Summers of Love At a Bungalow Colony

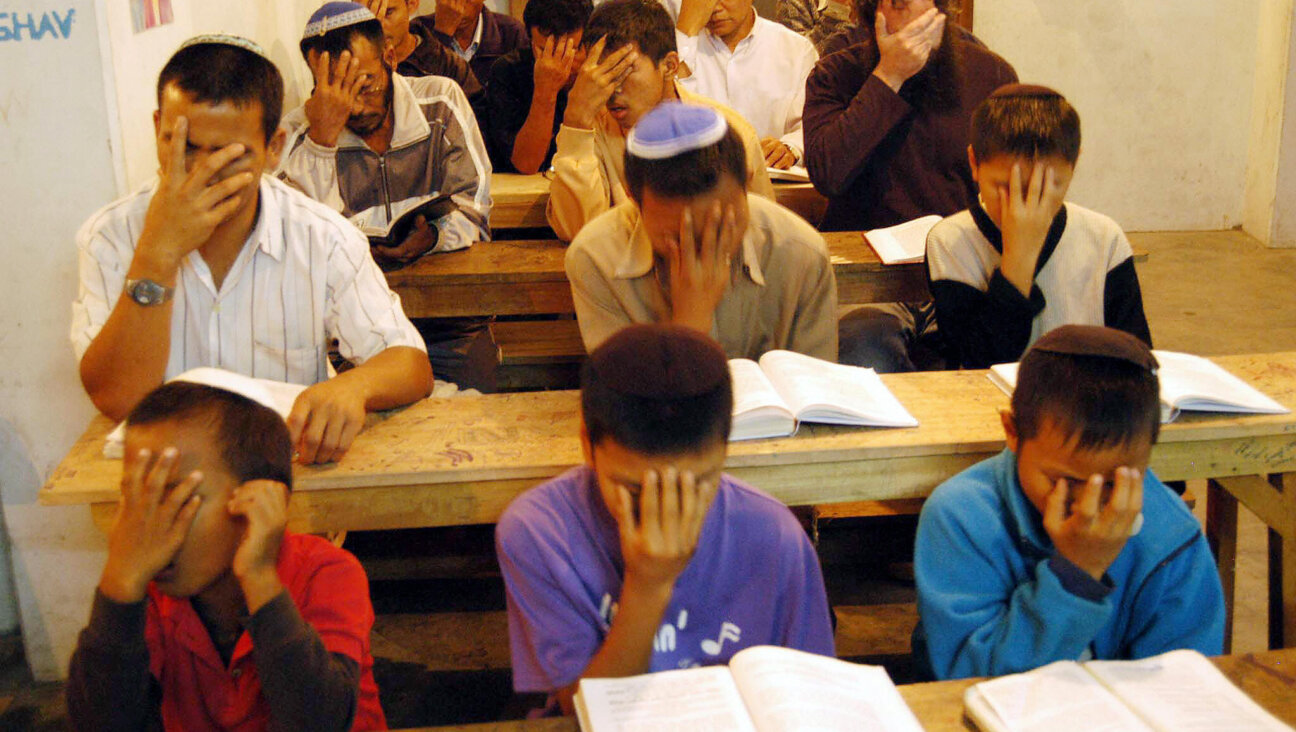

Reminiscing: Many of the teenagers pictured above who spent the summer of 1970 at the Rosmarins bungalow colony returned this year for a reunion. Image by COURTESY OF SCOTT ROSMARIN

‘You! You look great! Let’s take a picture! We all still look the same!”

Reminiscing: Many of the teenagers pictured above who spent the summer of 1970 at the Rosmarins bungalow colony returned this year for a reunion. Image by COURTESY OF SCOTT ROSMARIN

Really? Thirty or 40 years after they last met as spades-addicted teens, and they still look the same?

Well, maybe they do — to each other. Maybe all it takes is meeting up again at the same bungalow colony and seeing the same old luncheonette, the same handball wall, even some of the same families at the pool (sitting in what may well be some of the same lounge chairs). Maybe when you see all that, the faces of long-ago friends look the same, too. At least that’s what happened a few weekends ago, at the 69-year-old Rosmarins bungalow colony, still miraculously alive, well and unchanged, in Monroe, N.Y.

It’s the bungalow colony where I spend my summers, too. But I’m a newbie — I only arrived in 2001, as an adult. This reunion was for people in their 40s and 50s who’d spent their summers there as kids. Thanks to modern miracles like Facebook, e-mail and the occasional stent, about 75 of these folks were planning to get together at a Manhattan restaurant in the middle of winter when Scott Rosmarin, the third generation of his family to run the colony, said (electronically): “Wait! Why not come up here, where it all started, in the summer?”

So they did. And they stayed for 12 hours, through drizzle and sun, from lunch right on through that Catskills staple: a floorshow in the “casino” — barn, that is — complete with singer, comedian and jokes. (Some of those were from 40 years ago, too.) Mostly, though, folks just talked.

“I remember everyone cramming into my bungalow to watch the moon walk,” said Norman Schulman, now a real estate developer in Parkland, Fla.

“Beads! We lived for those little beads. They came in tubes….”sighed Lori Koonin, a Long Island mother of four.

Robin Molho, now a risk manager living in Manhattan, recalled, “When you were taking a shower and your neighbor turned on the water, you knew” — because suddenly the shower turned freezing. (Still happens, I informed her.) But most of the memories hinged on something far warmer: romance.

“I remember I was 16, and I said to my parents, ‘This is going to be my last summer here,’ and then all of a sudden, it was like the heavens opened up, and there were 20 guys coming down the street,” Randy Schonfeld said. She told her parents she’d changed her mind. Good thing, because she ended up marrying one of those guys (sent, it turns out, not directly from heaven, but by the closing of another bungalow colony).

“I must’ve fallen in love 12 times,” recalled Pete Grossman, a writer now living in Westchester County, N.Y. And when it wasn’t love, he added, it was its close relative. “I can remember going: ‘Oh my God! Oh my God! Oh my God!’ just to see a bikini strap,” he said. “It’s a good thing we had athletics.” In fact, they even had a teen bowling team back then. (Still do, I told him.) “I won ‘Most Improved Bowler’ one year,” Grossman boasted. “And I don’t think I’ve improved since.”

But back to romance.

Thanks to the “Brigadoon”-like quality of the colony, kids — even teens — were (and are) allowed almost unheard-of license.

“We’d come back from the teen group” — an evening trip to the movies, or the aforementioned bowling league, for instance — “and we’d all run off the bus to the sundeck to play spades,” said Rona Schulman, now a stay-at-home mom in Columbia, Md. “We’d sit there till 2 or 3 a.m. Our parents knew where we were.”

But did the parents know what they were doing?

“We’d play spin the bottle,” Norman, her brother, piped up. “Or seven minutes in heaven.” (Don’t ask!)

“Those were the happiest days of my life,” said Rockland County, N.Y., advertising agency owner Jayne Koonin, not caring how trite she sounded. “We bathed in that freedom.”

Nonetheless, that is not what most of them are bathing their own children in now. While some families renting bungalows at Rosmarins have three or, in one case, even four generations up here together, most of the reunion-goers have moved on, however wistfully.

“I understand why people would come here if they lived in an apartment, but when you have a house and a backyard, it’s hard to justify,” said David Tratner, 41, a publicist who lives on Long Island. “I used to love to do this, but I don’t know if it makes sense.”

Summers today, like the rest of the seasons, tend to be much less communal: Every backyard for itself. Summers are also more structured. There are specialty camps and internships and a lot of dual-income families where neither parent can spare time away from the office. And there’s also the sneaking suspicion that freedom itself is — wrong. Unproductive. Dangerous.

And yet, everyone at the reunion was longing for it. “There were no cars, no streets, no play dates, no enrichment. They went outside to play,” said Joyce Tratner, David’s mother, who also attended the reunion. “The mothers didn’t have enrichment, either. We just played, too.”

As the Tratners were reminiscing, David’s 4-year-old daughter wandered off to a big grassy field, and David, suddenly noticing this, dashed off after her, despite the fact that there are still no cars on the property, no strangers, no danger. The girl kept running farther and farther away, laughing.

It’s that feeling that everyone at the reunion had come to recapture.

The laughing part, that is.

Lenore Skenazy is the founder of www.freerangekids.com and author of “Free-Range Kids: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts with Worry)” (Jossey-Bass, 2009).

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO