‘I feel I must be vocal:’ a budding activist talks racism in Jewish spaces

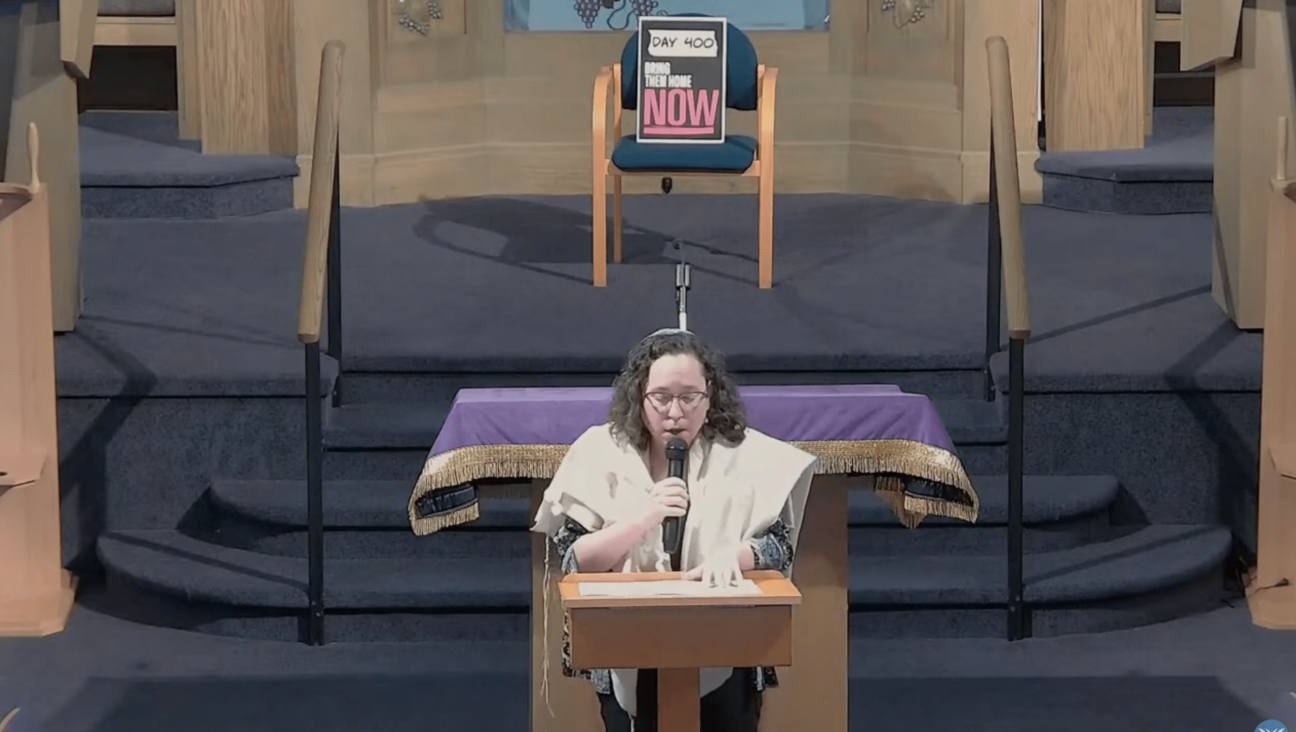

Jessica Schachter with her two children at a protest against police violence in Montclair, N.J. Image by Courtesy of Jessica Carter

A light rain was falling by the time the convoy of cars arrived at Nishuane Park in Montclair, N.J., where a stone memorial commemorates the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. But the masked demonstrators who emerged to lay bouquets and notes near the plinth were reluctant to disperse. The mobile protest had gathered hundreds of residents in a socially distanced demonstration of solidarity with the black community, and no one seemed to want it to end.

Jessica Schachter, a retired attorney and longtime Montclair resident who describes herself as both black and “proudly Jewish,” was especially proud of the turnout. While not formally affiliated with the Montclair Education Association, which organized the demonstration, she made it her mission to get people in their cars and on the road. “I posted on social media, I printed flyers, I texted and sent emails, I told neighbors,” she said.

Until the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers in May, Schachter didn’t consider herself particularly outspoken about racism that she’d experienced or witnessed. Now, she says she can talk of little else.

“My kids are wondering what’s wrong with me,” she said, joking about the sharp uptick in her social media activity in recent weeks, “but I feel I must be vocal. I feel very strongly now that if you’re not for us, you’re against us.”

Like many Americans, Schachter is evaluating her own role in a deepening national conversation about racism — a conversation that, in her own family, began before she was even born.

When Schachter’s father, an Orthodox Jew raised in New York City, announced his intention to marry a black woman who had converted to Judaism, his parents stopped speaking to him, sitting shiva as if he had died. As young parents, the couple moved from crowded Brooklyn to suburban Montclair. It was a sensible choice for a growing interracial family: the town boasted a thriving black middle class and had recently integrated its public schools through a busing campaign.

Montclair didn’t always live up to its reputation for integration. Schachter said she’d been racially profiled by police and followed in stores. But, she said, her worst experiences with racism came where she most hoped she would feel welcome: within the Jewish world.

At synagogue, it didn’t matter that Shabbat dinners were non-negotiable in her family, or that she recited a shehecheyanu blessing each Friday in honor of the “ancestors who couldn’t always do that openly and freely.” Instead, Schachter often noticed people looking at her with suspicion.

“I’ve been asked by Jews if I’m really Jewish, how I celebrate, if I can say something in Hebrew,” she said. “It’s exhausting to be questioned all the time when you just want to pray.”

Schachter, who is raising her two children Jewish, said the skepticism never shook her confidence in her own identity. “It has disappointed me for sure, and it has made me walk out of synagogues. But it’s never made me question who I am,” she said.

That’s not the case for everyone in her family. As an adult, one of Schachter’s sisters converted to Catholicism, the religion with which their mother grew up. “Nobody questions her when she says she’s a Christian,” Schachter said.

Asked how synagogues should change, Schachter said that gestures of inclusivity won’t bear real fruit until white Jews fundamentally challenge the assumption that all members of the tribe look like them. She’s had some of her best Jewish experiences at her current synagogue, Temple Shalom in West Essex, N.J., where the rabbi’s two adopted children are black.

“I’ve never seen him speak to anyone about Jews of color but there’s a [welcoming] environment that he’s clearly created,” she said.

MHS students organized The Black Lives Matter Unity march on Sunday, June 7; more than 4,000 people participated. https://t.co/LKOcI9gJmV pic.twitter.com/qurlHXUhbj

— Montclair Local Nonprofit News (@montclairlocal) June 10, 2020

Looking for a way to take concrete action, Schachter has turned her attention to Montclair’s public schools. Despite a reputation for rigor and diversity, a significant achievement gap persists between black and white students in the district. And a recent protest organized by high school students left Schachter aghast at the casual racism black teens said they experience: at the event, one group of black girls recalled white boys telling them to “go get our food stamps.” Another student was instructed by a math teacher to “not talk like a slave.”

Schachter has marshalled a group of friends to meet with student organizers and leaders of the school’s restorative justice program, and is encouraging even those without school-age children to make their dissatisfaction known. She hopes to create a survey to collect hard data on how and when public school students experience racism.

“We want to let them know there are some pretty tough mamas in this town who have their back,” she said. “That we want to help them.”

Irene Katz Connelly is an editorial fellow at the Forward. You can contact her at [email protected].

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO