Teaching In Qatar — And Keeping My Jewish Identity Secret

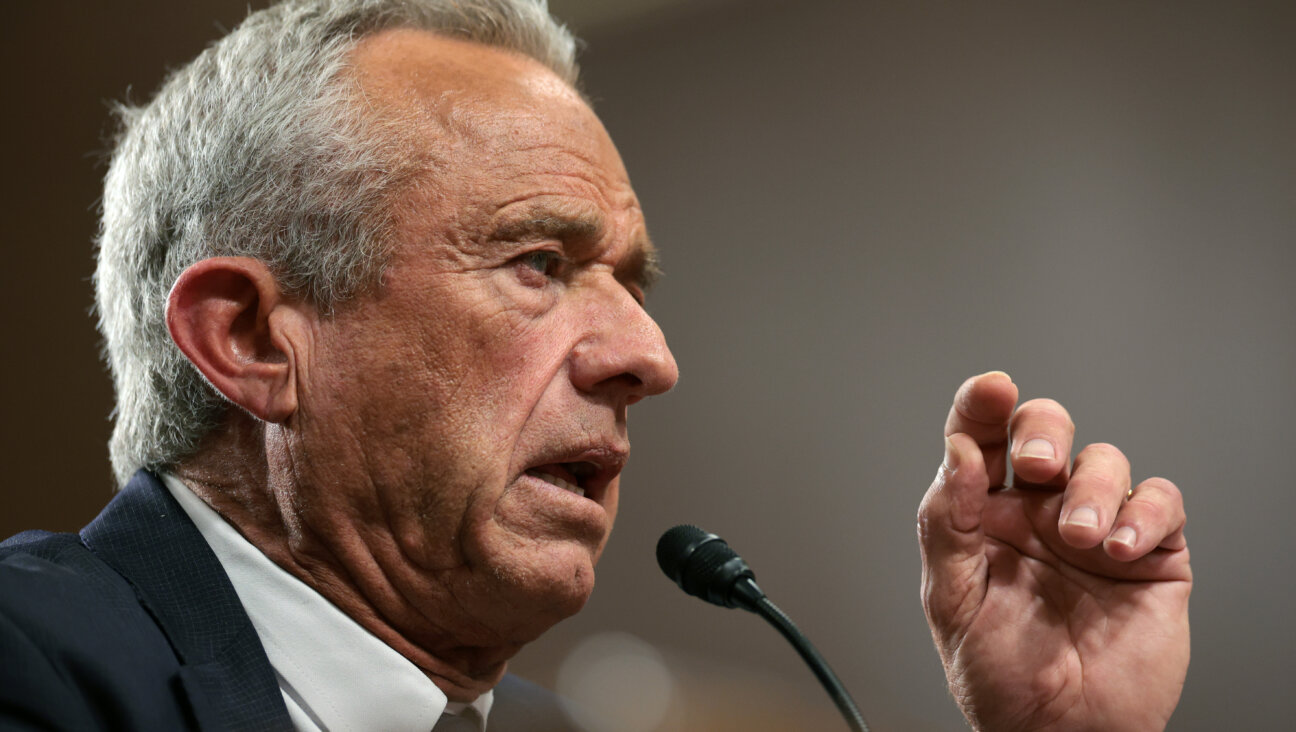

Image by Getty Images

“I have my religion, and you have your religion.’ Qur’an (109:6)

One of my best students, Assad, came up to me one day after Introduction to International Relations class to ask, with a smile, if he could touch me.

Turning to his friend with a twinkle in his eyes, he grinned that he had never touched a Jew before. It was a reminder that very few of my Arab students knew any Jews.

With a shrug, I obliged.

Later he would tell me what little he had learned on this racy topic in his exclusive private school in Saudi Arabia. Beyond insights that Al Gore was a Jew, there was his Islamic studies teacher’s certainty that Israel’s Mossad was behind 9/11. This was followed by the curious bias—heard elsewhere in the region— that Arabs were incapable of planning such a complex, successful operation, and that the US had it coming anyway.

I asked how his teacher could both support the attack on 9/11, yet see it as some mammoth Zionist conspiracy, presumably serving Israeli interests. He looked at me for a moment, resigned that yet another naïve foreigner could not appreciate how holding two contradictory conclusions at the same time was utterly consistent with local logic.

My conversation with Assad took place a couple years into teaching at the newly established branch of the Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Doha, Qatar.

When I first arrived, I was advised to keep my faith to myself.

Another political scientist in Washington who was an expert on the region -— which I was not — described becoming “a private Jew” when he lived in various Arab countries. This meant not revealing your religion and avoiding public debates on contentious topics, like Israel. His advice was that it was easier not to broadcast your religion, though you might quietly share this with friends and a few close associates. The parallel dilemma facing gays in these conservative societies came to mind: gay friends in Qatar generally kept their homosexuality quiet and discreet.

I added to this my own reasons (or perhaps excuses?) for keeping my Judaism to myself. One was that I didn’t want to be ‘the Jewish professor’ (for most of my time in Doha, I was Georgetown’s only one). That wasn’t what I was doing, wasn’t how I saw myself, and wasn’t how I wanted to be identified. I was concerned that the ‘Jewish’ label would dominate me. I didn’t want the burden of representing the other 16 million Jews in the world that my students hadn’t met. I was a professor of American politics, and that was all.

*

The option of being ‘a private Jew’ was, as they say, overtaken by events. If I wasn’t going to deny my heritage, I would have to accept it.

Early on, students googled my last name to see if there were other Wassermans who could be readily identified as Jews. The conclusions, I was told, were mixed. One Student Affairs staffer declared me to be Jewish. I took umbrage at this—it was none of his business. He replied that he thought it was general knowledge. I asked him if he identified other faculty members by their religions. He frowned.

My secret identity couldn’t stay concealed for long. Doha is a small place. During my multiple interviews when I was applying for my position, one American dean asked me if I was Jewish. After a solemn nod, he noted that, ‘Well we had to hire some of you guys sooner or later.’ At the time, I consoled myself in the thought that — should nothing else work out — his very illegal question could produce a successful lawsuit paying almost as much as the job, and without the aggravation of moving to a fundamentalist Arab emirate.

There was no one moment when I ‘came out’. Americans on the faculty mostly assumed my ethnicity; others might have but were too polite to inquire. Some might ask where I was from and, when I said I had been born in Washington, DC, they said they thought I was from New York. (Like most Jews?)

As I emerged in my public identity, I made two discoveries in Gulf Arab attitudes toward Jews.

One was that very few of my students knew any Jews. They couldn’t identify Jewish names or begin to distinguish who was or was not Jewish in the expat community. I never saw any racial typecasting — dark skin, black beards, prominent noses — which of course would have included a large number of Arabs. Jews were accepted, at least in theory, as members of the same ancient Abrahamic faith as Moslems making us, along with Christians, People of the Book. This gave members of these faiths a leg up on Hindus and Buddhists, whose appreciation for multifaceted dieties put them considerably lower on the Moslem food chain of acceptable religions.

Jews were both adversaries of The Prophet and precursors of his mission. Present-day Israelis were clearly the Zionist enemy, the last Western colonizers cruelly occupying Arab lands. But Jews from Europe and America fell between the poles, and since they were seldom encountered in the Gulf states, they remained an ambivalent mystery. The lack of observable data didn’t inhibit the rhetoric. Bigoted local mullahs would be quoted in the local press referring to ‘vermin’ when sermonizing about The Tribe.

But my students surprised me in the other direction — by elevating Jews to extraordinary levels of intelligence and power. To half believe the conspiracy theories embodied in that Czarist fable, Protocols of The Elders of Zion (available in Doha bookstores) is to credit a tiny minority for the behavior of the global economy — mostly depressions, power politics, and world wars. If this small group is guilty of so many world-changing events, clearly one must be dealing with impressive individuals.

An Egyptian student recalls my telling a joke that spoke to this inflated notion of Jewish omnipotence: An iconic anti-Semite goes down a list of tragedies caused by Jews, including the sinking of the Titanic. He’s corrected that the Titanic was sunk by an iceberg. “Iceberg, Rosenberg, Steinberg, what difference does it make which one did it.” My student recalls hesitating in her response, not knowing whether it was appropriate to laugh.

The joke did reflect a curious attitude I found in my students. In deference to my origins, many assumed that whatever I said about the workings of Washington had the added luster of an inside-dopester. Arguably, being Jewish gave me access to the inner-circles of the American elite. Presumably, I was sharing insights garnered from power-brokers that I had learned during weekly services at the local synagogue. I modestly demurred.

But my attempts to humble myself down to a more realistic just-another-professor-reading-The New York Times was, I confess, half-hearted. After all, as my students understood, such conspiracies needed to be kept secret.

*

After eight years of teaching in Doha, I retired.

Whether my teaching made any difference to our school or to the students, I am not sure. I knew what I was teaching, but I was never certain what my students were learning. There were, however, moments that seemed to justify the time.

Mohamed was a student in my Introduction to International Relations class. Bright and attentive, he wore the robes of a young Qatari man and spoke up frequently in class. Alas, whatever the topic being discussed, his comments often seemed to relate the subject back to Zionism, Israel or Jews. Issues of international law would merit a reference to the invasion of Gaza; the causes of World War I might merit a question about the Zionist movement; the boycott of Cuba somehow was tied to the pro-Israel lobby in Washington.

When a student tried to steer the discussion in directions that were consistently off-point, I generally let the class herd the questioner back on topic by opening the question to them. After a while, the class provided that service. Mohamed didn’t completely give up his commentary parading as questions, and at some point, I spoke with him in my office. While I said I was willing to give him the benefit of the doubt, I told him his comments diverted the class and wondered whether his questions were aimed specifically at me. I am sure I communicated more annoyance that I had planned. He denied any but scholarly motives. I concluded our meeting by suggesting that at some point he take a class that might answer more of his questions. At the time, I didn’t consider our chat terribly productive.

Mohamed was a good student and he did well in the class.

I didn’t see him for about a year afterward. And then on a spring day, he knocked on the door of my office and asked to come in. He said he had spent the previous semester of his junior year at Georgetown’s Washington campus, where he had taken a class on the history of Jewish civilization. He said he liked the class a lot and added, ‘I never would have taken that class if I hadn’t been in your course.’

Go know.

Gary Wasserman was a professor of politics at Georgetown University and the author of The Basics of American Politics (15th ed.) and [The Doha Experiment: Arab Kingdom, Catholic College, Jewish Teacher (forthcoming)] (https://www.amazon.com/Doha-Experiment-Kingdom-Catholic-College/dp/151072172X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1509470123&sr=8-1&keywords=9781510721722).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO