Amid coronavirus, Brazilian Jews face rising anti-Semitism

Rabbi Ventura speaks with young men who posted racist messages on Facebook in Fortaleza. Image by Courtesy Eduardo Campos Lima

A conspiracy theory linking the novel coronavirus outbreak to Jews has been tied to a succession of anti-Semitic incidents over the past few months in Brazil. The cases have prompted a swift and concerted response from Jewish activists there.

A March 14 Brazilian Facebook post blaming Jews for the plague and said Jews desired to “take revenge against civilization.” Image by Courtesy Eduardo Campos Lima

On March 14, a Facebook page dedicated to the work of Sigmund Freud posted a small text signed by its manager, Luís Olímpio Ferraz Melo, denying the Holocaust and blaming the Jews for the plague of the Middle Ages. The Jews desired to, “take revenge against civilization,” wrote Melo, after being enslaved in Egypt and have been “using the fallacious Holocaust to pose as victims.”

“The ‘swine flu’ (H1N1) has been proved to have been programmed by and beneficial to the Jewish group Rockefeller,” Melo wrote.

The author added, falsely, that “no Jew” has been documented with coronavirus anywhere in the world. “Therefore one must pay attention to such incontrovertible historical fact,” Melo wrote, stoking the conspiracy with a flat-out lie. Melo’s post received more than a thousand comments, many of them critical.

Jewish leaders and institutions have been quick in repudiating such comments. In Sao Paulo, where about 50,000 of Brazil’s estimated 107,000 Jews live, Rabbi Gilberto Ventura mobilized members of his synagogue for a protest against Melo’s Facebook post. The Brazilian Israelite Confederation (known as Conib, in Portuguese) prepared to take legal measures against him. Such actions, however, had to be postponed, due to the social distancing measures applied in Brazil since the pandemic reached the country.

Trivializing the Holocaust

Other recent occurrences have also provoked Jewish concerns, trivializing the Holocaust and signaling what many fear is a deterioration of the sociopolitical atmosphere.

On April 8, Marcos de Morais, the host of a news show on SBT, a major TV station in Brazil, affirmed that people infected with the novel coronavirus should be taken to “concentration camps of health care, with more sophisticated equipments, with the best professionals.”

His comment spurred outrage among the Jewish community. Silvio Santos, SBT’s owner – who is Jewish – announced his suspension for 15 days.

The Holocaust Museum of Curitiba instantly published a repudiation of TV host Morais’ comments. “That was the most visualized Facebook post we had since the foundation of the Museum, eight years ago. More than 700,000 people have seen it,” the Museum director Carlos Reiss said.

The institution wished to stress the fact that the problem with Morais’ comment was not only the use of the term “concentration camps,” but the eugenicist idea behind it. “The idea of taking out of society and confining the sick and the ones seen as ‘aberrations’ is typical of the Nazi T4 Program,” Reiss added. “The Museum was going to protest such comment even if he hadn’t directly mention concentration camps.”

On the same day, Allan dos Santos, a blogger and supporter of President Jair Bolsonaro’s policies, made an allusion to the murder of Jews in Nazi Germany during a debate on Twitter on the benefits of chloroquine in the treatment of Covid-19. The substance has been presented almost as a miraculous solution by President Bolsonaro, as it has by President Donald Trump.

“To omit the use of chloroquine is the same as leaving Jews in doubt between a shower and a gas chamber,” Santos twitted.

Conib has published a repudiation letter, and said it’s going to take legal measures against Santos.

In the opinion of Conib’s president Fernando Lottenberg, the Brazilian judicial system doesn’t unconditionally support free speech. “Many decisions of the Supreme Court established the understanding that hate speech cannot be tolerated in any circumstance. That’s our legal tradition in Brazil,” Lottenberg said.

Rising populism sparks concerns

Lottenberg believes that the occurrence of such incidents is related to the rise of populist leaders who foment a less democratic atmosphere. In Brazil, the election of President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 was a culminating point in a cycle of distrust in democracy, said Reiss.

Indeed, pre-coronavirus there was an escalation of intolerance in the country. The most serious occurrence took place in the city of Jaguariúna, in São Paulo State, in February. A 57-year old man was walking on the street wearing a kippah when he was surrounded by three men who shouted racial slurs. The men severely beat him, breaking his dental prosthesis, and tore up his kippah with a knife. According to a police report, one of the aggressors said to the victim that “Hitler’s only mistake was that he didn’t kill more people.”

In different occasions, men were spotted wearing swastika armbands. That display has been a crime in the country since 1989.

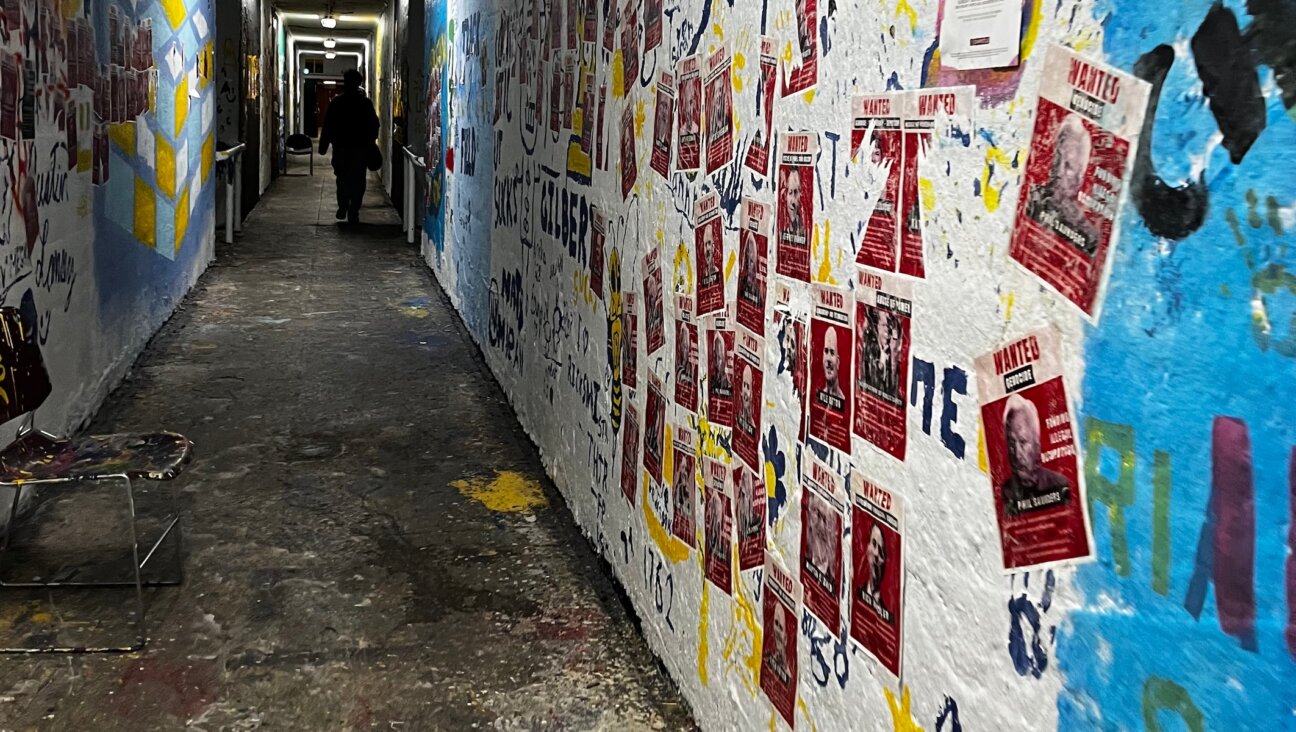

In January, a group of four young men posted on Facebook a series of racist messages against the Jewish community in the Northeastern State of Ceará. The police identified all authors of those comments and they’re now facing charges of racism and threat.

The most notorious anti-Semitic episode happened on January 16, when President Jair Bolsonaro’s then-Secretary of Culture Roberto Alvim released a video to announce the creation of a new arts funding program. Alvim’s speech contained several similarities with a speech given by Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels in 1933. The video’s background music was Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, a work famously praised by Hitler.

Alvim’s video spurred outrage among the Jewish community and the Brazilian society as a whole. He was fired by Bolsonaro on the following day.

From Sao Paulo, Rabbi Ventura has led the struggle against each one of those cases. He campaigned for the opening of an investigation on Alvim’s video and for his dismissal, and was asked by the federal government to help it develop anti-racist actions.

He was also the first Jewish leader to get in touch with the Jaguariúna victim and made his case public. A few days after the attack, he organized a motorcycle rally with all attendants wearing kippahs, with the help of Jewish members of the most famous motorcycle club in the country.

That was an initiative to draw visibility to the issue and to the Brazilian Jews, he said. “Brazilians in general have very inaccurate ideas about Jews. We have to show the people another image in order to build a new dialogue.”

In the case of Fortaleza, Rabbi Ventura’s denouncement of the hate messages on Facebook prompted State authorities to call him shortly after. He then suggested an encounter with the authors of the posts and they agreed to meet with him.

A specialist in the history of the Bnei Anussim, the descendants of Iberian Jews who were forced to convert to Catholicism in the 15th and 16th centuries and were sent to colonial Brazil, Rabbi Ventura was asked by the State Secretary of Public Security, who was present at the meeting, to tell the young men about the Jewish roots of the Northeast region of Brazil.

“I told them about the several Jewish cultural habits that the people still have in that region and they suddenly identified with that history. They began to ask me questions about it with vivid interest. At the end, they all apologized and hugged me,” Rabbi Ventura said. The group still faces charges, but their case must benefit from their consent to meet with the Jewish leader.

Dialogue against ignorance

One of the main causes of the Brazilian anti-Semitism is a general ignorance about the Jews, Rabbi Ventura said. With uninformed people the best approach is dialogue, he said. “We have to develop a popular movement and to be present on the streets,” Ventura affirmed.

His Sinagoga sem Fronteiras (Synagogue Without Borders, known as SSF in Brazil) is based on such idea. With branches in several Brazilian States, the movement gathers not only Ashkenazi and Sefaradi Jews who are members of families that migrated to Brazil in the 20th century. There are also hundreds of people who identify as Bnei Anussim and find in the SSF a way of returning to their origins. “We have in our movement people from all social classes and of all colors,” he defined.

One of the participants of SSF is the lawyer and human rights professor Daniela Hruschka Bahdur. On her paternal side, her family is Polish Jew, but had long converted to Catholicism; her mother’s family is Bnei Anussim. Since she recovered her Jewish identity, some old acquaintances began to ignore her. “Brazilians tend to have a stereotypical view of Jews,” she said.

According to José Luiz Goldfarb, director of Jewish Culture and of the synagogue of the Clube Hebraica in São Paulo, there’s a growing consciousness among the community on the seriousness of the present conjuncture.

“We have been exhibiting movies about the Holocaust for years in our cinema festivals and I used to hear people criticizing such choice as ‘excessive’. Now nobody would say such thing,” he said.

São Paulo State Legislator Damaris Moura recently formed a Parliamentary Bloc in Defense of Religious Freedom with the goal of creating public policies to deal with religious violence. “At the moment, I’m discussing with Rabbi Ventura the possibility of creating a specific law to deal with anti-Semitism,” she said.

Moura said most of her work involves educational initiatives. “With a bigger sense of their rights, people have been more active in denouncing racist and anti-religious acts lately,” she added.

Meanwhile, Jewish leaders as Rabbi Ventura will keep working to raise consciousness about the problem. “I’m gathering more and more people to organize the necessary resistance,” Rabbi Ventura said.

Eduardo Campos Lima is a journalist in Brazil.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO