Candidates and Muslim Groups Keep Distance From Each Other

The annual meeting of one of the country’s leading Muslim American organizations is still several weeks away, but the list of probable no-shows currently includes a half-dozen presidential front-runners.

The meeting, to be held December 15 in Los Angeles by the Muslim Public Affairs Council, falls little more than two weeks before the candidates will face their first test of the primary season in Iowa. But as the presidential hopefuls enter the next phase of the race to win endorsements and voters, their likely absence from the MPAC stage reflects a larger lack of engagement with the organized Muslim American community, according to a half-dozen insiders and experts. At the same time, Muslim leaders say, it remains unclear whether they will come together to make a collective endorsement in the race, as they did for George Bush in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004.

Both sides — the candidates and the Muslim community leaders — have reasons for holding each other at arm’s length. The candidates may be wary of getting too cozy with Muslim leaders, including several of MPAC’s top officials, some of whom have been fiercely criticized in the past for making statements viewed as anti-Israel or antisemitic.

Many in the Muslim American community, meanwhile, are wary of jumping head first into the presidential contest, having been sorely disappointed by the policies of George Bush, whom they backed overwhelmingly in 2000.

“Muslims, I think, in the year 2007 are far more sophisticated than they were, say, five years ago,” said Muneer Fareed, secretary general of the Islamic Society of North America. “This is perhaps the second phase in the American Muslim learning experience: You have to support your particular candidate or cause, knowing, however, that you rarely get exactly what you want.”

According to a national survey released by the Pew Research Center last spring, there are 2.35 million Muslims living in America today, following a major influx of Muslim immigrants that began in the 1970s. The current American Muslim population is roughly 65% foreign born, including 24% from Arab countries and 18% from South Asia, while 35% is American born, according to the Pew survey.

The past decade has seen stark shifts in the partisan allegiances of the community, which tends to be in step with the Republicans’ social conservativism but is deeply critical of the Iraq War, the GOP’s anti-terrorism measures and broader policies in the Middle East. While nearly 80% of American Muslims voted for George Bush in 2000 — a result attributable, at least in part, to the Bush campaign’s outreach to Muslim leaders — more than two-thirds backed John Kerry in 2004. According to the Pew poll, more than 60% of Muslim Americans now say they are Democrats or “leaning” toward the Democratic Party. Of the rest, roughly one-quarter are independents or have no party preference, while slightly more than 10% say they are Republicans or lean toward the GOP.

Despite this marked political swing, there have been signs in recent months that politicians in both parties may be seeking to minimize their political risks by distancing themselves from parts of the Muslim American community, as well as from the Arab American community.

In September, the GOP declined to send a representative to a conference held by the Islamic Society of North America, which was attended by the Democratic National Committee’s Howard Dean. Similarly, in October, at a summit held by the Arab American Institute in Dearborn, Mich., the only major candidate to show up was former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson. Several other Democrats sent videotaped messages.

The campaigns of several major presidential candidates from both parties did not respond to the Forward’s request for comment. A spokesman for Mitt Romney said that although the former governor would be unable to attend the upcoming MPAC event due to a scheduling conflict, he planned to send a videotaped message.

Beyond the public forums, several Muslim American observers said there have been unofficial, off-the-record contacts between Muslim leaders and individual candidates and that a number of Muslim Americans are individually active in various campaigns. So far, the only official meeting has been between Senator Barack Obama and ISNA, according to leaders at the organization.

Several Muslim leaders expressed particular frustration with Hillary Clinton, who was lauded by the community for making history as the first First Lady to officially address a Muslim organization, even as she drew widespread condemnation from Jewish leaders for her controversial embrace of Suha Arafat, wife of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, during a visit to Israel in 1999.

Clinton’s reputation in the Muslim community began to sour in the midst of her 2000 Senate campaign, during which she returned $50,000 from members of the American Muslim Alliance after the donations became public. Acknowledging that her office had sent a fundraising letter to the AMA, thanking the organization for a plaque it awarded her at the Massachusetts reception where the money was raised, Clinton nonetheless claimed that she had not been aware that the alliance, some of whose members have been quoted as defending the use of violence against Israel, had been a sponsor of the event.

Clinton “has one preoccupation only, and that is New York and the Jewish vote, [and] any other agenda, even her health care plan, is subsidiary to that,” said MPAC senior adviser Maher Hathout, who is no stranger to controversy when it comes to questions relating to the Middle East.

In 2001, at an MPAC symposium on Jerusalem held at California State University at Fullerton, he reportedly said, “It is obvious at least from our perspective that the United States is also under Israeli occupation.”

According to Farid Senzai, research director at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, it remains to be seen whether a coalition of major Muslim American organizations will make a joint endorsement in 2008, as was the case in both 2000 and 2004, or if the community will eventually move away from the bloc-voting model. While Jews, for example, vote overwhelmingly Democratic, the community generally confines its political endorsements to specifically partisan groups, and tends instead to promote key issues of concern to politicians on both sides of the aisle.

“Muslims see the Jewish community as really having done well in terms of political engagement and political involvement, and as an example that Muslims should replicate and follow,” Senzai said. “But then there have been others that have voiced opposition to that and said, ‘No, we should create our own model.’”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

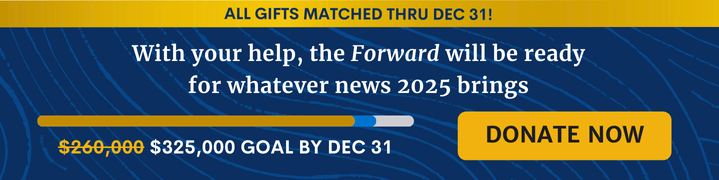

We’ve set a goal to raise $325,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO