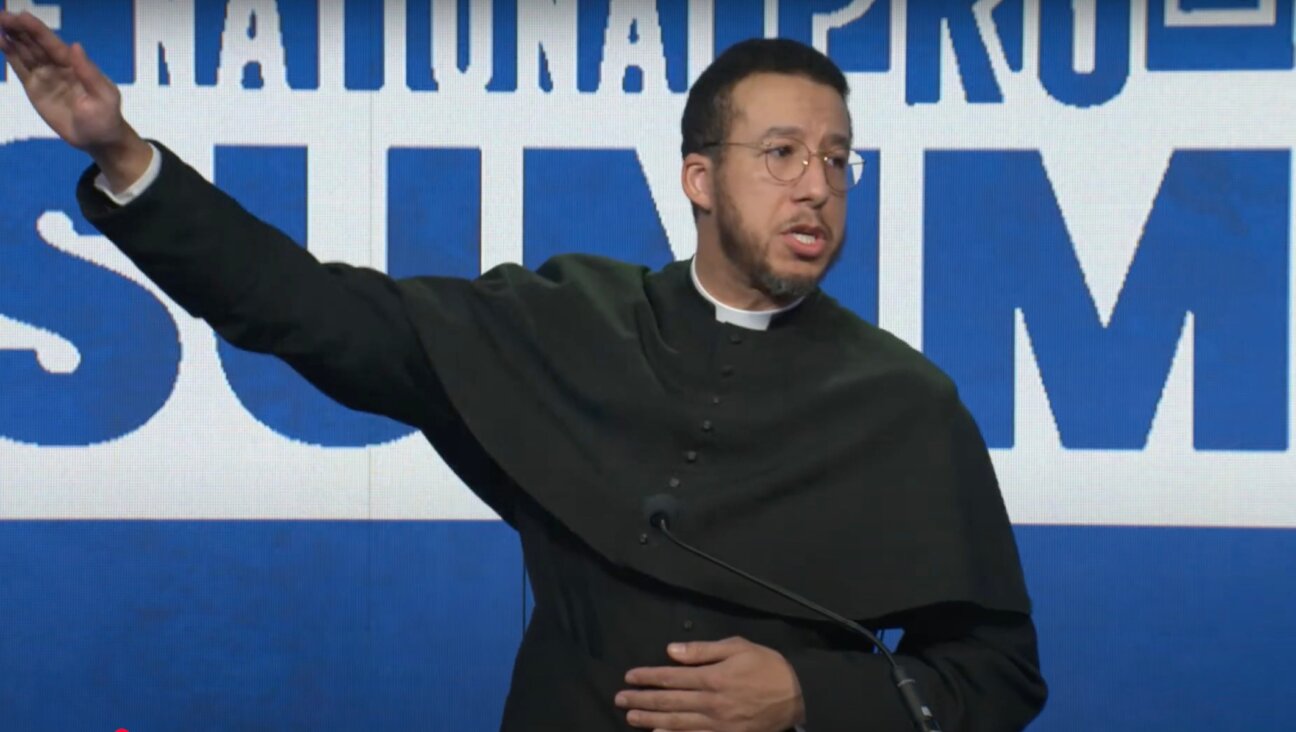

Harvard’s Muslim Chaplain Embroiled in Death-for-Apostasy Controversy

Remarks on apostasy and capital punishment under Islamic law by Harvard’s Muslim chaplain have become the center of a heated debate about whether Islamic and Western values can be compatible.

In an e-mail to an unnamed student, the chaplain, Taha Abdul-Basser, stated that most traditional authorities on Islamic law agree that in countries under Muslim governance, the proper punishment for apostasy — that is, rejection of Islam by a former Muslim — is death. The e-mail was subsequently published online, and although Abdul-Basser has distanced himself personally from that position, the remarks have stirred a flurry of controversy and debate.

Abdul-Basser’s e-mail was circulated through an e-mail list and subsequently posted April 3 on the blog Talk Islam, from which it was picked up by several other blogs. On April 14, The Harvard Crimson, a student-run daily, published an article about the controversy. One week later, on April 21, it remained the paper’s most viewed, most commented-upon article online.

The issue being debated is anything but academic: Apostasy is outlawed in a number of Muslim countries, including Afghanistan, Malaysia, Iran and Algeria. In 2006, an Afghan named Abdul Rahman faced trial, with a potential sentence of death, for converting to Christianity, before being granted asylum in Italy. The issue has attracted a great deal of attention from such international human rights groups as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

In his original e-mail, Abdul-Basser appeared to put himself at odds with the international human rights community, which includes a number of luminaries who teach at Harvard. After a lengthy discussion of the positions of various Muslim autorities, he concluded by writing that “there is great wisdom (hikma) associated with the established and preserved position (capital punishment), and so, even if it makes some uncomfortable in the face of the hegemonic modern human rights discourse, one should not dismiss it out of hand.”

In a subsequent statement sent to the Forward, however, Abdul-Basser said that he was simply explaining to a student the traditional position of Islamic legal scholars, not advocating their viewpoint.

“I have never expressed the position that individuals who leave Islam or convert from Islam to another religion must be killed. I do not hold this opinion personally,” Abdul-Basser wrote, adding that the “wisdom” he referred to simply described the skill of the scholars who have historically debated the laws on apostasy.

“I was not advocating any of the positions summarized in my e-mail, merely addressing them in the context of the evolution of an Islamic legal doctrine,” he added.

Abdul-Basser’s original e-mail did also note that a number of Islamic thinkers have contested the notion that apostasy ought necessarily to be punished by death under Muslim law. But this has not satisfied some of Abdul-Basser’s critics. On the Web site Beliefnet, Muslim blogger Aziz Poonawalla took issue with Abdul-Basser’s contrast between Islamic law and human rights.

“The phrase, ‘hegemonic human rights discourse’ is deeply troubling because it implicitly rejects the basic notion of universal human rights,” Poonawalla wrote. “Freedom of faith and conscience is a key human right that has solid precedent and grounding in Islamic sources as well as Western roots. I reject the notion that human rights are ‘values’ which may be fluid between human societies. It’s precisely this attitude that has permitted modern Islamic states to drift so far from the established jurisprudence.”

Other critics have taken a still harsher line, calling for Abdul-Basser’s dismissal.

“This case is typical of many others; Muslim leaders, portrayed as moderate and occupying prestigious and responsible positions, turn out, in fact, to be Islamists,” said Daniel Pipes, who founded Campus Watch, an organization dedicated to rooting out and criticizing university professors and student groups that it considers to be excessively Islamist or antisemitic. “Only when institutions like Harvard engage in proper due diligence to exclude Islamists can we begin to fight the enemy within.”

Abdul-Basser’s position, however, is by no means unusual, according to Bernard Haykel, a scholar of Islamic law and history at Princeton University. Haykel said that Abdul-Basser’s statement is an accurate description of a well-established branch of traditional Muslim law.

“It’s a fairly difficult law to overcome, because the sources on which it’s based — the penalty of death for apostasy — are pretty sound sources, they’re pretty difficult to refute,” Haykel said. “To refute them requires a break, a rupture with tradition.”

Haykel also noted that Abdul-Basser’s position — that such a penalty is justified only under the auspices of a Muslim government, following the due process of Muslim law — is far more limited than what is advocated by a number of radical Islamists: “I think that what he’s reacting to is that a number of Islamist groups, including Al Qaeda, have said that you can forget the whole context of an Islamic state. In fact, you can sort of privatize this form of ruling. You don’t need a state, you don’t need proper courts, you don’t need due process. You can take the law into your own hands and kill apostates.”

Haykel said that in practice, in non-Muslim countries, those who view apostasy as a serious offense typically shun those who leave Islam. “My sense is that Muslims have dealt with these cases the way Jews have, or Christians; they’ve probably ostracized them and kicked them out of the community,” he said. “It’s the story of ‘The Chosen’ all over again.”

Contact Anthony Weiss at [email protected].

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO