Corruption Looms Large as Israeli Campaign Begins

TEL AVIV — The recent conviction of Prime Minister Sharon’s most trusted political confidant — his son Omri — is dragging the long-festering issue of government corruption into the Israeli election campaign.

Just minutes before the prime minister officially registered his new Kadima party last week, he directed aides to strike his son’s name and signature from the list of founders. By all accounts, the decision was driven by Omri Sharon’s guilty plea in connection to several charges related to the financing of his father’s 1999 primary campaign for Likud leadership.

In an apparent bid to capitalize on the issue, Sharon’s top challenger, new Labor Party leader Amir Peretz, announced Monday that he was naming a respected lawmaker and ex-general, Matan Vilnai, to head the party’s anti-corruption task force. The Shinui Party also has made fighting corruption a centerpiece of its campaign for the March 2006 elections.

To head off any political damage on the issue, Sharon’s camp is highlighting the support of two of Israel’s most respected political figures, Justice Minister Tzipi Livni and one of her predecessors, Dan Meridor, several observers said.

The political jockeying comes after a flood of media reports about shady political appointments, overseas junkets by Knesset members and other alleged misdeeds. The various allegations appear to have reinforced the growing view that official corruption has reached unprecedented heights.

Separate polls taken by Ma’ariv and Yediot Aharonot in recent months have found that a majority of Israelis think corruption is the greatest threat facing the country, even more dangerous than terrorism. Another survey, released last week, found that Israelis see Omri Sharon as the most corrupt member of Knesset and his father as the fifth-most-corrupt minister. Peretz, on the other hand, was viewed as one of the five least-corrupt members of the 120-person Knesset.

Despite such findings, a recent Yediot poll found Sharon’s new party finishing first, with 33 seats, and Labor finishing second, with 26; in addition, Sharon continues to register as the country’s most popular and, tellingly, its most trusted political leader. But his popularity rating has dropped about 10 percentage points in the past year, and some observers are arguing that eruption of a major new corruption scandal is one of the few developments that could short-circuit Sharon’s re-election bid.

Israel’s newly appointed state comptroller, Micha Lindenstrauss, seems intent on keeping the corruption issue on the front burner. Appointed in July, he already has issued reports exposing seven distinct political corruption scandals, including full disclosure of suspects’ names — an unprecedented step in comptroller studies.

“Corruption within government must be wiped out,” the new comptroller told a press conference this month. “I am making this my first priority.” One of his aides said, “This is only the beginning of the measures the new state comptroller intends to take against the spreading of corruption in Israel.”

This past May, outgoing comptroller Eliezer Goldberg delivered a withering verdict on the culture of cronyism and corruption in the government, warning that it threatened the fabric of the state.

Other former Israeli officials are issuing similar warnings. “Corruption is more dangerous than terror,” said Uzi Dayan, former head of Israel’s National Security Council and president of the Sderot Conference for Society, where the recent poll on corruption was released.

In a recent opinion essay in Ha’aretz, former Israeli supreme court justice Yitzhak Zamir warned: “Throughout the history of mankind, large powers have collapsed due to corruption. In Israel, which is having difficulty coping with severe security, social and economic problems, the danger of corruption is especially great.”

International watchdogs, which measure nations’ perceptions of corruption, rate Israel relatively high, but falling. In the annual survey conducted by Transparency International, a European-based monitor that measures attitudes toward corruption in 159 countries, Israel dropped from 14th place to 28th during the past nine years.

Last summer a new initiative to fight corruption was launched in the Knesset, after Likud lawmaker Michael Eitan managed to secure enough votes to establish an inquiry committee to probe government graft. “We sense deterioration in Israel’s proper public administration,” Eitan, a longtime anti-corruption fighter, told the Forward. “Corruption as [a] social phenomenon is growing not only in the Knesset, but is also seeping into other areas. People want to succeed at any cost while trampling rules and regulations.”

In its first meeting, Eitan’s committee decided to examine whether enforcement bodies — including police, the state prosecutor’s office, the court system, trading authorities and other agencies dealing with the business community — were up to the task of combating corruption. But with the country now facing elections, the committee has decided to suspend its activities. Eitan told committee members last Sunday that he fears any mention of corruption would be interpreted as politically motivated. “The committee will pass the data it has gathered in its short period of operation to the next Knesset,” Eitan said to the Forward. “We will pass it along, with a draft of a bill that would give the committee broader powers.”

Eitan said that politicians are currently using the issue of corruption to tar their rivals in advance of the elections, but have displayed no true dedication to fighting public graft.

Twice in Israeli history, mounting public frustration over corruption is believed to have played a key role in driving the ruling party from power. First, in 1977, Likud used the anti-Labor slogan “We’re sick of corruption” to take power for the first time, after it was revealed that the wife of then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin had violated the law by secretly maintaining an illegal bank account in Washington. Fifteen years later, Labor used the same slogan to seize the reins back from the Likud, after a state comptroller’s report raised corruption allegations against several key Likud members.

This time around, following Omri Sharon’s guilty plea, the prime minister and his advisers are working to repair any damage to his image.

The younger Sharon’s lawyers announced November 23 that their client plans to retire from politics, a step seen as an effort to mitigate the sentence and send a reassuring message to the public. The various violations of which he was convicted include the fictitious registration of corporate documents, which carries a maximum five-year term; lying under oath, and violations of the election code. According to the indictment, Sharon — who ran his father’s September 1999 Likud leadership primary campaign — secured $1.2 million in campaign financing from corporations in Israel and abroad between July 1999 and February 2000. Prosecutors said the total far exceeded the legal caps on campaign fund raising. Foreign donations are illegal.

Although the prime minister was not indicted in the campaign finance scandal that brought down his son, the constant media coverage of the affair has damaged his image. Nor is it the only scandal that has plagued his tenure. Other scandals featured allegations of influence peddling and bribery, notably a long-running case involving his other son, Gilad, who is said to have tried to use his father’s influence to advance a real estate deal on a Greek island. The so-called Greek Island case was dropped last June by the attorney general, Menachem Mazuz, citing lack of evidence, despite the chief prosecutor’s recommendation to indict the Sharons.

With such clouds hovering over his family’s head, Sharon opted not to have his son Omri, by all accounts his closest confidant, listed as a founder of the new Kadima party. As it turned out, the Knesset member who ended up filing the party’s slate, Ruhama Avraham, had come under public scrutiny four weeks ago when the state comptroller revealed that the private agriculture export company Agrexco covered all its expenses for a 2004 trip to Belgium and the United States.

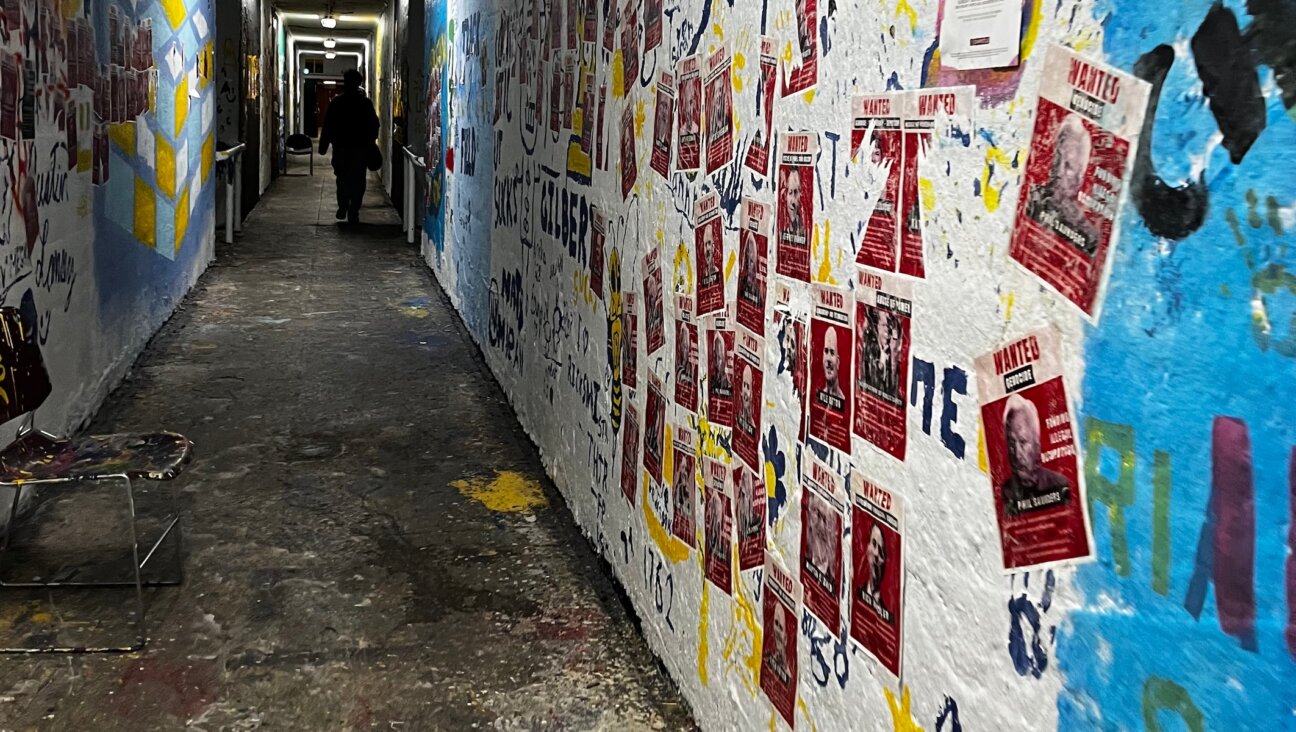

Right-wing activists who opposed Sharon’s disengagement plan have attempted to draw public attention to the various family scandals in an effort to discredit his government and the Gaza pullout.

Sharon’s political opponents also have been hit with corruption allegations. Tzahi Hanegbi, now acting Likud chairman, was forced to resign last year as public security minister, in charge of the national police, while police probed allegations that he appointed dozens of political allies to posts during an earlier term as environment minister. The investigation is still underway.

Peretz, the newly elected Labor leader, also has found himself on the defensive. Haim Ramon, who recently quit Labor and joined Sharon’s new party, accused Peretz last week of using union funds and facilities to promote his own political career after taking over the Histadrut trade-union federation. Ramon, who preceded Peretz as Histadrut chief, accused Peretz of appointing loyalists to key posts without the consent of the union plenum. During his campaign for Labor leadership, Peretz was accused by opponents of falsifying the signatures of thousands of new party members.

Even the Shinui Party, so far the only party to announce that it would make fighting corruption a major platform in its upcoming campaign, has found itself in the middle of controversy. One party lawmaker, Yosef Paritzky, was forced to resign as infrastructure minister last year after it was revealed that he tried to smear a party colleague in the run-up to primary elections.

“Serving the public for over 40 years, I have encountered every existing kind of corruption and even some that nobody ever heard of before,” said gadfly lawmaker Yossi Sarid of the left-wing Meretz Party. “Corruption is a matter of culture. It is deeply embedded in the Israeli society. No law or directive could fight it and win. It all derives from education and the responsibility of the state for its future citizens’ moral values.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO