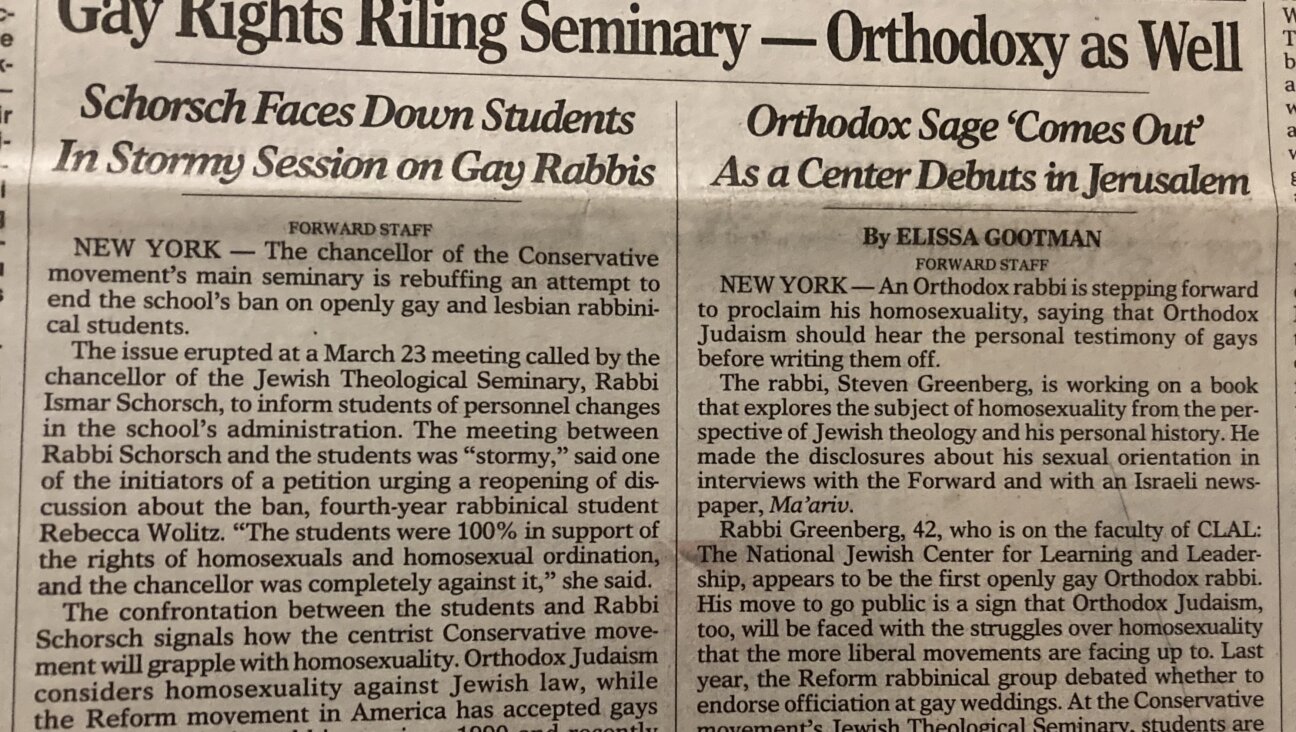

‘Cattle grazed among the bones of our sacred martyrs’: Covering Babyn Yar through the decades

In 1941, Soviet POWs bury victims of the massacre as Ukrainian women talk with a Nazi soldier. Courtesy of wikicommons media

It took two years for the Forward to first cover the 1941 massacre at Babyn Yar, a ravine in Ukraine, where the Nazis massacred more than 33,000 Jews over two days. The 1943 article came after the nearby city of Kyiv was liberated by the Red Army.

That feature piece by Avrom Leyb Hendin — who used the byline L. Hendin — cited the work of the two American correspondents permitted access to the killing fields. Those reporters, Maurice Hindus of the New York Herald Tribune and W.H. Lawrence of The New York Times, provided detailed accounts while Hendin, himself Ukrainian born, acted as the transmitter and commentator for readers of the then-Yiddish Forverts. Many of those readers had relatives murdered in the massacre, but only first learned of their fate through Hendin’s report.

“The Kyiv Jews had heard about the murderous Nazis and what had transpired in Poland and other occupied parts of Europe, but apparently didn’t imagine the Nazis would seek to murder Jews who were Soviet citizens,” he wrote.” The majority of the Jews, therefore, took along their meager remaining belongings to the gathering place they were ordered to. But when they gathered in the Lukyanivska area at the designated location near ‘Babyn Yar,’ a vast ravine in the region, Nazi soldiers shot them all.”

With a Russian missile having hit near the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial complex early in its current war with Ukraine, we took a look back to see how the Forward has covered the site through the decades. For most of this time, the site was referred to as Babi Yar, and Ukraine’s capital city as Kiev, using Russian transliterations, but we have updated our style to use the preferred Ukrainian spellings.

Years after Hendin’s initial report, our predecessors kept readers connected to Babyn Yar, with witness accounts at a Nazi war crimes trial, a detailed history of the event Kyiv Jews shared with a delegation of New York rabbis visiting in the 1950s, and dispatches from our Paris correspondent.

An aerial photograph of the Babyn Yar ravine taken by the German air force. Courtesy of USHMM/Wikicommons Media

In ensuing decades, we covered the Soviet government’s refusal to establish any memorial at Babyn Yar amid its oppression of Soviet Jews, and the regime’s disavowal of the massacre’s Jewish victims. In 1961, a young Soviet poet broke onto the Forverts front page with his groundbreaking Russian verse decrying official accounts of Babyn Yar, demanding his fellow citizens know the truth of the Jewish dead there.

With eyewitnesses to the atrocities largely gone, the Forverts back issues are an invaluable source bearing witness to what we cannot even imagine. This walk through the highlights of that coverage, its content and its tone, may offer today’s readers a deeper understanding of events unfolding there in our time.

A survivor’s testimony

In 1941, a huge fire burns on Kyiv’s main street due to Soviet time bombs exploding. Courtesy of Wikicommons Media/Bundesarchiv

In 1944, three years after the mass murder, the Forverts offered a special Shabbat report from the Kyiv trial of the lead Nazi perpetrator, identified here as Heinrich Markwart. The writer, Zalman Wendroff, was the rare Yiddish journalist whose beat included Jewish life in the furthest reaches of the Urals, a region lying between the Arctic Ocean and Kazakhstan; he had also covered both Russian revolutions (1905 and 1917).

Here, Wendroff gave Genia Einhorn, a Babyn Yar survivor, voice in the opening paragraph: “I’ve witnessed eyes gouged out and hacked off human hands” she recounted.

Einhorn, described as one of the few Jewish women survivors in Kyiv, testified against the Nazi leader of the 114th battalion of the German police whose long list of crimes were read at the trial and who was described there as an inventor of unimaginable tortures and a hangman on his days off. The judge said it was impossible to quantify the number of people Markwart had personally murdered. “Hitler knew who to send to Kyiv,” the judge said at one point, noting that the defendant had been recognized for his service by Heinrich Himmler.

On the witness stand, Wendroff reported, when Markwart was shown a photograph of a young woman and asked to identify her, he responded with clenched lips: “I killed her, I don’t recall why.” Markwart had received Gestapo Chief Heinrich Himmler’s recognition for his service.

‘Killed, doused with gasoline and burnt’

A Jewish gravestone from the Kyiv Jewish cemetery near Babyn Yar. By Adam Jones/Creative Commons

It was a small item, relegated to the fourth page on Aug. 10, 1956. “Russian Jews Beseech American Jews Not to Forget Them,” read the headline. Essentially a travel diary, it was written by Rabbi Israel Mowshowitz, who had recently returned from a visit to the Soviet Union with the New York Board of Rabbis.

“We traveled to Babyn Yar,” Rabbi Mowshowitz reported, “and on the way there we passed the old Jewish cemetery. There we met three Jewish elders we invited to join us.” They shared their stories of the massacre.

Mowshowitzs’ searing descriptions were among the first post-Holocaust ones we published.

“Babyn Yar is a ravine, three miles long, 30 feet deep,” he wrote. “There, Nazis shot 160,000 Kyiv Jews. They were killed, doused with gasoline and burnt, after which two inches of earth was shoveled over them. Jews returning to Kyiv after Nazi deportation found piles of corpses and human hair strewn across the entire pit. Cattle grazed among the bones of our sacred martyrs.”

Calling the Soviet Union to account

Discharged German bullet casings found near a mass execution site in Khvativ, Ukraine. Courtesy of Yahad-In-Unum/USHMM

By 1958, with the Cold War an accepted part of post-WWII reality and American Jews becoming rapidly upwardly mobile, the Forverts expressed frustration and rage at the Soviet Union’s refusal to memorialize Babyn Yar.

Calling it “one of World War II’s worst Nazi slaughters,” the paper aggregated news from London’s Jewish Observer: Moscow had overridden a decision of the Kyev City Council to commemorate its murdered townspeople. This report put the number of Jews killed at 100,000. “Ukrainians,” the article said, “participated along with the Nazis.”

Unironically, they concluded: “Moscow has other construction plans for that area.”

Bravery in verse

In 1961, the Forverts published the first full Yiddish version of Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s groundbreaking poem “Babi Yar,” translated by a Yiddish poet whose pseudonym was N.Y. Shortly thereafter, acclaimed Yiddish poet Yoysef Rubinstein had his translation published in our pages. Courtesy of Forward Archives

It took a poet and the youth culture of the 1960s to bring Babyn Yar to the front of public consciousness.

The Forverts initially described Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s public reading of the poem in Moscow as having been “very well received.” They translated it into Yiddish, excerpted critical lines and premiered it on September’s front page in 1961, explaining to readers the poet’s heroic act was his having dared to express that communism would only triumph “when the last antisemite on earth is buried.” In Yiddish, the line from the poem is: “Ven s’vet af eybik shoyn bagrobn veren der letster af der erd antisemit.”

Later Forverts headlines told of Moscow’s denunciation of Yevtushenko, who had written of the antisemitism of both the attack and its erasure. And the articles made clear the distance many readers felt from the Holocaust.

“‘Babyn Yar’ is the name of a Kyiv neighborhood where one finds the mass grave of many thousands of Jews murdered there under the Nazi occupation,” the Forverts said.

The “Collected Poems and Articles” of Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Courtesy of Jewish Culture Association

As much of America was consumed with Woodstock, Black Power, feminism and LGBTQ activism, Yevtushenko and the plight of Soviet Jews continued to be regularly featured in the Forward. His work was highlighted in a 1961 report on antisemitism and its resulting decline in the number of Jewish students in Soviet universities.

“Jew hatred is expressed in diverse ways here,” one article said. “Politically and culturally, antisemitism has increased in the USSR, while the government steps aside and does nothing against this evil — and might even be subtly encouraging it. And that is what Yevtushenko movingly spoke about in his poem.”

The paper followed that up with a cultural item from Israel’s daily Ma’ariv, which today reads like a cold harbinger of current Russian fake news: “Soviet poet publishes antisemitic ‘response poem.’”

Here Forverts readers learned of the dangerous lampooning of both Yevtushenko and Babyn Yar: “Alexei Markov’s anti-Jewish poem makes fun of Yevtushenko, calling him a traitor to his own people, for having called out Soviet antisemitism and Babyn Yar. What kind of Russian are you if you’ve forgotten your own people?”

And there was this Markov insult of Yevtushenko, which clunks a bit in translation: “You’re like a freshly pressed pair of pants with no one in them.”

A couple of days later, the Forverts reported that “thousands came out on Moscow’s streets” to greet Yevtushenko. On our old radio station, WEVD, the Congress for Yiddish Culture led an on-air symposium about the poem featuring Yiddish poet and literary critic Yankev Glatshteyn.

The editor of the Forward, Moyshe Morris Crystal, penned an editorial that same day decrying Russia’s dishonest attitude toward equal rights for its own minorities and its Jewish population specifically. “It’s remarkable how difficult it is to chase down a lie,” he wrote about Russia aggressive nationalism and denial of its official antisemitism.

The Forward’s Paris correspondent Leon Leneman’s piece, ‘Details About the Slaughter in Babyn Yar,’ was advertised as offering the history behind Yevtushenko’s poem – including “descriptions the Soviet government wants to suppress.” Courtesy of Forward Archive

Leon Leneman, the Forward’s Paris correspondent, was tasked with offering the “Entire History of the Babi Yar Massacre.” He told readers that “Khrushchev promised to erect a monument and promptly ‘forgot.’” Here’s Leneman’s description of Khrushchev’s official visit to the site after its liberation.

“While Khrushchev was at the death-pit of Babyn Yar, one could still recognize traces of the cruel, bestial slaughter,” he wrote. “Beneath fresh hastily scattered loose earth even now, one could see victims’ limbs protruding.” According to Lenemen, Khrushchev was saddened by the site, and committed that the Soviet regime would ensure a monument to the memory of the slaughter. But that did not happen. The official Soviet party line never referenced Jewish victims.

Lieutenant General Nikita Khrushchev during World War II. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Khrushchev anecdote was also in a 1961 article citing our Israel correspondent, Sholem Rosenfeld, who described a 1943 visit Krushchev made to the site when he was Ukraine’s Communist Party Secretary and a Soviet Lieutenant General in the newly liberated Kyiv. Rosenfeld, like Leneman before him, reported that Khrushchev had then given a stormy speech acknowledging the Jewish victims and swearing a monument would be erected in their memory.

Leneman, who in the early days of fascism had reported from Warsaw in intimate detail about Jewish refugee families and children deported back there from Germany, now reminded readers that official plans for Babyn Yar had included making it a garbage dump. He wrote about prayers in Kyiv churches asking forgiveness from the murdered Jews. And he mentioned an anonymous letter that Israel’s Davaar newspaper had received describing Kyiv Jews making annual Yom Kippur visits to the site, to memorialize their martyrs without detection by Soviet police.

Meanwhile, in 1961, construction to fill the site began as part of an expansion of the town center. Leneman reported on the catastrophes that befell the engineers as they struck ground. “A large plot of earth collapsed, tearing up entire streets and over 100 Ukrainian lives were lost,” he wrote. “The population, according to Moscow, began to panic, thinking the souls at Babyn Yar were taking revenge for Ukrainian collaboration and for bringing cattle to graze at the site of the mass graves.”

Days later, the Forward published another Yiddish translation of Yevtushenko’s poem, with an asterisk by the translator’s name: “Last Friday we published a translation by poet N.Y., and poet Yoysef Rubinshteyn did another version that we’re publishing here now.”

In 1966, on the 25th anniversary of the massacre, the Forward again highlighted Yevtushenko’s poem in an editorial condemning antisemitism “Recently, an American journalist has visited and described how masses of tourists visit Babi Yar,” it said, “and yet no historical signage exists to signify what occurred there 25 years ago.”

Fighting the official narrative

“Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel,” by Anatoly Kuznetsov, was published using the pseudonym A. Anatoli. Courtesy of farrar straus and giroux

Another young, heroic Soviet writer and Babyn Yar authority, Anatoly Kuznetzov, wrote a 1970 editorial devoted to “the defamation of Babi Yar’s victims.”

Kutznetzov’s groundbreaking documentary novel entitled “Babi Yar” had forced his defection from the Soviet Union. At 14, he had witnessed the mass murders, and he spent years researching and writing up the details. Now he was calling out the Soviet fake news organ Pravda, which had claimed Ukrainian Jewish leadership’s collusion in the murder of Kyiv’s Jews at Babyn Yar. Seemed at the time, that was one way to get Moscow to admit Jewish victims of the mass murder.

And in 1973, the Forward’s news editor, Borekh Fenster, reported on New York efforts to memorialize Babyn Yar.

The city had proclaimed “10 commemorative days,” his headline shouted. City Hall Park was renamed “Babi Yar Park.” The opening ceremony, organized by the Greater New York Conference for Soviet Jews, found Deputy Mayor Edward Morrison reading a proclamation on behalf of his boss.

In part, the official declaration promised that, 32 years on after the mass murder, humanity would forever remember the event. Additionally, it stated that Jews continued to suffer in the Soviet Union, as Mayor John Lindsay himself said he had witnessed during a recent visit.

Sculptor Cindy Jackson’s traveling Babyn Yar memorial project, entitled “Requiem.” By Cindy Jackson/US-Ukraine Foundation

Finally, on the 35th anniversary of the massacre, in 1976, a Forward editorial spoke again of Soviet defilement of the site.

“At each memorial date,” the editors pointed out, “Jews gather there to honor the sacred memory of their parents, siblings and friends.” They described these pilgrimages as “ a significant protest against Hitler’s fascist murders,” and a reminder “for the Jewish people as well as all humanity to ‘never forgive and never forget.’”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO