Meet the Man Who Tweets From Auschwitz — the Museum, That Is

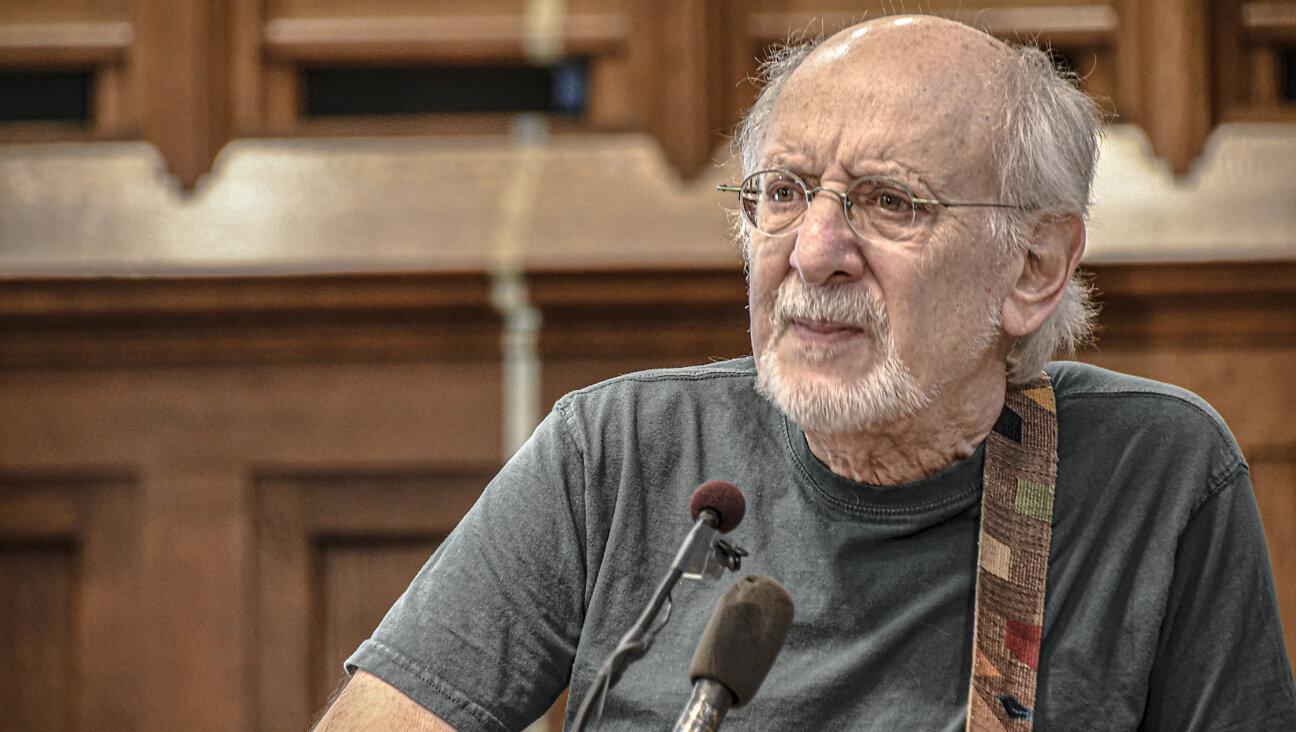

(JTA) — Long before he moved here to become the spokesman for the Auschwitz museum and lead its social media effort, Pawel Sawicki’s life was intricately connected to this sleepy town near Krakow.

A Warsaw-area journalist for Polish Radio 2, Sawicki used to visit Oswiecim as a boy on holidays to stay with his grandparents and play with his cousins, who had moved to the town shortly after World War II.

When he was 10, Sawicki learned that Auschwitz was an epicenter of the Nazi genocide against the Jews — he gleaned the details from a book about the camp that he found in his grandparents’ home.

“Most people visiting Oswiecim, especially from outside of Poland, are shocked to discover there’s a town next to the former German Nazi camp, the memorial which they come to visit. For me it was somehow the other way around,” Sawicki said.

That realization, he said, sparked an interest that led him here a decade ago as a reporter — and it consumes him to this day.

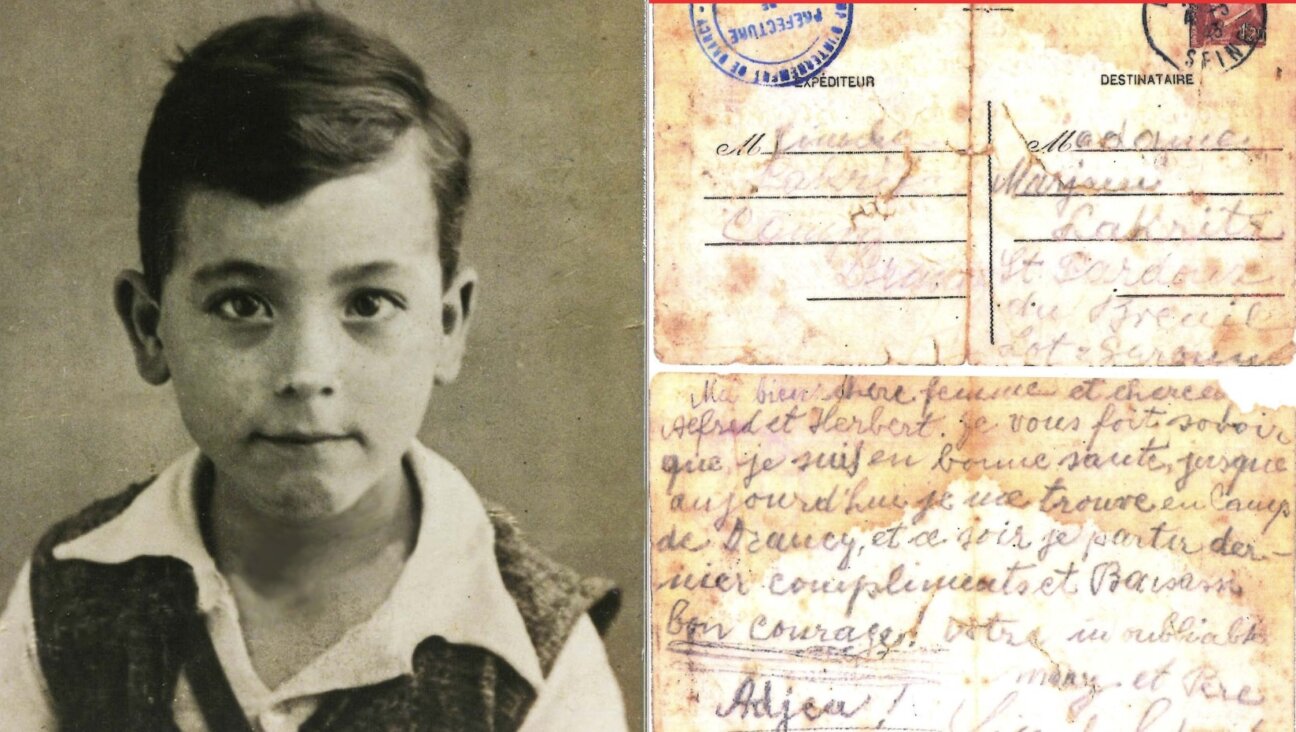

Image by Getty Images

This initial connection to the history of Auschwitz was the beginning of a “constant presence in my life that kept sending me to look for more information,” said Sawicki, 36, who began working at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in 2007. Sawicki has encyclopedic knowledge about Auschwitz, which he has shared in countless articles, guided tours, and several radio and video documentary productions.

But the advent of social media has highlighted another role fulfilled by his office: as “a shield protecting the memory of victims” against rampant abuse online, he said.

A case in point was Sawicki’s intervention last month on Twitter when he called out Kurt Schlichter, a columnist for the conservative news site Townhall, for writing that Jewish supporters of Barack Obama and John Kerry “would have made a fine helper at Auschwitz.”

After some deliberation, Sawicki decided to tweet Schlichter’s message on the Auschwitz memorial account, adding: “The tragedy of prisoners of Auschwitz and their complicated moral dilemmas which today we can hardly comprehend should not be instrumentalized.”

With 40,000 likes and retweets, it became the memorial’s most retweeted message ever, topping the one about Pope Francis’ visit in July and exposing Schlichter to withering criticism.

This reach and intense reaction demonstrate the reasons for Sawicki’s careful consideration on whether to intervene, he said.

“In some cases, such actions risk offering a platform to abuse, thereby amplifying it,” he said. “But exposing and correcting such behavior can have a positive effect that sometimes justifies this risk. But it’s always a fine balance.”

The overwhelming rejection by Twitter users shows that calling Schlichter on his words was the right move, said Sawicki, whose office once was the pharmacy of the SS troops serving in Auschwitz.

But he does not engage Holocaust mockers and deniers as a matter of policy.

Sawicki has also demanded corrections from journalists who apply the word “Polish” to death and concentration camps built by Nazi Germans on Polish soil; doing so is a felony in Poland. And the museum will seek apologies or corrections from those who note that the camps are in Poland without adding that they were built under Nazi occupation.

But much of the online activity of the museum is to highlight positive examples of online engagement with Auschwitz, in Polish, German, English and other languages. There are regular “this day in history” tweets, links to articles and comments from recent visitors (“Where was man?” asks one), and news articles referring to Auschwitz and Holocaust commemoration. Earlier this week there were photos of the camp under a blanket of snow with the message: “New year brought snow which changes the landscape of the historical site.”

On the ground, the museum’s task is to safeguard the buildings and environs and to gather, study and publish evidence on German atrocities. But online, “our main goal is to provide education on the scale of the crime and what made it possible,” Sawicki said.

The Nazis murdered more than 1.1 million Jews at Auschwitz as well as 70,000 non-Jewish Poles, 25,000 Roma, and some 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war.

“Our social media policy is an extension of our guidelines as an institution, but it is developing week by week because we’ve never had such direct interaction with so many people,” Sawicki said. It’s both a chance to “educate people from all corners of the world, many of whom will never be able to visit the memorial.”

But abuse online is also a growing problem.

Amid a renewed wave of interest in the Holocaust in recent years in films, books and other media, as well as in visits to the museum – it registered a record of more than 2 million entries last year — the “instrumentalization,” trivialization and denial of the Holocaust has been growing as well, Sawicki said.

“It’s a daily, fast-changing challenge,” he said.

At the museum, Sawicki navigates the institution’s 470 acres with certainty, demonstrating an intimate knowledge of almost all aspects of life — and death — here. Unlike some visiting guides who resort to pathos or sanctimony, Sawicki, wearing a colorful scarf that his mother-in-law made for him, shares in an informal but precise manner illustrative facts and anecdotes that he has spent a decade collecting.

At the Death Wall, an execution site that is located in the yard adjacent to Block 11 in Auschwitz I, Sawicki dryly explains to a group of journalists that around the wall there was sand mixed with sawdust designed to drain blood.

“Some testimonies mentioned that an adult male bleeds about two liters [67 ounces] when shot, so on days with dozens of executions this place was quite literally soaked in blood,” he said.

Sawicki once interviewed a survivor who recalled laughing at the sight of a fellow prisoner wrestling free from under cadavers that had collapsed on him from a cart. SS guards also laughed. Such testimony illustrated to Sawicki the complexities of surviving at Auschwitz, “but also the amazing human personal strength” doing so required, he said.

While most of the hundreds of thousands of people who visit Oswiecim annually likely associate it with death and horror rather than a town with 900 years of history, for Sawicki it is also the place where he started a family after moving in 2007 with his wife, Agnieszka, whom he married while living here. His son, Wojtech, attends kindergarten near here.

For Sawicki, the town’s dark history is no impediment to loving it.

“It has always been a second home to me, and now it is even more so,” said Sawicki, who grew up in the quiet Warsaw suburb of Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki. “We have to accept these aspects of history in Poland and strive to make a better future.”

Agnieszka, however, has had a tougher time acclimating “because she’s a real city person, a Warsaw girl who needed some time to get used to the different pace,” Sawicki said.

The couple have told their son neither about the Holocaust nor about his father’s workplace except to say that it’s a museum.

“We don’t want to introduce it before he’s ready to take it in,” Sawicki said. “So we’re kind of waiting for him to ask the questions.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO