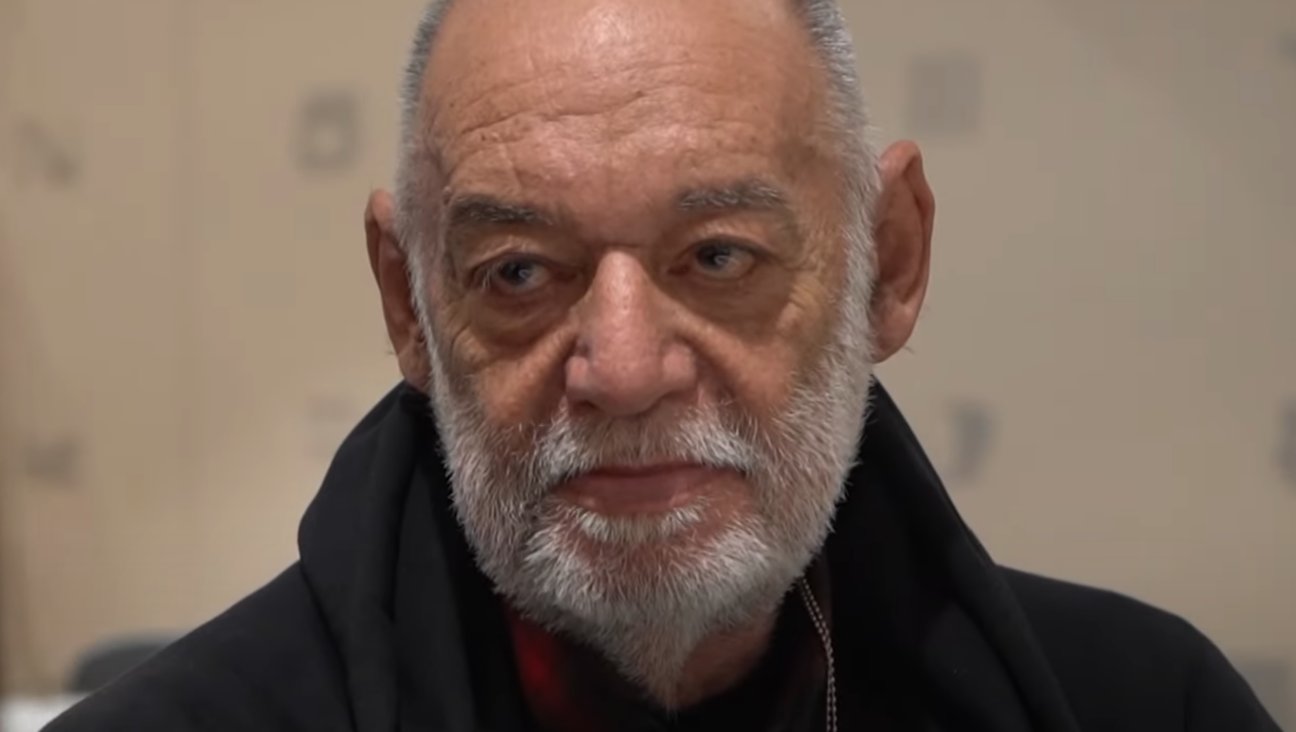

Q&A With ‘Paternity Test’ Author Michael Lowenthal

Michael Lowenthal’s fourth novel, “The Paternity Test,” is a beautifully told story that brings myriad social issues to the forefront, and also manages to be a literary page-turner.

Lowenthal’s work is hard to categorize. His first book, “The Same Embrace,” told the story of identical twins, one of whom became gay while the other became an Orthodox Jew. “Avoidance” explored the cloistered worlds of the Amish and the protagonist’s long-ago summer boys’ camp. “Charity Girl” took up a little-known chapter of American history when women were incarcerated during the First World War in a government effort to contain venereal disease.

Versatility is a hallmark of Lowenthal’s work, as is the 43-year-old writer’s gift for language and depth of character. “The Paternity Test” gracefully merges gay marriage, Jewish identity, sexuality, the Holocaust, Jewish continuity and sexual fidelity in one story.

Pat Faunce and Stu Nadler have been together for a decade. Pat is a blue blood (there’s a small street named after his family near Plymouth Rock) and a failed poet who earns his living by writing textbooks. Stu, a dashing airline pilot, is the son of a Holocaust survivor who, as Lowenthal recently described him in a conversation over coffee, “has a boy in every port. But their ‘no rules relationship’ is starting to wear on them. So in a 21st century twist on saving their ‘marriage,’ they decide to have a baby.”

The issue of Jewish continuity following the Holocaust further complicates the story. Stu’s sister, Rina, recently married Richard, a nice Jewish boy, but she cannot conceive. Meanwhile, Stu also feels the pressure of passing on the Nadler genes.

Lowenthal’s grandparents escaped the Holocaust just before deportations began in Germany. The grandson of a rabbi, he has a multi-pronged answer when asked if he considers himself a Jewish writer:

I was raised in a [Conservative] Jewish household, and three of my four novels prominently feature Jewish characters and Judaism-related plot elements, so yes, obviously, I’m a Jewish writer. I’m reminded of a remark by a gay writer when he was asked if there is such a thing as a gay sensibility, and, if so, what effect it has on the arts. He said, ‘No, there is no such thing as a gay sensibility, and yes, it has an immense impact on the arts.’ Maybe the same thing could be said of Jewish sensibility?

Stu and Pat’s search for a surrogate begins, as does an intense exploration of Jewish identity. After visiting various agencies and trolling surrogate sites on the Internet, they settle on Debora Cardozo Neuman. In Stu Nadler’s surprisingly traditional mindset, Jewish babies must be born to Jewish mothers and Debora fits the bill, albeit in an unusual way. A native of Brazil, she comes from a converso background — generations before her, Jews practiced Catholicism outwardly yet clung to their Judaism. Now Deborah follows a set of quirky habits and mysterious dietary restrictions until the community uncovers its Jewish roots.

While Stu is taken with Debora’s story, Lowenthal raises the stakes: Rina and Richard adopt, which causes Richard to lose himself in the “minutiae of Judaism. Richard pays attention to legalistic questions that shouldn’t trump choosing to raise a child in a Jewish home. For him it’s not enough. It’s better if the child is converted shortly after birth to avoid the possibility of having a mamzer.”

A mamzer is a child considered to be illegitimate if born to a woman who has conceived a child outside of her marriage. Like the plight of the aguna — a woman who is legally stranded in a marriage because a husband refuses to grant her a Jewish divorce or a get — mamzerim have no control over their fate or their standing in the community. While liberal branches of Judaism have done away with the mamzer status, Richard adheres to ultra-Orthodox tradition and in the process destroys his marriage.

Place is also important to Lowenthal. Pat and Stu relocate to a house on Cape Cod very similar to the one in which Lowenthal spent his summers. His Portuguese sounds flawless to this Spanish speaker’s ear as I ask him about the word saudade — a word that Debora uses when describing Pat and Stu’s need for a child.

“Saudade describes a deep longing for something that can never be recaptured,” he explained. “It’s about the immigrant who can’t return to his homeland because so much has changed. It’s the fantasy of family — the mythical idea of who they are.”

There’s no question that a feeling of saudade permeates “The Paternity Test.” Each character has his or her own saudade in longing for a baby. And their complex desires irrevocably change life for Stu, Pat and Debora in ways they could never imagine.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO