Will Stabbing Attack Tear Apart Israel’s LGBT Community?

Image by iStock

When an ultra-Orthodox fanatic named Yishai Schlissel stabbed six people at the Jerusalem Gay Pride march in July — 16-year-old Shira Banki later died of her wounds — Schlissel also fractured Israel’s self-image as a global beacon for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights.

For years, Israeli diplomats have used their country’s impressive record on LGBT issues to score political points on the world stage. But the picture they painted was of Tel Aviv, the so-called gay capital of the Middle East, with its gay and lesbian bars and beaches, and miles of rainbow bunting unfurled ahead of the raucous annual pride parade. Forty miles to the east, Jerusalem’s gay community feels like a stifled minority.

As the broad LGBT movement in Israel takes stock of the attack, the differences between the two societies has come to the fore. Three days after the stabbing, Tel Aviv activists declined to travel to Jerusalem to protest the violence, instead staging a separate rally in Tel Aviv’s Gan Meir park. The Tel Avivians had already planned a memorial service that evening to coincide with the six year anniversary of a fatal shooting at a local gay youth center. But Jerusalemites still felt stung by the decision.

“When this happened the expectation was that everyone would drop everything and come and be in solidarity in Jerusalem,” said Tom Canning, spokesman of the Jerusalem Open House for Pride and Tolerance. “We wouldn’t be our small group of hundreds of activists, we would be our group of activists with thousands behind us. There was a strong sense of disappointment, I would even say disbelief, that [Tel Avivians] were deciding to go ahead with their own event.”

Tel Aviv’s rally drew major politicians, with impassioned speeches by Zionist Union chairman Isaac Herzog and Yesh Atid chairman Yair Lapid. Though President Reuven Rivlin spoke at the Jerusalem protest, activists there bemoaned the disunity between the two communities that they said feeds into Tel Aviv’s image as the only safe haven for gays in Israel.

“The Tel Aviv-based organizations are giving hand to creating and strengthening an LGBT ghetto in Tel Aviv,” said Canning.

The gay rights movement in Israel has its roots in Tel Aviv in the 1970s, with the founding of the national Israeli Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Association, known as the Agudah. One of the first public pride events took place in Kings of Israel Square, now known as Rabin Square, in the Tel Aviv city center.

In the 1990s, the fledgling movement was buoyed by a “legal revolution,” Hebrew University of Jerusalem professor Alon Harel wrote in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review. Within a few short years, the Knesset banned workplace discrimination against gay people , the Israel Defense Forces ensured their equal treatment — 19 years before the United States army did the same — and, following a high court order, El Al airlines began giving free tickets to the partners of gay employees.

Then, in 2009, a gunman entered a Tel Aviv gay youth center and opened fire, killing two. Six years later, the perpetrator has still not been found. The attack traumatized LGBT Israelis, but it also sparked a national conversation about their rights. Today, Tel Aviv’s gay community is central to the city’s identity and politics. Even politicians from the right, such as Likud minister Miri Regev, have appeared at the city’s gay pride parade, which drew 100,000 Israelis and tourists in 2015. Contrast that to Jerusalem, where only left and center-left politicians show up, and marchers typically number only about 5,000.

For Tel Aviv’s well-established LGBT community, the next frontier is same-sex marriage. But while legalizing gay marriage would benefit all Israelis, it’s a distant priority for gay people in Jerusalem, who are focused on survival.

“There are two voices here,” said Sattath. “One is the voice of Tel Aviv that seeks freedom of marriage, like in the United States, and that is a very difficult goal to achieve, but it is a valid goal. The other voice is that of Jerusalem. The majority of gay Jerusalemites are so oppressed that they can’t even dream of marriage; they need education and societal change.”

Jerusalem’s activists say that they face a combination of municipal neglect and incitement from ultra-Orthodox rabbis and politicians who see their parade as an “abomination.” Jewish Home Knesset member Betzalel Yoel Smotrich even took to Facebook after the stabbing to call the parade an “attempt to besmirch traditional Jewish family values.”

“The message for years has been that we are desecrating the holy city of Jerusalem,” said Canning. “People say, ‘It’s horrible that someone stabbed us and attacked us, but why you are you doing this in Jerusalem?’”

On the official level, Jerusalem’s LGBT community has had to fight its way to recognition. For years, the Jerusalem municipality refused to fund the Jerusalem Open House, even though it provided services to thousands of Jerusalemites and thus was entitled to public support. In 2010, after years of legal wrangling, the high court ordered the municipality to pay $120,000 to the Open House in .

The seemingly careless policing of Pride — Schlissel had recently been let out of prison for carrying out a similar attack on the same march in 2005 — only heightened the feelings of vulnerability among gay Jerusalemites.

Jerusalem’s LGBT activists say that education is the key to acceptance in their city and beyond. According to Sattath, all secular schools in Israel have the option to include an LGBT-themed curriculum. But she wants it to be a central component of Israeli education rather than an add-on. Eventually she would like to see LGBT issues addressed in Orthodox and Arab schools as well.

“Extremists have to be nourished somewhere, and they are nourished by a society that ignores us and silences us, and where homophobia is very, very prevalent,” she said.

Sattath said that she has been buoyed by the solidarity of other Israelis. Many showed support by changing their Facebook photos to a rainbow flag with a candle. Two Israeli celebrities — Labor politician Itzik Shmuli, of Lod, and Tel Aviv journalist Keren Neubach — publicly came out after the stabbing. But Orthodox gay Israelis in places like Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh found themselves burrowing deeper into the closet.

“[The stabbing] has created an atmosphere in which people are afraid to tell the truth to tell their families, their close friends,” said Ron Yosef, founder of Hod, an organization for Orthodox gay men and lesbians.

In Jerusalem there is a feeling that LGBT leaders have no choice but to work within the city’s conservative culture to change religious attitudes about their existence. In Tel Aviv, on the other hand, activists are vigilant about politicians trying to score political points at the expense of their community. Naftali Bennett, a minister from the ultranationalist Jewish Home party, was turned away from the Tel Aviv solidarity rally when he refused to sign a document to advance gay rights in Israel. Bennett’s party opposes gay marriage in Israel.

Jerusalem activists, by contrast, opted against such a litmus test at their own rally.

“This was in order to allow everyone from the entire political spectrum and the religious spectrum to come and speak freely against homophobia and violence,” Canning said. “We didn’t want to turn this into a political event.” Bennett chose not to attend the rally in Jerusalem.

After the protests, Tel Aviv activists made a belated gesture toward Jerusalem when the Agudah chartered a bus to Jerusalem for a vigil for Banki, the victim of the stabbing attack.

And some Tel Aviv activists are acknowledging it’s time to look past the Tel Aviv “ghetto” to Jerusalem as the new battleground for gay rights.

“The real fight is in Jerusalem,” said Mickey Gitzin, a Tel Aviv city council member and gay activist. “Many times our opponents want to keep us in the ‘ghetto’ in Tel Aviv. They say, ‘This is your city, stay there.’ But we are here, we are everywhere, and it is time for us to speak up.”

Contact Naomi Zeveloff at [email protected] or on Twitter, @naomizeveloff

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

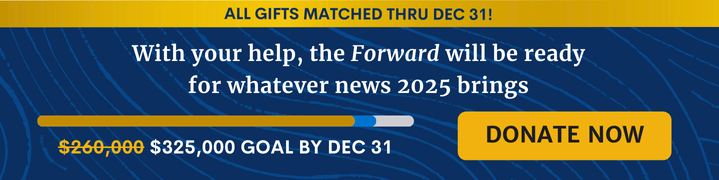

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $325,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO