Nazi collaborator monuments in Hungary

Hitler ally Miklós Horthy has a bust in Budapest, Csókakő, and Kenderes

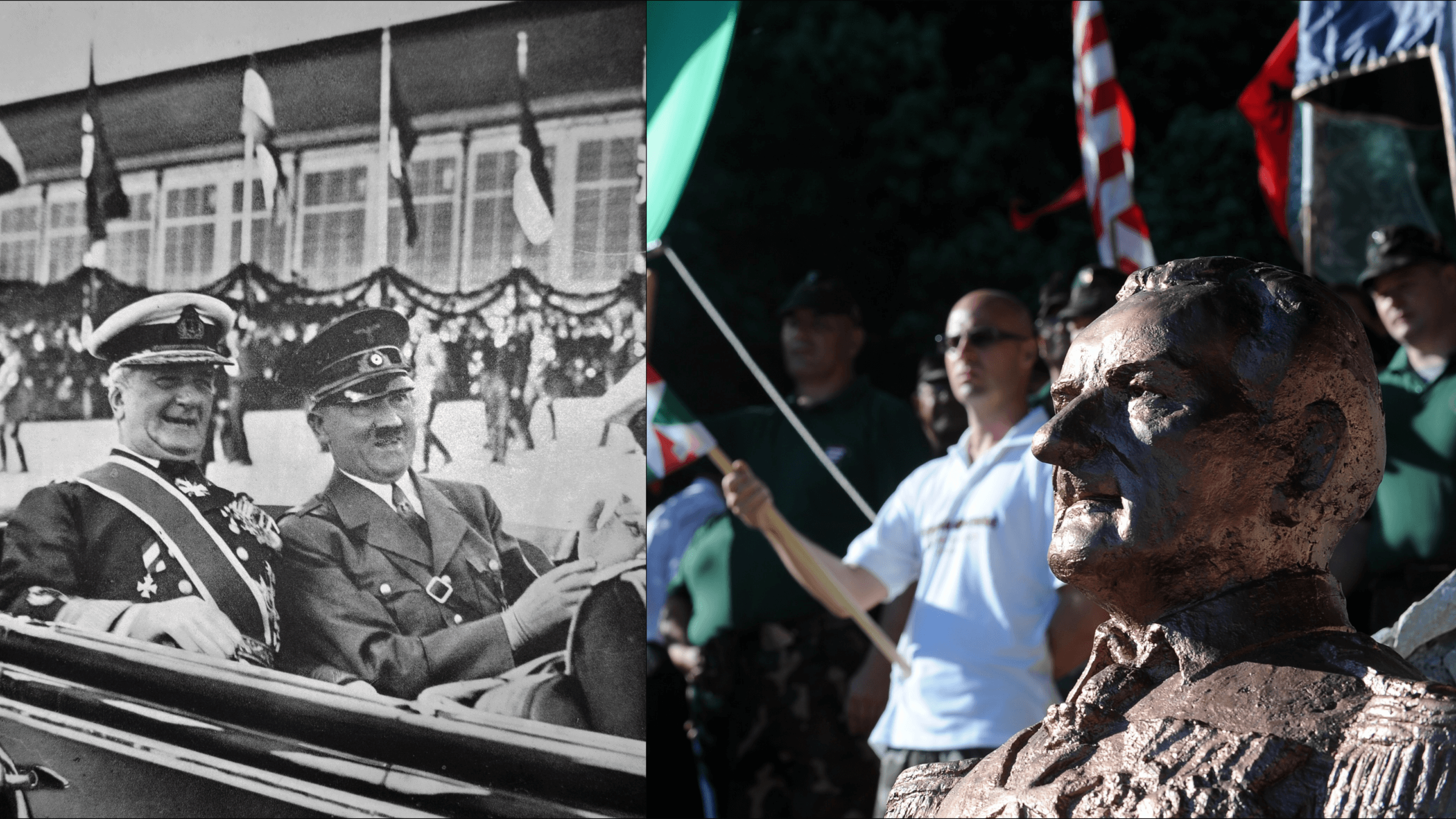

Left: Miklós Horthy with Hitler, 1938 (Wikimedia Commons). Right: far-right rally during unveiling of Horthy bust in Csókakő, June 16, 2012 (Attila Kisbenedek/AFP via Getty Images). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email editorial@forward.com, subject line: Nazi monument project.

Budapest — A bust of Hungarian despot and Hitler ally Miklós Horthy (1868–1957), which was moved into a prominent Budapest location in 2013. The move was condemned by Jewish groups and even the U.S. embassy. Horthy supported and enabled Nazi Germany’s project for the annihilation of his country’s Jews, passing antisemitic legislation similar to the infamous Nuremberg Laws.

In 1941, Hungary deported around 22,000 Jews to Ukraine, where they were killed by German and Ukrainian collaborators. In 1944, Hungary deported 437,402 Jews, mostly to Auschwitz, where the vast majority were exterminated. In total, 568,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Above left, Jews being deported from Kőszeg, 1944.

Budapest has at least three plaques honoring Horthy located on the Military History Institute and Museum; Veres Péter Street; and Szabadság Avenue. A hotel in the city has a Horthy bust as well.

Hungary’s Holocaust distortion has extended to manipulating museums and memorials to recast itself as a blameless victim of WWII. In 2012, Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel returned his Order of Merit, a Hungarian state award, to protest the whitewashing; in 2014, prominent Holocaust scholar Randolph L. Braham, another survivor, followed suit. See reports by the Associated Press and the New York Times.

Csókakő – A bust of Horthy erected 2012. The unveiling ceremony was accompanied by a far-right rally, a common occurrence which happened during debates over the Budapest bust as well. Coverage in Reuters. Hungary’s rehabilitation of Horthy has been condemned by the U.S. government as well as the World Jewish Congress and other Jewish organizations. Above left, Horthy and Hitler in 1938.

Kenderes and 14 other towns — Hungary’s Horthy statues include a bust in Horthy Castle in Kenderes, above left; statues in Kereki (erected in a square named after Horthy), above right, Hajdúbagos (originally erected in the courtyard of the village country house/museum in 2013 and relocated to the main square in 2020) and Hosszúvölgy; busts in Bodaszőlő, Csátalja, Harc, Hencida, Káloz and Szekszárd; and plaques in Lillafüred, Nagymágocs and the Reformed College in Debrecen. Horthy also has streets in Kunhegyes and Páty.

Below, members of the far-right Mi Hazánk (“Our Homeland Movement”) party commemorate the hundred-year anniversary of Horthy taking power in Budapest, March 1, 2020. Horthy, who enjoyed grand spectacle, had entered the city on a pristine white horse like the ones ridden by his modern sympathizers. Two weeks earlier, neo-Nazis from across Europe gathered in Budapest for the “Day of Honor,” an annual rally which uses WWII history to organize and inspire today’s neo-fascists.

Note: The Lillafüred and Nagymágocs plaques were added to this entry in January 2023; the Csátalja and Szekszárd busts were added in August 2023.

***

Baja and 102 other towns — A bust of Albert Wass (1908–1998), Hungarian count, poet and antisemite who served in the Nazi-allied Hungarian army. Wass was awarded the Iron Cross, a Nazi Germany military honor. After the war, he immigrated to the U.S.

Despite being condemned as a Nazi collaborator by the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Hungary’s Jewish communities, Wass wasn’t deported due what the State Department claimed was lack of evidence. This is an all-too-common occurrence among Western governments, which allowed thousands of Nazi collaborators to enter their countries. See the introduction section for more on this.

Wass statues and plaques have been erected all over Hungary. A partial list includes ones in Harkány (below left), Aszód (below right), Alsózsolca, Arnót, Átány, Balatonakarattya, Balatonalmádi, Békés, Békéscsaba, Bonyhád, Budakeszi, Budapest (as well as in District IV, XII and XVII, two in District V, two in District XXI, plaques in District X, XIV and XVI and a square), Csanádpalota, Csemő (and a street), Dabas, Debrecen (and two plaques), Detk (at the Albert Wass Library), two in Eger, Érpatak, Gödöllő, two in Győr, Gyúró, Hajdúnánás (and a street), Harc, Hódmezővásárhely, Jászárokszállás, Kalocsa, Kaposvár, Kapuvár, Kisbér (at the Albert Wass Cultural Center), Kiskunfélegyháza, Leányfalu, Martfű, Mátészalka, Mezo (detail here), Mezőkövesd (at the Albert Wass Memorial Park), Miskolc (and a bust and street), Mohora, Nagyatád, Nyíradony, Nyírmártonfalva, Pákozd, Pálosvörösmart, Pápa, Pécel, Pilisszántó, Pomáz (and a street), Püspökladány, Rátót, Sárospatak, Soltvadkert, Solymár, Sükösd, Szarvas, Százhalombatta, Szeged, Székesfehérvár (and a street), Szendrő, Szentes, Szigliged, Szilsárkány, Szolnok, Szombathely, Taksony, Tapolca, Tiszaföldvár, Tolcsva, Törökbálint, Törökszentmiklós, Várpalota, Verőce (at the Albert Wass Park; there’s also a separate street), Veszprém, Visegrád and Zalaegerszeg.

Wass also has a community center/library in Mikepércs; a library in Ráckeresztúr; a cultural center/library in Sülysáp; a museum in Vác; and streets in Ballószög, Balmazújváros, Bogács, Bükkaranyos, Dunakeszi, Felsőpakony, Felsőzsolca, Fót, Gyál, Győrújfalu, Kunhegyes, Mád, Máriakálnok, Nagykáta, Ócsa, Pécs, Püski, Szatymaz, Szigethalom, Tata, Tetétlen, Tiszakécske, Tököl and Vecsés. His works have been introduced into school curricula as well. See reports in Deutsche Welle and the Jerusalem Post. See the Romania section for more Wass honors.

Note: the Budapest District XII and Pálosvörösmart monuments were added to this entry in January 2023.

Note: the entry below was added during the January 2022 project update.

Kiskunfélegyháza and Kecskemét – A plaque of Jòzsef Nyírő (1889–1953) in the courtyard of the Sándor Petőfi City Library in Kiskunfélegyháza. A poet and prominent member of Hungary’s fascist Arrow Cross Party, Nyírő smeared Jews as “well-poisoners” and called for their eradication from Hungary. He also has an alley in Kecskemét.

Hungary’s rehabilitation of Nyírő, which extends to putting his work in school curricula, led to denunciations from the local Jewish community as well as Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. Above right, Wiesel’s letter returning a Hungarian state award in protest of, among other things, whitewashing of Nyírő.

See the Romania section for Nyírő honors. For the battle over Nyírő glorification, see the short documentary “Nyírő Jòzsef, Szeklers’ Apostle?” by Alexandru Iacob (with English subtitles).

For more on Hungary’s numerous monuments to Hitler’s allies see György Lázár’s list of Horthy statues and monuments in the Hungarian Free Press, Failed Architecture for a good overview of Hungary’s battles of statues, and Defending History’s Hungary page.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO