Classic Jewish Novels Trace a Community’s History

While much of America is busy these days reading about Harry — Harry Potter, that is — I’ve been spending much of my summer reacquainting myself with Sonya, Marjorie and Alexander — Sonya Vrunsky, Marjorie Morgenstern and Alexander Portnoy, that is — the fictional protagonists of “Salome of the Tenements” (1923), “Marjorie Morningstar” (1955) and “Portnoy’s Complaint” (1969), respectively. This trio of American Jewish classics sheds a great deal of light on the evolution of American Jewish letters, as well as on the history of the American Jewish community. They make for awfully good reading, too.

Take “Salome of the Tenements,” for instance. Written by Anzia Yezierska, the so-called “Cinderella of the sweatshops,” this cautionary tale of an immigrant Jewish woman lusting in equal measure after beauty, status and a well-born non-Jewish man (“one of America’s noblemen”) absorbed readers’ attention when first published. A real potboiler, it offered a behind-the-scenes look at the immigrant experience on the Lower East Side — and from a woman’s perspective at that. While critics found Yezierska’s language nothing if not “vivid,” a word that appeared time and time again in their reviews, contemporary readers may find it clumsy and overwrought. But no matter. The yarn she told was a good one. It even had a happy ending: Disenchanted by her gentile husband, Sonya leaves him for Jacques Hollins, né Jaky Solomon, a co-religionist with an equally fine-tuned sense of aesthetics.

The book was published at a time when the United States was in the last throes of “Salomania,” its fascination with all things Salome, from sexy silent films about the biblical character to salacious plays and dances. Although its title at first blush seems a trifle odd and discordant — Salome of the tenements? — it works once you factor in the larger cultural climate. This story was, after all, Yezierska’s attempt to offer her very own take, a much more redemptive take than most, on the popular story of female sexuality run amok.

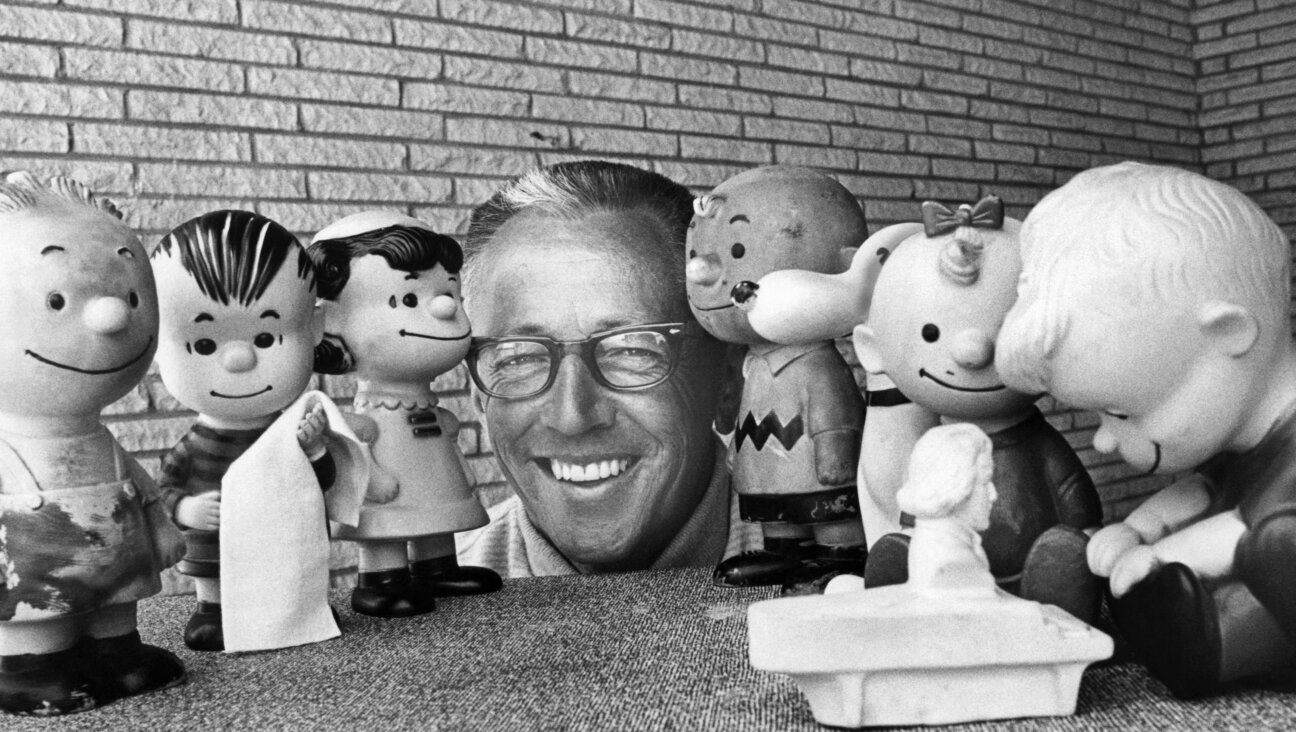

Sex — or, more to the point, its avoidance — also loomed large in Herman Wouk’s best seller “Marjorie Morningstar,” a familiar presence on the bookshelves of many middle-class Jewish homes in postwar America. A Book-of-the-Month Club selection, it recounted at a stately pace the various efforts of a well-heeled American Jewish woman to define herself as an aspiring actress and determined bohemian before settling comfortably into the life of a suburban housewife. Set on the Upper West Side, that “gilded ghetto” of the interwar years, “Marjorie Morningstar” depicted American Jewish life as a normative, middle-class phenomenon rather than an exotic, Old Worldly import, as it figured in Yezierska’s writings. That, and its account of post-adolescent female yearning, touched a nerve, especially among women readers.

The critics, though, were not terribly enthusiastic. Some criticized the book’s length (it exceeded 500 pages), claiming that Marjorie was a “virgin on the verge” for too much of it. Others felt that young Marjorie was no match for Captain Queeg, the intriguing character at the heart of Wouk’s earlier triumph, “The Caine Mutiny.” “I can only admit that Marjorie and her 565 page journey from mediocrity to mediocrity left me baffled and unimpressed,” opined William DuBois of The New York Times.

The critics notwithstanding, the popularity of “Marjorie Morningstar” put Wouk on the cover of Time magazine in September 1955, where his fidelity to tradition, to Jewish ritual observance, was the subject of sustained description. The best-selling author, it was dutifully reported, not only grew up in the Bronx and on the Upper West Side, but also kept kosher, observed the Sabbath and even was given to eating gefilte fish on Friday night. Gefilte fish, the magazine explained for the benefit of its readers, consisted of “balls of chopped fish, egg, onion and seasoning, boiled with vegetables.”

Were that not enough to concretize Wouk and his world in the mind of America, Time also featured a map, “Wouk’s West Side,” which highlighted several of the Manhattan sites that figured prominently in “Marjorie Morningstar,” from the El Dorado apartment building on Central Park West and the Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue to a synagogue just off of West End Avenue. When it came to rendering America’s Jews, fiction and reality, it seemed, went hand in hand.

That said, nothing, absolutely nothing prepared the general reading public for Philip Roth’s explosive “Portnoy’s Complaint,” which chronicled the misadventures of a foul-mouthed, sex-crazed, guilt-ridden and wholly unlikable American Jewish male of the 1960s named Alexander Portnoy. There was no point in expecting softhearted encomia or stirring affirmations of Judaism from him for Portnoy blamed his parents and their Jewish worldview for his own inadequacies. “The very first distinction I learned from you, I’m sure, was not night and day or hot and cold, but goyische and Jewish!.…oh, how I hate you for your Jewish narrow-minded minds!” he cries out. And yet, Portnoy could not shake free of them or, for that matter, of the culture to which they — and ultimately, he — were bound.

The book’s transgressive sexuality, no-holds-barred approach to American Jewish life, freewheeling use of curse words and unredeemable protagonist stunned both readers and critics, giving rise to a torrent of words not unlike those that spilled from Portnoy’s mouth as he bared his soul to his confessor, psychiatrist O. Spielvogel. The must-read book of 1969, it was denounced from the pulpit, exalted by the critics (for the most part) and discussed by just about everyone else.

To some of its detractors, “Portnoy’s Complaint” resembled nothing so much as an antisemitic tract. “This is the book for which all anti-Semites have been praying,” Hebrew University scholar Gershom Scholem declared categorically , insisting that it “provides authentic evidence of Jewish perfidy.” Still other detractors, such as literary critic Irving Howe, dismissed the book as an “assemblage of gags.” Worse still, in a series of deeply wounding asides, Howe characterized Roth as a comedian rather than a writer, and as a morally deficient human being, to boot. “The cruelest thing anyone can do with ‘Portnoy’s Complaint,’” Howe wrote witheringly, “is to read it twice.”

Most book reviewers, however, strongly disagreed. “Portnoy’s Complaint,” cheered The New Yorker, is “one of the dirtiest books ever published. It is also one of the funniest. From first to last, it is unremittingly revolting and hilarious — a single, hysterical howl of excrementitious anguish, at which, uncannily, we are invited to laugh. What is more uncanny is that we actually do laugh.” Other critics praised the book for its unrestrained show of exuberance and irreverence, and for the way it captured the rhythms of Jewish life at the grass roots. Or, as Anatole Broyard put it, writing in The New Republic, “Halfway between Oy! and Wow!, [‘Portnoy’s Complaint’] proves that the Jew is just as good a jerk, just as magnificently and mysteriously irrational, as any goy.” So there. Irrevocably changing what and how American Jews wrote about themselves, “Portnoy’s Complaint” remains in print, its capacity to shock still intact.

Whether taken on their own or as a collective entity, Sonya, Marjorie and Alexander make clear that American Jewish culture and those who swear by it are certainly worth writing about. Harry Potter, make room!

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO