She chronicled life’s magic moments — the milestones and the mundane

Sally Friedman, a New Jersey columnist and the mother of my close friends died at 86 after years of debilitating dementia

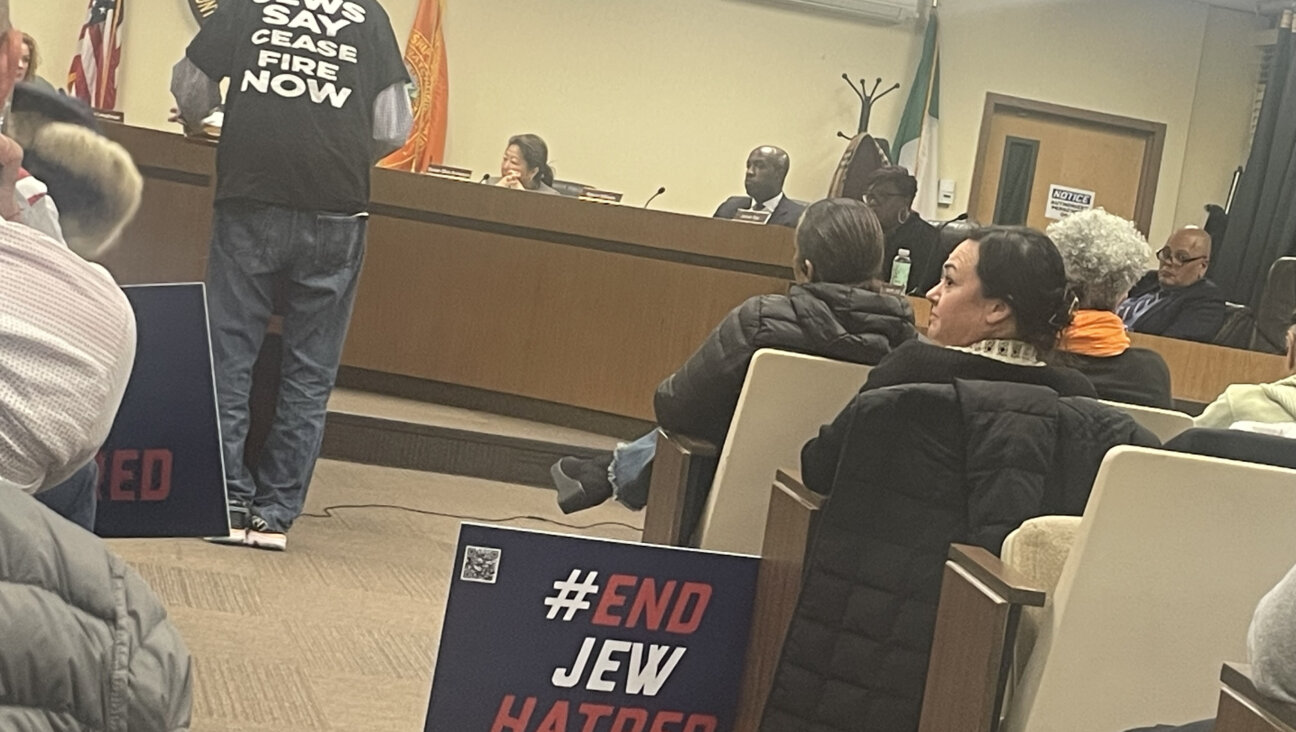

Sally Friedman, an accomplished Jewish journalist who wrote about everything from motherhood to Fiddler on the Roof passed away last week. Photo by Adam Monacelli / Burlington County Times

This is an adaptation of our editor-in-chief’s weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox on Friday afternoons.

Sally Friedman knew the exact moment that sparked her half-century career chronicling life’s milestones and magical little moments. It was March 30, 1964, “long before home births were in vogue,” as Friedman later wrote in an essay, when she accidentally gave birth in her suburban bedroom to the second of her three daughters, and her lawyer-husband “became an instant obstetrician.”

A few days later, she scratched out the story on said husband’s yellow legal pad. A few weeks later, she sent the handwritten pages off to what she later described as “a very prestigious publication — the magazine that came with our diaper service.”

That magazine was Baby Talk, and offered Friedman $12.50 for the piece, payable in cash or diapers. She took the diapers.

Friedman was 86 when she died last Friday morning after several years of debilitating dementia. She is survived by her husband, Victor, a retired New Jersey Superior Court judge; a sister, Ruthie Rovner, who is also a writer; those three daughters, who are close friends of mine; seven delightful and impressive grandchildren; and thousands of insightful, moving, witty essays, mostly in South Jersey newspapers, about — well, about everything that really matters.

Here’s Sal, as people called her, on marriage (hers with Vic lasted 64 years):

“Togetherness has taught me that a steamy bathroom mirror is better, alas, than none; that closing closet doors is a moral imperative; that morning people (him) and night people (me) can ultimately learn to coexist in the glow of the afternoon.”

On mothering teenagers: “It means words unsaid, because silence IS sometimes golden even though her haircut looks strangely asymmetrical, and even though the young man she has chosen this time around needs a course with Amy Vanderbilt AND a haircut, and even though you know she’ll be sorry that she chose a passionately purple winter coat with pink piping.”

And on attending the shiva of a friend who lost her mom, as I did with Sal’s daughters this week: “We sit huddled around her like a loving honor guard, trying to pierce the pain of her loss. We ply her with coffee and tiny sweet cakes carried in by neighbors who soundlessly serve and clean up. We are ‘the girls,’ and in time of deep trouble or soaring joy, we come together.”

I first met Sal a few years ago, when I joined Amy — the daughter whose unwitting home birth sparked it all — for a Sunday visit to her parents at their memory-care facility near our homes in Montclair, N.J. Both Sal and Vic were already struggling to recognize Amy and her sisters, Nancy and Jill, never mind keep track of new people. But they were in joyful moods and embraced me as if they’d known me forever.

We spent a while in circular conversation that was at once heartbreaking and hilarious. Then Amy took out a booklet Sal made in 1983 collecting some of her favorite “Lifesounds” columns from the Burlington County Times, in southern Jersey, and read her mother’s poignant words aloud.

“Who wrote that?” Sal asked.

“You did, Mom,” Amy said. “You’re a wonderful writer.”

Sal agreed the column — it was the one about mothering teenagers; specifically, about waiting for Amy to come home one February night during a sleet storm — was pretty good. When Amy finished, she told Sal that I, too, was a writer, and that I had a weekly column in the Forward, just as she had in the local papers for decades. Then Amy handed me the booklet, and I read Sal and Vic the “Dearest Valentine” column she’d written for him decades before.

“If our love is sometimes a graceful waltz under a crystal chandelier, it is more often a fast two-step to the hardware store for light bulbs, and the discount store for ant killer,” I read, simultaneously tearing up and laughing. “If our love is moonlight and roses, it is also sunburn and sand in the bathtub.

“There are women out there who wear lip gloss and size 6 jeans, and you still come home to me. There are men out there who pen poetry and send violets on a whim, and still, I wait for the sound of your footsteps and the lyric quality in your voice as you pose the eternal question: ‘What’s for dinner?’ Love at its most basic is my answer: leftovers.”

When I was done. Sal asked, “Did you write that?”

No, we said. You did.

“Lifesounds” was Sal’s mainstay, a column that ran from 1971 (the first, headlined “The Last First Day,” was about dropping her youngest, my future friend Nancy, off at kindergarten) until she retired in 2022. An English major at the University of Pennsylvania (class of 1960), Sal also did feature stories and restaurant reviews; published essays in The Times and other places, many later collected in the Chicken Soup for the Soul anthologies; and ghost-wrote innumerable speeches — wedding vows, eulogies, award acceptances — for extra cash.

She wrote most of it on a Smith Corona typewriter — the kind with the separate white ribbon to fix mistakes — on the kitchen table in the heart of a huge Moorestown, N.J., home filled with thrift-shop finds (“Mom had an incredible eye,” Amy said).

“We would just move the typewriter when it was time for dinner,” the eldest, Jill, recalled in a video interview for Sal’s retirement. “Her writing was literally at the center of our family life, and our family life was at the center of her writing.”

Jill, who grew up to be a lawyer like Vic and now runs the pro bono and public interest program at Rutgers Law School, did not love this. She particularly did not love when Sal wrote about Jill’s first date, in sixth grade. “We just had a different sense of privacy,” Jill said.

Amy, who went on to create TV for kids at Nickelodeon and Warner Bros., said she took a “no big deal” approach to it all. Like Sal, Amy lives life out loud, and she said she only read “maybe 20%” of her mom’s work anyhow.

Nancy, a psychologist, was also unbothered. “Maybe I’m a bit of an exhibitionist,” she said this week. “The joke was always that everybody was going to know when I got my period for the first time. But she managed to do it in a way that didn’t feel invasive or intrusive.”

Sal, tan and glamorous in old photos, never worked 9 to 5 or in a newsroom. She was always a freelancer, always home to greet the girls after school or drive carpool — and always on deadline. The columns often poured out of her in 20 minutes, late at night. In a pre-internet era, Vic would drive her over to the newspaper’s office to deliver the printed pages.

She wrote about her own first day of kindergaten, about becoming an empty nester, about collecting old cleaning rags. Her first trip to Israel and a trip to the cosmetics counter. What she gave her grandchildren instead of Hanukkah gelt, shopping for her 97-year-old mom’s final sofa and the book group that met religiously for 50 years.

She had tons of devoted readers, who would gush when they ran into her at the supermarket or library, and call the house with a story idea or comment. She answered every piece of fan mail.

“In a feature, she always found the human side,” Amy said, “and in her columns it was that really amazing synergy of specificity and universality.”

“If she was writing about the guy who made the sets for Fiddler on the Roof,” Nancy added, “It wouldn’t be about the set; it would be about the fact that while he was making the sets, his mother was dying of cancer.”

The sisters described Sal’s voice as a mix of Erma Bombeck and Judith Viorst with a touch of Anna Quindlen — all writers she’d admired and devoured.

“Her special sauce was when she was very moving and very funny,” Amy said. “I don’t think mothering was enough for her. This allowed her to be a whole person.”

“We would just move the typewriter when it was time for dinner. Her writing was literally at the center of our family life, and our family life was at the center of her writing.”Jill FriedmanSal's eldest daughter

At Sal’s shiva, the sisters asked our rabbi and cantor to mix John Denver songs into the liturgy — Sal loved John Denver, and long after she lost her words she would respond to his. As we sang together, “Take Me Home, Country Roads” and “Sunshine on my Shoulders” and “Leaving on a Jet Plane” but also the words of the Shema and Mi Chamocha, my own teenage daughter marveled at the power of the voices. “This is what community sounds like,” I whispered through my tears.

Sal’s eldest granddaughter, Hannah, read the column about waiting up in a storm to make sure teenage Amy got home safely.

“I love them fiercely, so fiercely that it ‘knocks me out,’ as they would say,” she’d written all those years ago about exactly how I feel right now. “I have also been known to hear a stranger’s voice screaming at them, violating every principle of perfect motherhood and calm control. I shudder when I recognize that voice as mine.”

Suddenly, in a moment Erma Bombeck would have appreciated, Hannah was interrupted by the ringing of a cell phone. It belonged to 92-year-old Alan Rockoff, who was in the Jewish fraternity Zeta Beta Tau with Vic at Rutgers University in the 1950s. The ring tone was loud and sing-songy, and it announced the caller’s name, “Marty Friedman.”

Rockoff ignored it. But the caller kept calling back, making the crowded room erupt in laughter. Finally Rockoff picked up and barked, “I can’t talk right now; I’m listening to Sally.”

Hannah returned to reading the column: “I know that the tighter I squeeze, the harder they will pull away.”

Vic’s ZBT brother and Sal’s friend of 70 years sweetly asked: “Can you go back one paragraph?”

She did, and we were all happy to hear Sal’s wise words again.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO