Yosef Yerushalmi, 77, Polymath Historian

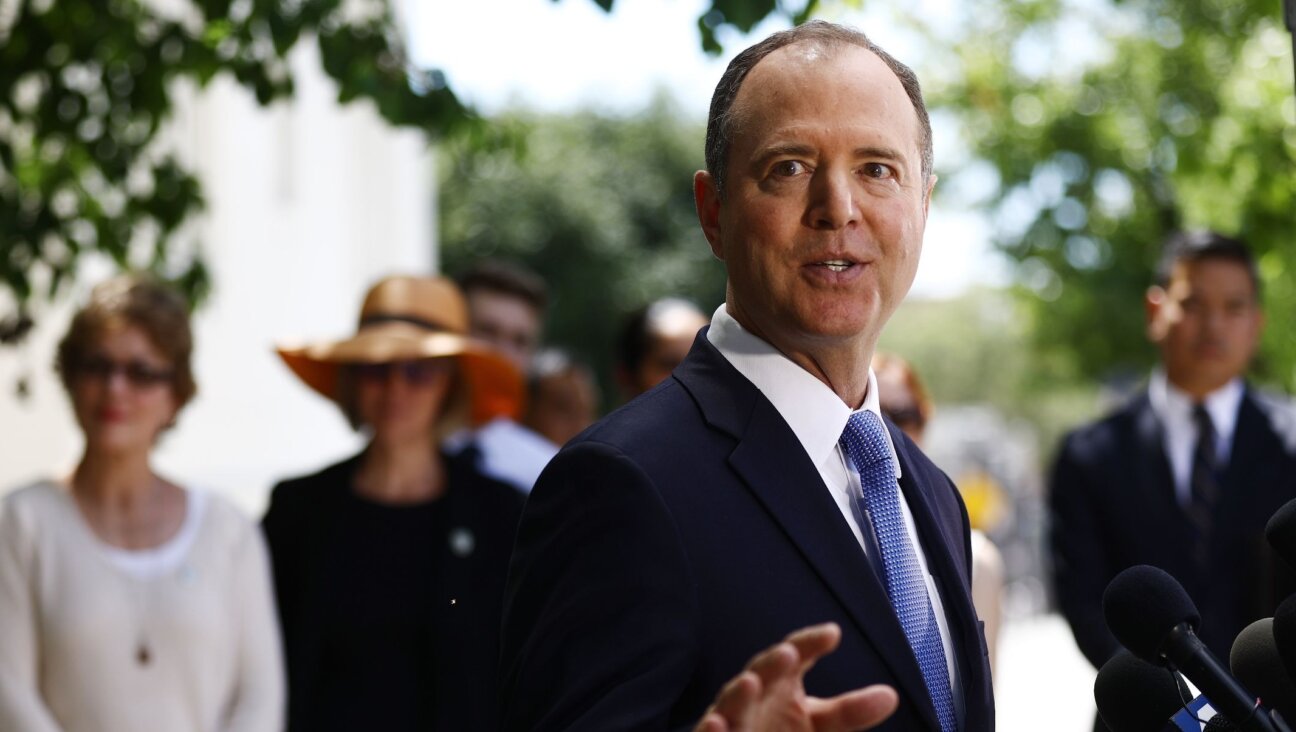

Encompassing Mind: Yosef Yerushalmi ruled over Jewish his- tory from his perch at Columbia University. Image by FILE PHOTO

The world of Jewish studies lost a towering figure on December 8 with the death of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi at the age of 77. Yerushalmi was arguably the leading scholar of Jewish history in the post-Holocaust age, renowned for his rare combination of erudition, analytical brilliance, and literary elegance. His wide-ranging studies left a profound imprint on a generation of students, over whom he presided with a unique Old World authority. But his work also resonated with a wider lay readership in this country, Europe, and Israel, for whom he translated often-arcane scholarly questions into central issues of contemporary identity.

Yosef Yerushalmi inherited the mantle of leadership in the field of Jewish history from his teacher, the legendary Salo Wittmayer Baron, with whom he studied and whose name adorned the chair that Yerushalmi held at Columbia University from 1980 to 2008.Unlike Baron, who authored scores of books, including the 21-volume “Social and Religious History of the Jews,” Yerushalmi wrote relatively few. But each of his works was a masterpiece of scholarship, the product of a meticulous, profound, and at times tortured writing process.

The effect was never a merely dispassionate historical description, but a creative inquiry into the past that resonated powerfully in the present. At the core of all of Yerushalmi’s work, from his first book on a Spanish converso to his last major study on Sigmund Freud, was a deeply personal fascination with the multiple and often competing strands of identity that constituted the modern Jew.

Born in the Bronx in 1932, Yerushalmi was raised in a home in which Hebrew and Yiddish were spoken alongside English. He received a traditional yeshiva education that afforded him an intimate familiarity with the classical sources of Judaism. Yerushalmi had an insatiable appetite for general culture, and developed as a young man an abiding passion for European literature, languages, and classical music. He received his B.A. at Yeshiva College (1953) and rabbinical ordination at the Jewish Theological Seminary (1957), after which he briefly served as a congregational rabbi.

Unsatisfied with pulpit life, he commenced doctoral studies with Salo Baron at Columbia, writing his dissertation on Isaac Cardoso, a 17th-century Spanish-Catholic intellectual and court physician who came to recognize his Jewish roots and abandoned his comfortable life in Madrid to live openly as a Jew in Italy. Based on massive research and written with novelistic verve, the dissertation became Yerushalmi’s first, award-winning book, “From Spanish Court to Italian Ghetto” (1970). On the basis of his dissertation, Yerushalmi was invited to teach at Harvard University in 1966, where he remained for 14 years and held the Jacob E. Safra Chair in Jewish History and Sephardic Civilization before leaving for Columbia in 1980.

In his early career, Yerushalmi established himself as a leading scholar of Iberian Jewish history. Yet it was a measure of his restless mind and personality that he moved far from Iberia in his subsequent work. His rare capacity to traverse the entire terrain of Jewish history was evident in “Haggadah and History” (1975), a large and handsome survey of some 200 Haggadot that revealed the diverse forms and surprising malleability of the central Passover liturgy.

Yerushalmi’s greatest contribution as a scholar, however, came in “Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory” (1982). This short volume not only covered — with characteristic erudition and lyrical grandeur — a vast historical time span; it essentially invented a new discourse in the field of Jewish studies: the discourse of history and memory. In the first three chapters of “Zakhor,” Yerushalmi discussed the ritual practices and texts that Jews used prior to the 19th century to forge a rich web of collective memory. That web was undone, he argued in the fourth chapter, by the new project of critical history, which dispassionately dissects the past rather than revering it. Indeed, history in its modern guise had become “the faith of the fallen Jew.” Beholden to history and yet detached from memory, the modern Jew was irretrievably caught between worlds.

The influence of “Zakhor” was enormous. The sharp distinction that Yerushalmi drew between history and memory prompted an entire generation of scholars to re-examine this relationship. At the same time, Yerushalmi’s probing meditations on the predicament of the modern historian initiated a new degree of reflexivity in the field of Jewish studies and beyond. “Zakhor” was widely acclaimed by critics in the United States and abroad, with Yerushalmi earning a particularly warm reception in France, where he befriended and was admired by scholars and intellectuals, including Jacques Derrida, Pierre Birnbaum, Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, Maurice Kriegel, and Eric Vigne.

In his final major book, “Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable” (1993), Yerushalmi continued to explore the relationship between history and memory, His provocative rereading of Freud’s “Moses and Monotheism” (1939) challenged criticism of that book as a renunciation of Judaism. Yerushalmi recast Freud not only as a student of, but also as a living link in, the chain of transmission of Jewish memory. The book served as a particular source of inspiration to Derrida, whose own work “Archive Fever” (1996) deeply engaged Yerushalmi’s “Freud.” Although the two were friends, Yerushalmi ultimately came to believe that Derrida was not sufficiently attentive to the historical context he drew or to the vocation of the historian.

Yerushalmi’s reclamation of Freud manifested his own deep identification with his subject, who, like Isaac Cardoso and the modern historian of “Zakhor,” struggled to make sense of the Jewish condition in the modern age. Yerushalmi’s decades-long quest to understand this condition, especially poignant in the wake of the Shoah, was an extraordinary contribution to Jewish studies, as well as to the world of letters.

In addition to his brilliance as a scholar, Yerushalmi was an orator and raconteur of rare talent. With a distinctive accent that was part Bronx and part Oxford, he knew how to hold his audiences rapt, whether in large lecture halls or the privacy of his study. But his proudest scholarly legacy was the long series of doctoral students whom he produced at Harvard and Columbia. Yerushalmi was a devoted and demanding teacher, famously intimidating but also compassionate and caring. Those whom he trained have gone on to positions of prominence in universities throughout North America, as well as in Europe and Israel. In the days after his death, many of his students declared that they felt themselves orphans, bereft of the person who had elevated the study of Jewish history to a level of sophistication and artistry barely conceivable before.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi is survived by his wife, Ophra, a concert pianist, and a son, Ariel, and his family.

David N. Myers, a professor of Jewish history at UCLA, studied with Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi at Columbia University from 1985 to 1991.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO