstein was reluctant to indulge too much in the comparison.

And he was not optimistic that passing 1 million deaths would be more impactful than passing 5,000 had been — or 500,000, for that matter.

But he offered one practical suggestion for overcoming the identifiable victim effect — the human insensitivity to large numbers.

“If you use the million confirmed deaths from COVID mark as an opportunity to tell one story of a person with a name and a face, and a story that was lost to this pandemic,” Goldstein said, “it will be a worthy reflection on one million.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO