Communal Pressures To Get a Get

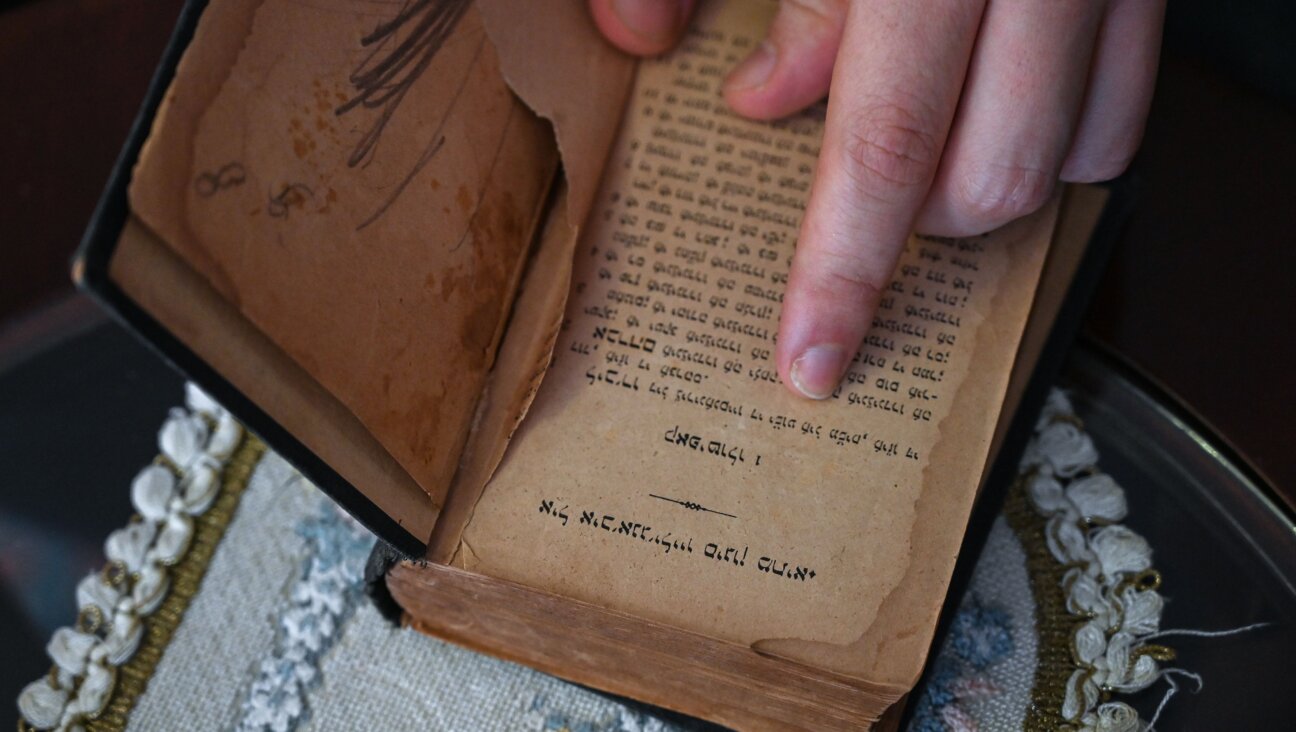

I come from a family where halacha is championed alongside the freedom and power of the individual. It is a hard balance to forge, and it is one that comes with contradictions and hurdles. Recently in the news was the story of a Capitol Hill staffer who would not grant his wife a get, or a Jewish divorce decree. On the one hand, I find there to be something sacred about the untouchable nature of halacha. On the other hand, I cannot support a belief system that allows for women’s freedoms to be taken away without any real repercussions according to the law.

I emailed a New York Times article about the divorce dispute to a friend, who subsequently expressed his dismay that the Orthodox belief system could survive with such an edict intact. I argued that at least the Orthodox community is taking measures against those men who refuse their wife a get. At present, a common communal response against a man who leaves his wife an agunah, or a chained woman, is social pressure and threats of being ostracized, in addition to other halachic creations like prenuptial agreements and inserting minor mistakes in the wedding ceremony that could allow grounds for a halachic divorce without needing a get.

My friend countered my explanation with a jolting comparison — to rape. He argued: If a society did not have a law against rape, just a general disapproval, and the only course of action against rape was social bullying, would that be the most rational solution to the problem of sexual assault? I was shocked by the comparison, but mostly because of the relevancy: I do not equate rape with the refusal to give a woman a get; however, I do see how women who are not given Jewish divorces essentially have their sexual and emotional freedom taken away from them.

Dorothy Lipovenko, [writing recently on the Sisterhood blog asked the questions: “Is the will there to reform the get laws? And if it’s lacking, is it for the wrong reasons?”

In Judaism, according to my personal interpretation and practice, halacha and community are inextricably linked. Halacha sets up the boundaries for the community, but the community attracts people to halacha. Where halacha lies powerless to change, the community must use its own power and appeal to make up for the impotence of the law.

According to Jewish marital standards, halacha demands social ostracization: We all know the famous scene in “Fiddler on the Roof,” in which Tevye banishes his daughter for marrying a non-Jew. However, this issue of intermarriage is no longer so black and white today. Different Jewish communities address it with varying responses. Similarly, various Jewish communities have decided to address the get issue in their own ways, for example, by issuing a statement against agunot in pre-nuptial agreements. In these cases, the halacha itself responds to the community.

However, my friend is right: Social bullying is not the correct response to the law’s shortcoming. But he clearly picked up on a trend of power within Judaism: that of the community. We should leverage that power to challenge halacha. Community and halacha are, after all, equal partners.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO