Banned from YouTube? Welcome to DLive, a safe haven for America’s neo-Nazis

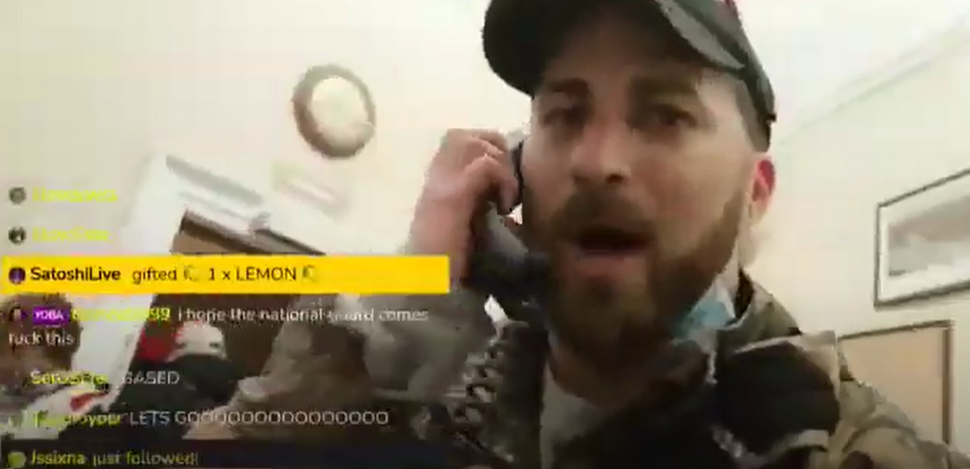

A screenshot of a video of Baked Alaska’s livestream By Molly Boigon

While millions of Americans watched Wednesday’s surreal events unfold on cable news outlets and mainstream media websites, at least 16,000 watched the insurrectionists invade the U.S. Capitol building in real time via livestreams posted by members of the mob themselves. Instead of Norah O’Donnell or Anderson Cooper, their host was a 33-year-old neo-Nazi who has been banned from multiple social-media platforms and narrated the scene with comments like, “Yeah, buddy! 1776, baby!”

These savvy, anonymous internet users tapped into the livestream via a little-known platform called DLive. Normally used for video-game streaming, it has increasingly become home to far-right extremists who have been booted off mainstream networks like YouTube. The host is known on DLive and other platforms as Baked Alaska, but his real name is Tim Gionet, a former BuzzFeed employee who took a hard right turn during the 2016 presidential campaign.

“HEY!” Gionet cried out to his fellow rioters as they broke into an office inside the Capitol. Practically wheezing, he zoomed his lens in on a desktop telephone, and shouted: “Let’s call Trump!”

DLive’s chat feature lit up with encouragement — and hate speech. And, though Gionet has been blocked from Twitter since 2017 because of antisemitic posts, far-right fans screenshotted images from the DLive video and posted them to Twitter throughout the afternoon. (Gionet was also banned from YouTube in October of 2020; his livestream was reposted there Thursday.)

“Sure am glad to be living this in real time with y’all,” one of these fans Tweeted. “Baked Alaska & Co just chilling in a private room inside the Capitol. They’re touring the place.”

That Baked Alaska risked providing law enforcement with video evidence of his crimes in order to gain a broader audience for his antics came as no surprise to experts on far-right extremism and its internet communications ecosystem. But the use of fringe sites like DLive in Wednesday’s insurgency shows the complexity of efforts to to “deplatform” such extremists, or remove them from mainstream sites like Twitter, YouTube and Facebook — they seem to always find a way to get their hateful messages out.

“There has been a cottage industry of these so-called free-speech platforms,” said Oren Segal, vice president of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Extremism. “It’s not hard for extremists to find that alternative.”

Gionet has been on somewhat of a public hiatus since November 2019, when he led a crowd of protesters in heckling Rep. Dan Crenshaw, a Texas Republican, at an Arizona State University event about the benefits of capitalism. They asked him about the 1967 Israeli attack on the USS Liberty and other conspiracies.

He had previously garnered attention from those who track white supremacists during the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, where Gionet was one of many people filmed chanting, “Jews will not replace us,” “Hitler did nothing wrong,” and “I’m proud to be white!”

Gionet, an Alaska native, is a former rapper and social media strategist at BuzzFeed — he was responsible for the Twitter and Instagram accounts for the outlet’s popular food content arm, Tasty. He started to support then-candidate Donald Trump, and slowly moved further and further to the right, quitting BuzzFeed and joining rank with far-right political commentator Milo Yiannopoulos.

Gionet’s return to prominence on DLive is part of broader migration of deplatformed extremists. The CEO of DLive, Charles Wayn, did not reply to requests for comment on Thursday, but the platform issued a statement on Twitter saying it “does not condone illegal activities or violence.”

Other alt-right figures who regularly livestream on DLive after being kicked out of more popular social media networks include Nick Fuentes, a white nationalist closely linked to the alt-right Groyper Army; Patrick Casey of the neo-Nazi group formerly known as Identity Evropa; Matthew Q. Gebert, who led a Washington, D.C. chapter of a white-nationalist organization; and Owen Benjamin, a self-described comedian who said that gay people and Jews “will destroy your entire civilization.” Some make thousands of dollars from their videos, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, paid directly by viewers who like their videos.

Fuentes, for example, who has talked during his livestreams about the “Jewish media attacking your babies,” is making about $119,000 a year on the platform, the SPLC reported. The SPLC did not track Gionet’s earnings, but he has 16,000 followers, compared with Fuentes’ 55,000.

Amy Spitalnick, executive director of Integrity First for America, the nonprofit behind a lawsuit challenging the organizers of the Charlottesville rally, said Wednesday’s events show that current pushes to deplatform people from Facebook, Twitter and YouTube do not go far enough.

The companies responsible for registering and managing domain names and web-hosting entities like those associated with DLive need to refuse to work with extremists.

Some activist groups, like Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, have targeted registrars for hateful websites like VDARE, but registrars and hosts are nearly invisible to the public and pressure campaigns are rare.

In any case, she said, President Donald Trump’s broad reach on Twitter and Facebook and loyal base dampen the impact of deplatforming any other individuals.

(Trump was barred from Twitter for 12 hours on Wednesday and by Facebook on Thursday for two weeks — more time than remains in his presidency — because of posts including threats and election misinformation violated their rules.)

“When you have the president and those in the highest levels of government inciting and encouraging this violence, it undermines efforts to deplatform these extremists and that is a factor that is harder to control,” said Spitalnick.

Though Wednesday’s events show the loopholes in deplatforming extremists, experts said it’s still an important tool limiting their reach. YouTube has 2 billion monthly active users, compared to the 5 million on DLive, so pushing hateful actors to those fringe platforms inevitably reduces the number of eyeballs on their content.

But the ADL’s Segal said that the “spectacle” Americans saw on Wednesday could “broaden the base of people who might be interested” in seeking out extremist views on such smaller platforms.

The images livestreamed on DLive and disseminated through other means were designed to be inflammatory and shareable. The extremists wore outrageous costumes and took selfies with their feet up on lawmakers’ desks.

The images project an image of boldness and pride. The very fact of having been deplatformed from mainstream sites, experts said, also sometimes enhances an extremist’s following on the underground ones, where they are seen as martyrs.

That effect was seen on Thursday as the news spread that Gionet had deleted a replay of the Capitol livestream from his DLive channel, and a rumor circulated that he had been arrested.

“Love you baked,” said one commenter. “Any go fund or bail bond post it asap,” referring to a GoFundMe, a crowdsourced fundraising website.

“Name a more oppressed group than trump supporters,” said another.

Lisa Kaplan, founder of the Alethea Group, which helps organizations navigate online threats, said that members of organized hate groups will use the images and videos to recruit new members and show their strength. And, she warned, they also might have further reach.

“We can anticipate this being used in propaganda against the United States by our foreign adversaries,” she said.

Correction, January 8, 9:59 a.m.: A previous version of this story misspelled the Alethea Group.

Molly Boigon is an investigative reporter at the Forward. Contact her at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @MollyBoigon.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO