An Israeli hip-hop artist remembers a day of hope in Gaza

Shaanan Streett of ‘HaDag Nahash’ spoke to Libby Lenkinski on the Forward’s new podcast ‘Make Art, Not War’

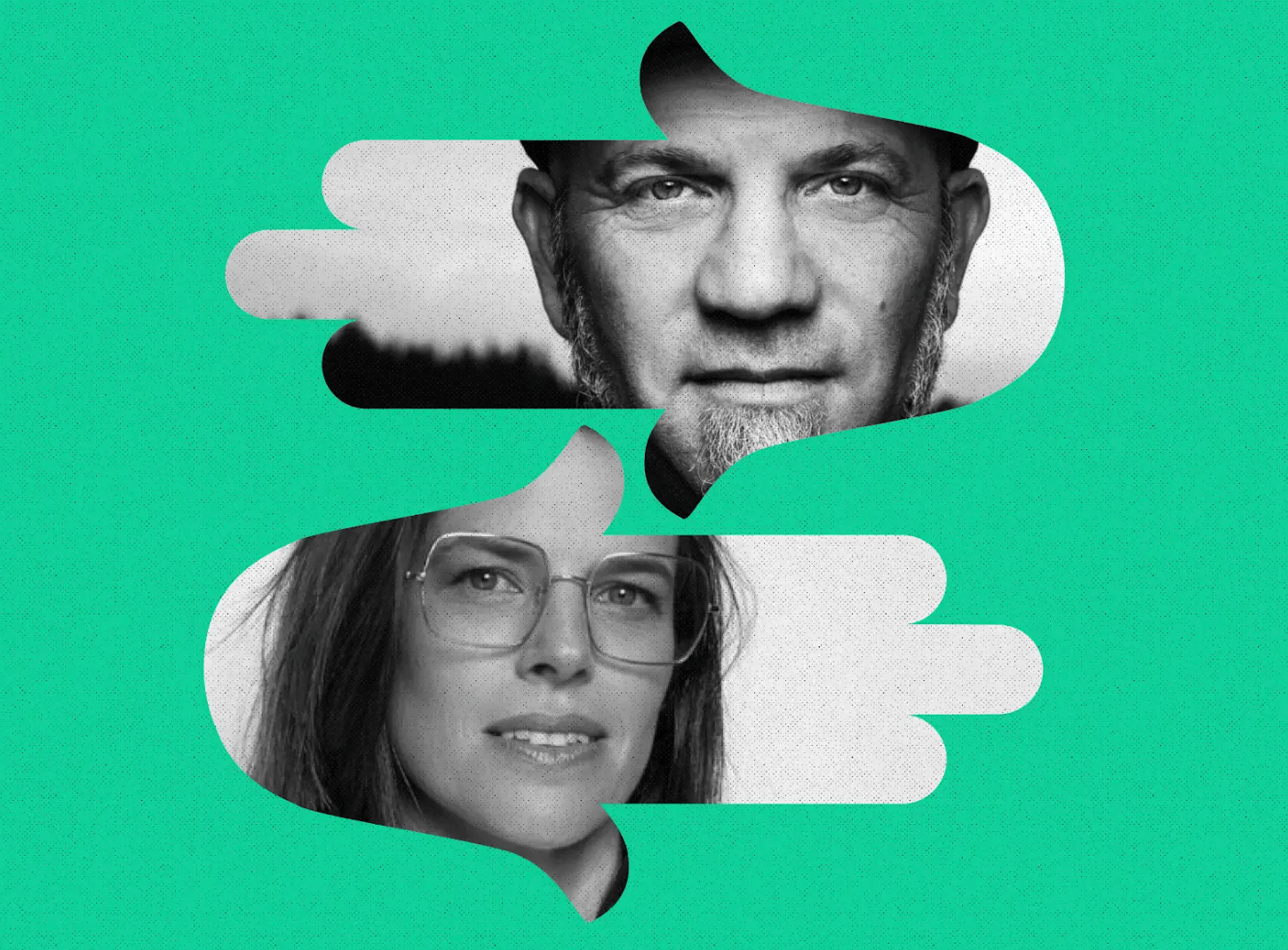

The Israeli hip-hop artist Shaanan Streett (top) is the first guest on Make Art Not War, a new podcast hosted by Libby Lenkinski (bottom). (Tamar Lazaros/Laba Media House)

Was it a memory or was it a mirage? Shaanan Streett, the Israeli hip-hop artist, wasn’t sure.

He was a soldier in Gaza that first day of November in 1991. But it was so long ago. Not in terms of time — three decades is a heartbeat in the history of the Holy Land — but trauma: Before the Israel-Hamas wars. Before, also, Oslo and Camp David. Before Netanya and Jenin, before Yigal Amir and Baruch Goldstein; before, way before, Oct. 7.

“So little has changed for the better, and so much has changed for the worse, that I wasn’t even sure that my memory was correct,” Streett said as he shared the story on our new podcast, Make Art Not War.

Nov. 1, 1991, was four years into the First Intifada, or Palestinian uprising. Every day, Streett said, Gaza residents threw stones and bottles at him and other members of the Israel Defense Forces as they patrolled the streets. Sometimes, molotov cocktails. Once, in an alleyway at night, he said, “somebody pushed a refrigerator from the roof and it fell about a meter behind me, but I kept walking.”

Nov. 1, 1991, was also two days into the Madrid peace conference. The television showed Israelis, Palestinians, Jordanians and Syrians sitting together. And in Gaza, according to Streett’s fading memory, residents threw not stones or bottles but flowers and rice and olive branches.

“Am I sane? Did this day exist?” he asked. “Because if it did, why isn’t it at all in collective memory?”

Wikipedia, he noted, records “every terror attack that happened, and it’s good that we know it; I don’t want to forget it. But if there were opposite things, why are those lost in our collective memory? Why can’t we remember and build on the good things that happened, the hopeful things that happened? Why can’t we bite the bait of peace? Why is it always us biting the bait of war?”

Streett, 53, is the longtime lead singer of Hadag Nahash and featured in today’s launch episode of Make Art Not War, a show hosted by Libby Lenkinski, an Israeli-American focused on how art can promote peace. The podcast, which the Forward is producing in conjunction with Libby’s new organization, Albi, is straightforward yet profound: conversations with 10 Jewish and Palestinian creatives working in Israel about their art and their lives in the aftermath of Oct. 7.

Future guests include Mira Awad, the Palestinian singer who once represented Israel at Eurovision; the writer Etgar Keret; comedian Noam Shuster-Eliassi; the street artist Addam Yekutieli, aka Know Hope; Neta Weiner and Samira Saraya of the Jewish-Arabic hip-hop ensemble System Ali; and Ohad Naharin, the former director of the dance troupe Batsheva.

Libby asks her guests to reflect on a quote from Jonathan Larson’s musical Rent: “The opposite of war isn’t peace, it’s creation.” Streett said it reminded him of another quote, by Emma Goldman, that Hadag Nahash had used in a song: “If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution.”

“You know, creative people, they’re thinking about the future, even if they don’t realize it,” he explained. “They’re being optimistic somehow, even if the creation itself is not very optimistic. If it’s sad, if you’re writing a sad song — if you’re writing a sad poem, whatever — the fact that you’re writing it, there’s something happy in that. There’s something optimistic in that.

After Oct. 7, Streett and Hadag Nahash gave free concerts for survivors from the Nova festival, evacuees from the destroyed kibbutzim in the south and the threatened communities near the Lebanon border, deployed soldiers and others. For months, he kept a journal, but didn’t write any songs.

And then “after like three or four months,” he said, “I just couldn’t stop writing songs.”

One of Streett’s new songs is called “Charbu Darbu” — Hebrew for “Connect and talk,” but also a pun on the post-Oct. 7 Israeli hit “Harbu Darbu” — “have war with” by Ness & Stilla. Another is “Zayin b’Oktobe,” Hebrew for the date of the Hamas attack, and also a pun on, well, the penis. (Or, as Libby puts it in the podcast, “a dude’s downstairs parts.” Nice.)

The song about that day in Gaza in 1991 is called “Waltz with Shaanan,” a nod to the legendary 2008 Israeli animated film Waltz with Bashir, which is about post-traumatic stress among soldiers who fought in the 1982 Lebanon War.

Streett’s song recounts the horror of the first intifada — “a 5-year-old boy killed with a bullet meant for his feet,” a commander’s teeth knocked out by a rock, that refrigerator thrown from a rooftop. And then, as he puts it, “a story you haven’t heard before.”

Because the same streets where we saw protests and arrests

Suddenly filled with a sea of celebration and shouts of happiness

The same hands that stoned us in past circumstances

This time threw rice, candy, and olive branches

Uniformed soldiers, in a cheering crowd on the main street

We didn’t know what to think, we didn’t want to agitate

But it happened, and I was there, the moment when a message, distinct and clear

Was supposed to be sent, but it never arrived, it’s not here.

(English translation by Gabe Selgado, courtesy of YouTube)

“Waltz with Shannan” grew out of an encounter Streett had with the top generals of the IDF. He’d been invited to perform a few songs for them and their wives on a Friday in Jerusalem. First, he asked about his muddy memory, figuring “these guys were in the army forever” and might know whether Palestinians indeed gave soldiers flowers that day.

One said that he, too, had been in Gaza, and remembered “people running up to my Jeep and sticking olive branches into the Jeep,” Streett told Libby. Another general said he’d been on duty in the occupied West Bank, and “it happened there, too.” A third said he had a roll of black-and-white film documenting similar scenes.

When Street headed to his car after a post-show beer in the green room, the IDF chief of staff was waiting for him, along with his wife and two bodyguards. “He says, you know, you need to write a song about this story,” Streett recalled. “And you should call it, ‘Waltz with Shaanan.’ So I did. You know, I’m a soldier, I do what the general tells me.”

The song actually came out in September 2023, but it took on new life after Oct. 7.

“I think the most moving responses that I got were from soldiers in Gaza in this war,” Streett said on the podcast. “Even they feel like I understand them, even though it’s 100 times worse now. Our guys in Gaza now, you know, what they’re going to have to deal with is a hundred times worse than what my generation had to deal with. But still they feel that somebody understands them.”

That understanding, Libby responds, is one of the things we know art can do. In wartime — and all the time.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO