Nazi collaborator monuments in Romania

Octavian Goga is honored throughout Romania for his poetry. But as prime minister, he stripped a third of Romanian Jews of their citizenship

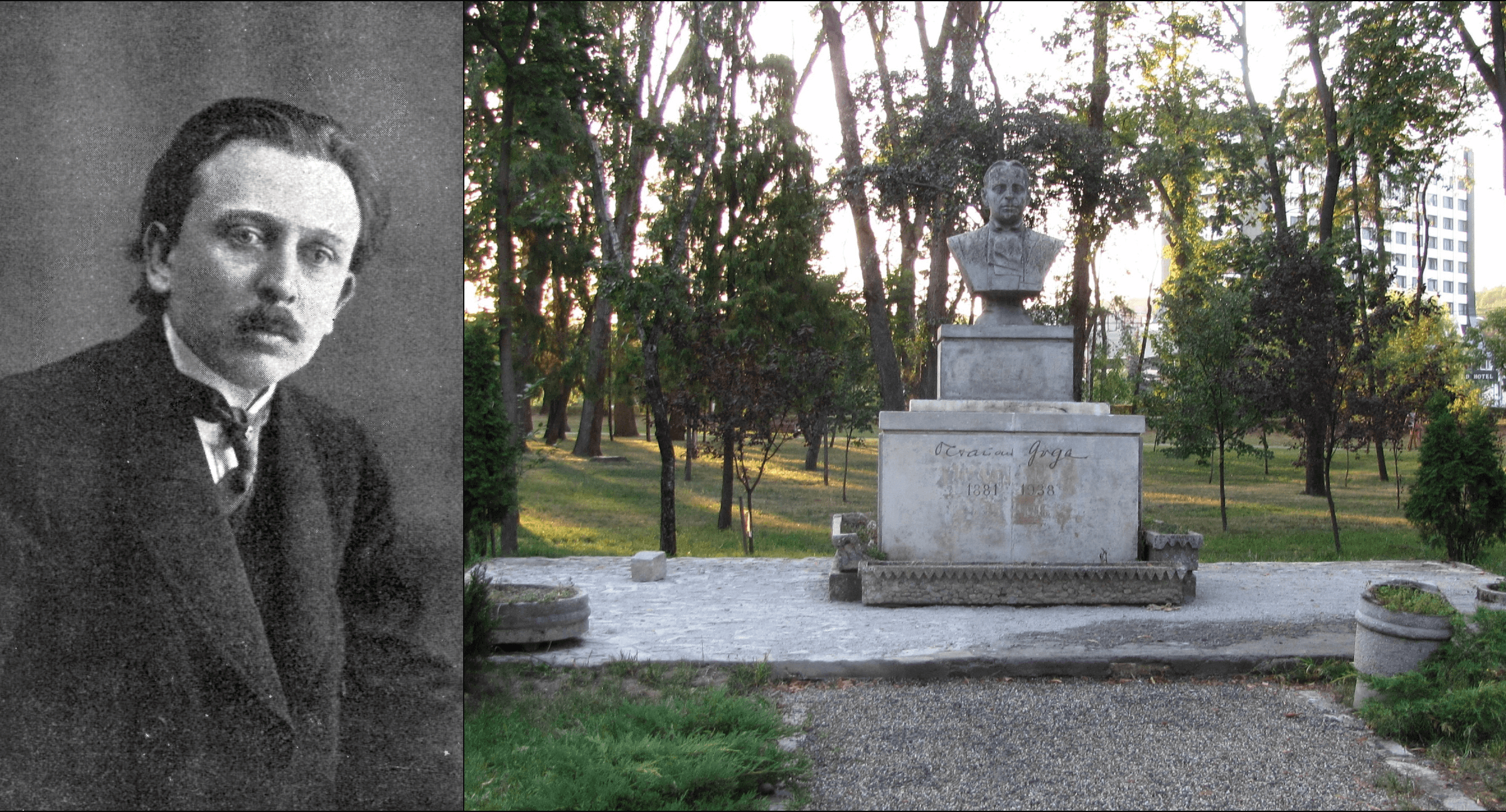

Left: Octavian Goga (Wikimedia Commons). Right: Goga bust at Central Park Simion Bărnuțiu, Cluj-Napoca (Wikimedia Commons). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Beiuș and eight other towns — For most of WWII, Romania was ruled by the dictator Ion Antonescu (1882–1946), a Nazi ally seen with Hitler in the photo below, June 1941.

During this time, Romania ran with the blood of over 400,000 Jews and Roma, who were butchered in pogroms, gunned down in ravines, imprisoned in unspeakable conditions, and deported to concentration camps for elimination. In 2004, a commission of international Holocaust experts concluded that “Romania bears responsibility for the deaths of more Jews than any country other than Germany itself.”

Marshal Ion Antonescu Street, Beiuș (Google maps). Image by Forward collage

Antonescu has other streets in 1 Decembrie, Bechet, Constanța, Mărășești, Predeal, Râmnicu Sărat and Turnu Măgurele, and a bust displayed in Sărmașu. However, in 2021 1 Decembrie and Constanța both voted to rename their Antonescu streets, although whether the changes have actually taken place is unclear. See coverage in G4 Romania (Google translation here) and Info Sud-Est (Google translation here ).

Many thanks to Emanuel Plopeanu for his detailed guidance on Antonescu and Alexianu rehabilitation. See his commentary on the Antonescu street in Constanța here, in Romanian (Google translation here). Thank you also to Marius Cazan and Maximillian Marco Katz for sharing their deep knowledge of Holocaust whitewashing in Romania.

Bucharest and two other locales — Romania’s capital hosts a bust, street, school and commemorative plaque honoring Mircea Vulcănescu (1904–1952). Economist, philosopher, ethics professor and convicted war criminal, Vulcănescu was undersecretary at the ministry of finance in Antonescu’s regime. Attempts to get Bucharest to remove the bust and rename the street have been unsuccessful. Vulcănescu also has a school in Bârsana and a street in Aiud.

Vulcănescu’s rehabilitation capitalizes on his status as an intellectual — he’s depicted as a mere “economist” or “philosopher,” which is how he’s described on his commemorative plaque. That’s a common tactic used by those who whitewash collaborators. See Vice Romania article on the scandal over Vulcănescu’s legacy (Google translation here).

Update (January 2023): this month, the city council voted against removing Vulcănescu’s bust in Bucharest. See coverage in the Jerusalem Post.

Costinești — A street named after Gheorghe Alexianu (1897–1946). As governor of Transnistria, Alexianu turned the region into a vast killing field for Jews and Roma. He arranged concentration camps to imprison Jews and Roma who had been deported to Transnistria from other regions in Romania and Ukraine. In 1942, Alexianu ordered the deportation of Jews from Odessa, a city where Jewish culture thrived; Odessa’s Jews were massacred afterward. Overall, at least 12,000 Roma and 280,000–380,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews were murdered under Romanian rule.

Below, German and Romanian soldiers deport Bessarabian Jews to concentration camps.

***

Alba Iulia and fifteen other towns — The majestic Alba Carolina Citadel has a bust of Miron Cristea (1868–1939), the cleric who became Romania’s prime minister in 1938. In the lead-up to the Holocaust, Cristea blamed Jews for Romania’s problems with statements like “One has to be sorry for the Romanian people, whose very marrow is sucked out by the Jews.” Such antisemitism is nearly identical to Goebbels’ depictions of Jews as insects. In 2010, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum vociferously objected to Romania honoring Cristea with a commemorative coin; the coin was minted regardless.

Cristea also has busts in Bucov and Râciu; a bust and a street in Năsăud; two busts, a school and a street in Toplița; a statue and a street in Caransebeș; a park (with a bust) in Amați; a school in Subcetate; and streets in Bistrița, Bucharest, Ciorogârla, Copăceni (Ilfov County), Gheorgheni, Lazu, Miercurea Ciuc, and Timișoara. See the Serbia section for a Cristea bust.

Cluj-Napoca and 89 other towns — A monument to Octavian Goga (1881–1938), poet and rabid antisemite who served as Romania’s prime minister before Miron Cristea (see above). Goga, who cofounded the antisemitic National Christian Party which featured a swastika in its logo and regularly engaged in anti-Jewish violence, used his time as prime minister to enact anti-Jewish legislation.

“The Jewish problem is an old one here, and it is a Rumanian tragedy. Briefly, we have far too many Jews,” Goga told the New York Times two days before enacting a law that stripped a third of his country’s Jews of their citizenship, a crucial step on the road to genocide.

This man is honored throughout Romania, ostensibly for his poetry; a very partial list includes a second bust, a street, a school, a plaque on the Faculty of Letters building of Babeș-Bolyai University and a library in Cluj-Napoca; a bust, street and school in Sibiu; busts and streets in Alba Iulia, Bucov, Sighetu Marmației and Târnăveni; monuments in Macea and Zalău; schools in Baia Mare, Huedin (with bust), Jjibou, Marghita, Oradea; a street and school in Miercurea Ciuc, Satu Mare and Sighișoara; a school and museum in Ciucea; a museum (with plaque), school, street and bust in Rășinari; and streets in Abrud, Agigea, Aiud, Arad, Bârca (Dolj County), Bârlad, Beclean, Berceni (Ilfov country), Bistrița, Blejoi, Brașov, Brebu Mânăstirei, Bucharest, Câmpia Turzii, Carei, Cerna, Cernavodă, Codlea, Cojocna, Constanța, Dej, Deva, Dumbrăveni (Sibiu Country), Dumbrăvița, Feldioara, Fetești-Gară, Focșănei, Hălchiu, Hărman, Iernut, Independența (Galați County), Ineu, Izvin, Lipănești, Mangalia, Mediaș, Moara Vlăsiei, Nojorid, Ocna Mureș, Oradea, Orăștie, Periș, Petrești, Petrila, Pitești, Postăvari, Râmnicu Vâlcea, Reșița, Săcueni, Sadu, Săliște, Salonta, Sânpetru, Sebeș, Șelimbăr, Sinaia, Smulți, Studina, Suceava, Tălmaciu, Târgu Jiu, Teiuș, Timișoara, Turda, Valea Călugărească, Valea lui Mihai, Valea Lupului, Valea Stânii (Călărași County), Vladimirescu, Vulpășeni and Zalău.

On April 1, 2021, the city of Iași unveiled a bust as well as a separate plaque honoring Goga. The choice of location is particularly reprehensible considering that in 1941, Iași was the site of horrific pogroms which massacred over 13,000 Jews. Goga’s fanning of anti-Jewish hatred helped lay the groundwork for this slaughter (see Iași pogrom survivor testimony, Yad Vashem).

After an outcry which included the Elie Wiesel Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania and antisemitism watchdog MCA Romania, the city added a plaque to the side of Goga’s bust. It states that “Unfortunately, his political activity is regrettable for the history of Romania because he was a fascist militant and antisemite.” This is an example of contextualization – the notion that instead of removal, monuments to despicable figures should be dealt with via plaques with disclaimers. Unfortunately, it achieves the opposite effect: the plaque makes it clear Iași is fully aware Goga was a fascist and antisemite, but is fine with glorifying him anyway. Shortly after being erected, the contextualization plaque was vandalized.

See coverage by G4 Romania (Google translation here and here) and Ziarul de Iași (Google translation here); NBC on the Iași pogroms; and the Moldova section for more Goga honors.

Cluj-Napoca and two other locales — Radu Gyr (1905–1975) was a Romanian poet, playwright and journalist. He was also a commander in the fascist Iron Guard, which carried out numerous pogroms. Today, Gyr is honored with a street in Cluj-Napoca, despite attempts by Romania’s main Holocaust research center to have it renamed. He also has a plaque in Bucharest and a street in Păun (Iaşi County).

Note: the Bucharest plaque was added to this entry January 2023.

Odorheiu Secuiesc and six other towns — Update (January 2023): the Albert Wass bust in Reghin has been removed and the school in Nușeni renamed.

This town’s memorial park has a bust of Albert Wass (1908–1998), Hungarian count, poet and antisemite who served in the Nazi-allied Hungarian army. The likeness is of Wass, but the bust is coyly named “Secuiului ratacitor,” or “The wandering Hungarian,” most likely to skirt Romania’s law prohibiting the public glorification of war criminals.

In Romania, Wass also has a bust in a school courtyard in Lunca Mureșului and another in a church courtyard in Reghin; a park with a memorial stone in Brâncovenești; a memorial plaque outside the Fortified Reformed Church in Sfântu Gheorghe; a memorial outside the Reformed Church in Santăul Mare; and a school in Nușeni. For more Wass monuments, see the Hungary section.

Jimbor and four other towns — Busts of Jòzsef Nyírő (1889–1953) in Jimbor (above left) and Odorheiu Secuiesc (above right). A Hungarian writer and member of the fascist and antisemitic Arrow Cross Party, Nyírő smeared Jews as “well-poisoners” and called for their eradication from Hungary. The reason Nyírő has busts in Romania is that his birthplace in Transylvania belonged to Hungary at the time; later on, it became part of Romania. Hungary’s rehabilitation of Nyírő led to protests from the local Jewish community as well as Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel.

Nyírő also has two plaques in Jimbor; a street in Odorheiu Secuiesc; a street and plaque in Racoș; and schools in Frumoasa and Satu Mare.

For more Nyírő monuments, see the Hungary section.

Note: the entries below were added during the January 2022 project update.

Pitești and four other locales – A street for Nichifor Crainic (1889–1972), yet another ideologue who helped shape the theory of Romanian fascism. “The Jews pose a permanent threat to any nation-state,” wrote Crainic, who served as minister of propaganda in Antonescu’s Romania. He also advocated for the seizure of Jewish property.

Crainic has additional streets in Șelimbăr, Valu lui Traian and Vișan, as well as a plaque in Bucharest. Above right, Jews surrendering property to Romanian authorities.

Mangalia and Segarcea – Mangalia has a street for Vintilă Horia (1915–1992), author, convicted war criminal and compatriot of Nichifor Crainic (see entry above), who served in fascist Romania’s diplomatic mission to Rome. He also has a bust (above right) and school in his hometown of Segarcea.

For more on Romania’s systematic extermination of Jews and Roma see Yad Vashem, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Azrieli Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program and the Washington Post.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO