Encountering a Nazi Relic in Odessa’s Fabled Tunnels

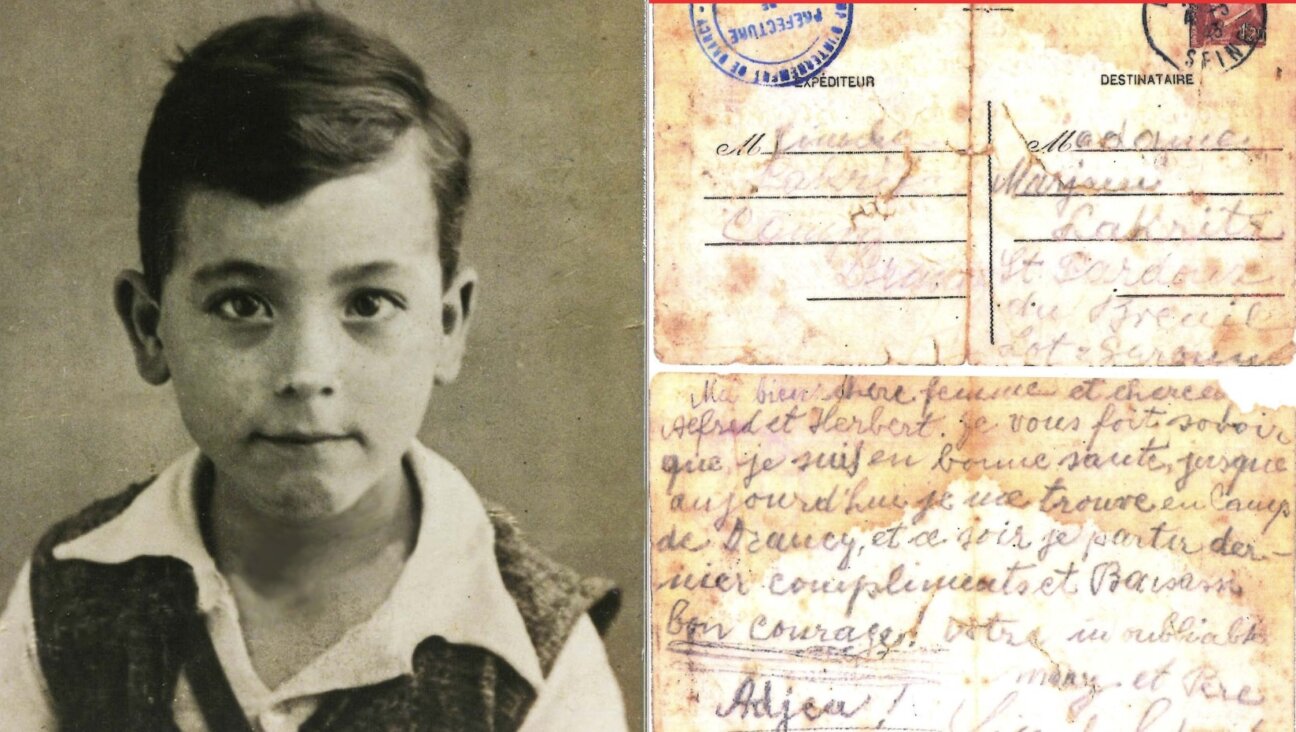

Beneath the Surface: Odessa is home to over 1,000 miles of underground limestone tunnels; at one time this section was used as a bomb shelter. Image by Steve Duncan

Odessa, as a city, reminds me of no place more than New Orleans. It’s not the geography or architecture of these two cities, it’s the similarity of character and of their place in the greater pantheon of the cities of their respective regions of the world.

Like New Orleans, Odessa isn’t a capital. It isn’t even one of the larger cities in the country. Its citizens are by and large poor, its economy not the greatest. Its best days are obviously about 150 years behind it. Yet it’s still full of character, can still hold its own on a cultural level with towns that far outpace its population and economy. “Oh, yes — everyone knows that the funniest comedians/baddest gangsters/best writers are from Odessa” is a constant refrain there.

And of course, among these superlatives can be included “longest tunnels.” The city lies in a region that has no natural forests, and as a result the limestone of the surrounding area is the main building material and has been continually quarried for about 200 years. The result is a sprawling, mostly unmapped series of tunnels spreading out from the center of Odessa. The network is gigantic: well over 1,000 miles of abandoned stone quarries that have taken on the colloquial name of “the catacombs.” This is why I’m here, and it’s where I make a surprising discovery.

Over the past few years I’ve been to a lot of places, in a lot of cities, where your average tourist shouldn’t be — and many more that your average tourist doesn’t even know exist. I’ve discovered ancient Roman ruins in the sewers beneath the Capitoline Hill, dodged trains and the third rail in five of the 10 largest subway systems in the world, managed to avoid entrance charges for landmarks from Stonehenge to the Pyramids to Notre Dame.

That last one didn’t end so well: After climbing the Cathedral, I was caught and arrested when, for some reason, I decided I had to ring the bell.

I’ve become part of the world of people who break into national monuments for fun, put on movie screenings in storm drains and travel the globe, sleeping in centuries-old catacombs and abandoned Soviet relics rather than in hotels and bed-and-breakfasts. I’ve partied with people living in the tunnels under New York, squatters in an abandoned São Paulo mansion, and now Ukrainians in the Cold War bunkers and partisan hideouts under Odessa.

The Ukrainians I’m with could be anyone at first glance. They don’t really look the part of “urban explorers,” which is what the members of the loose-knit worldwide network of artists, historians, adventurers and other assorted nutcases are sometimes called.

But then again, nobody I’ve met in this world has really looked the part. Not the shy Korean girl from a wealthy family who takes naked pictures of herself in abandoned power plants. Not the London bus driver with a weakness for lager, mince pies and well-endowed women, who is halfway to his goal of visiting every abandoned subway station on earth. Not the flamenco dancer with the soft Quebecois accent who travels the world, rappelling into storm drains.

And certainly not me, a mild-mannered Midwestern Jewish boy who got nervous sneaking cigarettes between classes in high school.

Supplies in tow, we drive out to one of the small towns that surround Odessa. It’s the middle of the day, and there’s no need to be clandestine about where we’re going. This is one of the few things I’ve done that’s not actually, technically, illegal. But it’s certainly not encouraged. This network is raw, and incredibly labyrinthine. People get lost in the tunnels all the time. Luckily, the people I’m with are the closest thing to professionals that exist: They’re actually whom the police call if they get reports of someone lost in the catacombs. Unfortunately, sometimes all they end up finding is a body.

We spend hours in the catacombs, doing several trips to various sections. We get used to this world, and happily wander the tunnels underground, eating, drinking, drinking some more and learning how to swear in Russian. But our trip isn’t just a big party. The catacombs have a history to them, a history that, when you experience it up close and personal, is haunting.

First we come to a cavern with several names written in Cyrillic on the wall, which my Ukrainian guides explain are the names of a group of partisans who hid in the quarries while fighting the fascist occupation: Odessa was under occupation by the Axis powers from October 1941 to April 1944. During this occupation, the catacombs were used as a base for several groups of these fighters, who numbered about 300 overall. There’s an official museum in part of the catacombs that’s dedicated to this history (in true Soviet fashion, it’s called the Museum of Partisan Glory) in the village of Nerubayskoye — not too far away from where we are — but it’s a tiny part of the overall network.

Continuing, we see plenty of other remnants of this time: old weapons, bullets, bottles, graffiti and, most heartbreakingly, a cavern where one of the walls is painted to represent a bedroom, with windows, furniture and a plant growing in a pot on the windowsill. And then we turn a corner and see, carved into the limestone wall, a circle about a foot in diameter with a swastika carved into it.

My first thought is that this isn’t real; wasn’t actually carved by Nazis; was instead inscribed later, by some punk. This is reinforced by my remembrance that Odessa was occupied mainly by the Romanians during World War II, with Nazi Germany being involved only sporadically after the initial victory. And it’s further reinforced by something else I’ve run into, which is the unbelievable amount of neo-Nazi graffiti in Eastern Europe. And it wasn’t just on the street: I found it in the underground, too, in hillside drainage tunnels in Kiev and in a utility network in Moscow.

On all my travels, everywhere, I’ve held open the possibility that I’ll run into, as us American Semites put it, fellow “members of the tribe.” My favorite thing about being Jewish is the internationalism, the sense that you’re part of some vague worldwide crew. It’s difficult even to put that on paper, as it brings up images of old anti-Semitic canards of secret cabals and quests for global domination.

But there is something to the bond that’s shared simply by being Jewish, even if you don’t otherwise share a country, language, ethnicity or really even a religion. Jews are the most internationalistic people in the history of humanity, which is the primary reason they have always been among the first targets of nationalist movements, turning to nationalism themselves only in a last-ditch attempt at survival after almost 2,000 years of rejecting it.

It’s not just the fact that there have been settled Jewish communities in almost every nation on earth, although history, and the 20th century in particular, has seen the extinction of dozens of them. During my travels, expatriates I’ve run into — or even random backpackers — have all seemed to be disproportionately Jewish. It seems like my people are just comfortable being on the road, rarely averse to rolling into new and unfamiliar locales. I have always wondered how much of my wanderlust was in the blood, part of the tradition passed down ever since Moses, my eponymous predecessor, led his 40-year migration.

Compounding this possibility, Odessa is one of the most Jewish cities in Eastern Europe, despite the community being decimated during the Holocaust, and with most of the surviving community immigrating to the United States after the fall of communism. And many urban explorers, as a rule, have much of that same wanderlust, that same curiosity, that I’ve noticed in my brethren. I always half expect there to be this overlap when I meet new explorers abroad. As such, I would not have been at all surprised to hear a few Yiddishisms escape from the mouths of any of the people we were with.

But here there’s also a strange inversion to this possibility. In my time in Eastern Europe, I gathered that being a neo-Nazi might be something that’s extreme, sure, not in the mainstream, yet not so entirely beyond the pale that it’s a social death sentence, something that you just aren’t allowed to espouse in public.

My best analogy is that being a neo-Nazi in Eastern Europe is akin to something along the lines of being one of the members of the Westboro Baptist Church, in America, the ones that hold up the “God Hates Fags” signs. Someone whose views are taken as extreme, out of the mainstream political consensus, but still people who aren’t afraid of being seen on camera espousing these views (and are definitely not adverse to writing them on the wall of an abandoned limestone quarry). One Russian urban explorer, whose tagline read, “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for the white race,” even tried to friend me on Facebook.

As a result, I’ve been a little wary about the people I’ve met. Not suspicious exactly, but just as “Maybe the people we meet will turn out to be Jewish” has

been put into the category of “within the realm of possibility” in my head, “Maybe the people we meet will turn out to be neo-Nazis” been transferred there from its previous home of “something that would make a bad episode of ‘Seinfeld,’” as well.

I look at the carving on the wall for a while, and my companions catch me staring. I relay my skepticism about the authenticity of the carving, suggesting that it was probably neo-Nazi locals who carved it. But my companions insist otherwise.

“No, that is from the war,” they tell me. “There are other ones in here. They all look the same.”

More than any other modern regime, Nazi Germany has been thoroughly discredited, its historical imprint wiped from current existence. In Italy you can still run across buildings whose keystone reads “built during the XIVth year of the Fascist regime.” In the United States there’s a Tennessee state park named for the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. But there is no place in the entirety of Europe where the government would allow a Nazi relic to be displayed openly, at least not outside the confines of a museum, without a very good explanation for it.

This carving was one of the rarest things a person could find. Even in a former German bunker we had found in the tunnels under Paris, built during the Nazi occupation of the city, there was nothing past the words Notausgang (Emergency Exit) and Rauchen Verboten (No Smoking) on the walls. Much of the purpose, the excitement, in urban exploration is finding this kind of thing, a historical remnant preserved because of the remoteness and inaccessibility of the location. I’ve gotten to see something incredibly rare. My emotions are telling me differently, but my head says I should leave it as is, leave it for others to experience, to have their own thoughts and feelings upon its discovery. After all, ideologically the Nazis have been universally debunked and destroyed. There is nothing left to fight, the victory long since complete.

And if I were someone different, had a different family with a different history, I would have likely heeded this thought and left it alone. And if another, different person had made this choice, I would have understood, made no judgments.

But I’m not a different person. To me, these people aren’t a vague historical ideology, just a symbol and an epithet now. All I can think of when I look at the carving in the stone is that whoever put it there wanted to murder my whole family.

I pick up a piece of glass, dig it into the soft limestone surrounding it and start to hack away. I don’t stop to think about what the others will think of it. After a few moments, one of the Ukrainians, a gruff black-haired man who doesn’t speak English, gets up, takes out his pocketknife and joins me in my erasure.

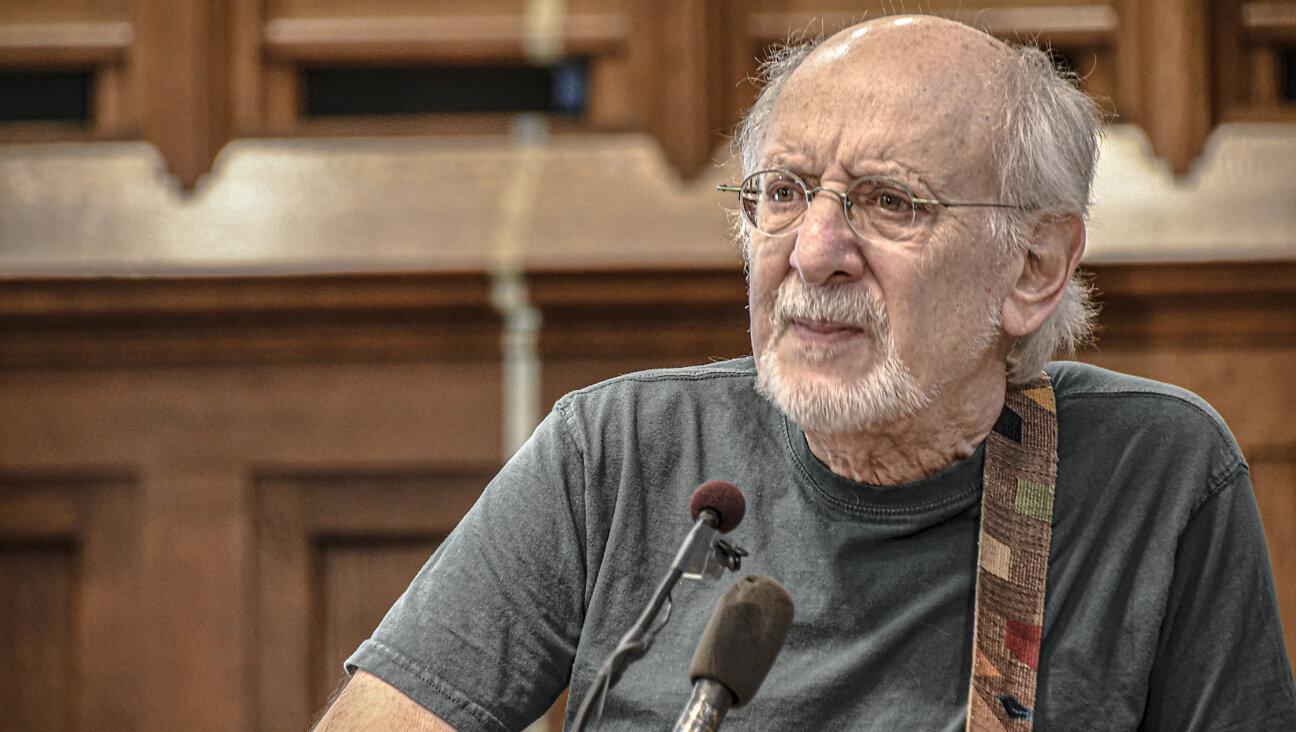

Excerpted from “Hidden Cities: Travels to the Secret Corners of the World’s Great Metropolises; A Memoir of Urban Exploration” by Moses Gates, with the permission of Tarcher/Penguin, a member of Penguin Group USA. Copyright 2013 by Moses Gates. Visit Moses at MosesGates.com.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO