How one of America’s most prominent rabbis got on the path to the pulpit

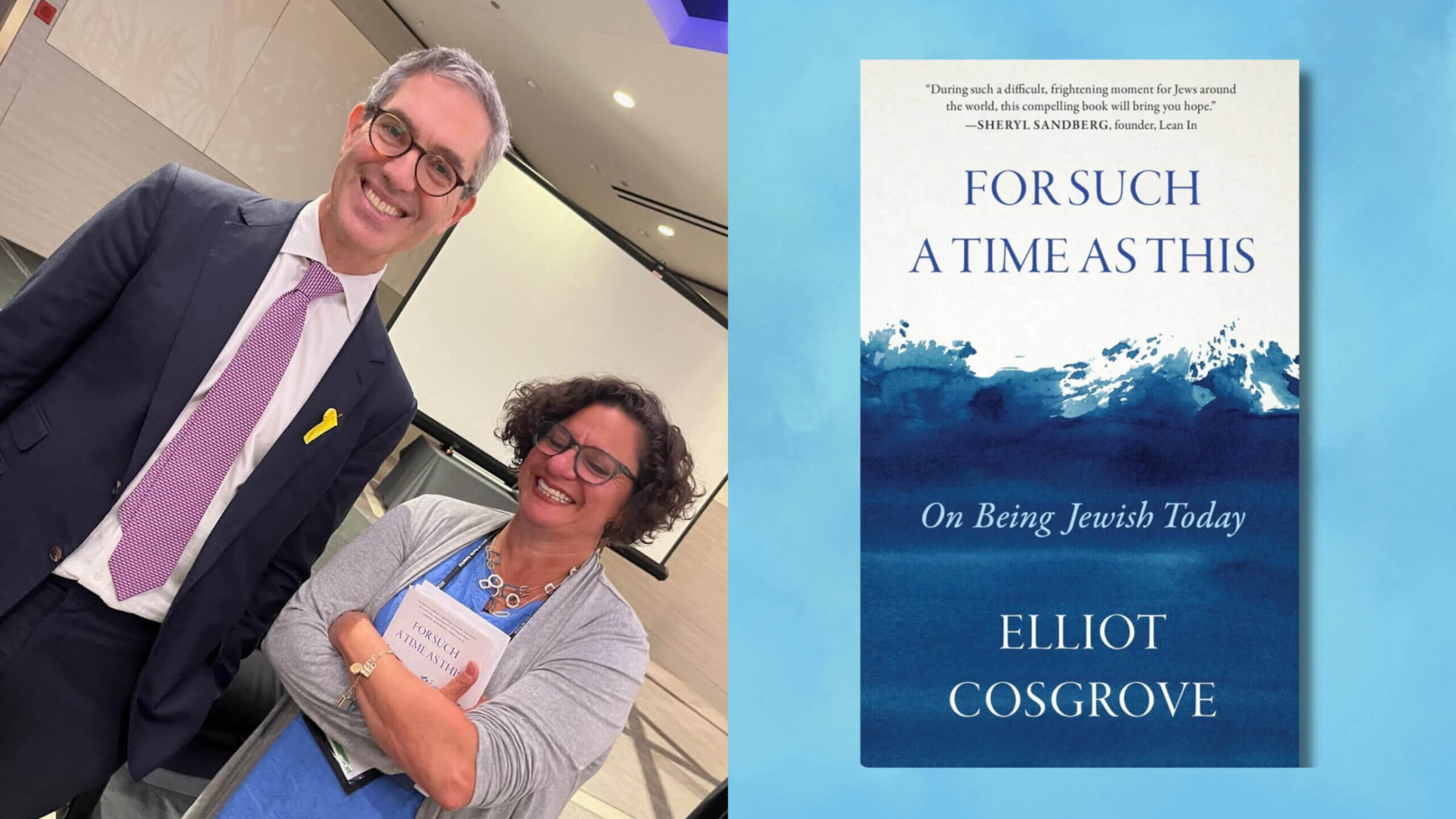

In a new book, Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove meditates on what it means to be Jewish in “such a time as this”

Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove and the Forward editor-in-chief Jodi Rudoren chatted about his new book at the JCC Association conference in Chicago on Monday. It comes out next week. Photo by Rachel Fishman Fedderson

I’ve been friends with Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove for more than two decades. He officiated at my 2004 wedding in Chicago, and counseled me through the termination of a traumatic pregnancy. I helped him shape the first op-ed he ever got published — way back in 2006, about the new chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary — which he credited for helping him get his current gig leading Manhattan’s Park Avenue Synagogue, where I have spoken several times.

I’ve been to Elliot’s home for Shabbat dinners. I know his kids (they’re lovely). I’ve heard him tell the joke more than once about how he’s the let-down in a Jewish mother’s dream family, with brothers who are a doctor, a lawyer and a Hollywood mogul. (When he was with the Pope at the Ground Zero memorial, his physician-brother texted the family group chat: See that guy standing next to the Pope? His brother’s a doctor!)

Which is why I was surprised to realize, as I read the rabbi’s new book, For Such a Time as This, that I’d never asked him how he ended up on the pulpit in the first place. It turns out to be a really good story.

For Such a Time as This is a compact little book — “This year’s must-have for your tallis bag!” Rabbi Cosgrove told the folks who came to hear us talk about it at the JCC Association convention in Chicago this week. The title comes from the Megillat Esther: To convince the queen to intervene to thwart Haman’s plot to kill the Jews, Uncle Mordechai suggests that perhaps the whole reason she ended up in the palace in the first place is for such a time as this.

Heady stuff, and the broad implication, in a book being published a year after Oct. 7, is that we, like our forbears, are in a perilous moment and should, like Queen Esther, embrace our Jewishness to save our people.

Maybe. But as I read the book, I found myself thinking also that people throughout history have probably always considered theirs a particularly fraught or auspicious time. How many politicians have told how many crowds that the coming election was the most important of their lives?

So maybe “for such a time as this” is not about a particular moment but about all the moments. Maybe our fundamental obligation is to make what we can of the moments we have. Which brings us back to Elliot’s rabbi-origin story.

A fateful Friday

It comes practically at the end of the book and plays out over a quick few paragraphs. He was a junior at the University of Michigan, not “terribly involved in Jewish life,” he writes, when his parents called to tell him about the death of Mr. Gendon, “a grandfatherly figure” he’d sat next to in synagogue growing up in LA. “Not really knowing what to do but knowing I had to do something,” Elliot writes, “I decided to go to the Friday night service at Hillel to say kaddish.”

He’d only previously been to Hillel for the High Holidays, and knew no one there. So he sat through the service, said kaddish, and was bolting for the door to meet his friends for Dollar Pitcher Night when “a man blocked my escape route,” as he puts it, to ask if he had plans for Shabbat dinner.

Young Cosgrove lied and said he did. The man — it turned out to be Michael Brooks, who ran Michigan’s Hillel for more than three decades — “then said something that I will never forget,” Elliot writes. “It changed my life forever.”

Well, I bet you don’t have plans for next Friday night.

It worked. “The following week I went back to services and Shabbat dinner,” Rabbi Cosgrove recounts. “I went again and again, became a Hillel board member, led a pro-Israel group to Washington, D.C., edited the Jewish student journal, went to Israel, went to rabbinical school, got a doctorate in Jewish history, and — to make a long story short — became who I am today.”

The retail rabbinate

I’ve never met Brooks. Elliot told me that he changed thousands of young Jews’ lives in this kind of one-on-one, seize-the-moment, don’t-take-no-for-an-answer sort of way, and writes in the book that his “example of personal leadership remains the bar to which I continue to aspire.”

Though he now heads one of the nation’s most prominent synagogues, speaks at major rallies and raised millions of dollars for Israel in the days after Oct. 7, Elliot says being a rabbi is at its essence a “retail” job. Person-to-person. What matters is what happens when someone comes to see him in his office, to talk about conversion or intermarriage, about anti-Zionism or antisemitism, about “being Jewish today” — the subtitle of his book.

For such a time as this. I’m no Esther, but I did feel, in the months after Oct. 7, that I was in the right place at a terrible time to use my experience in ways that were meaningful for our communities.

I’m no Brooks or Cosgrove, either, but I also think about our journalism as a series of retail encounters with individuals. It’s why I answer all the email I get from readers — regardless of how angry or frustrated or saddened they are by something I’ve written — and why that’s one of my favorite parts of the job. All those little moments, fraught and auspicious.

What’s so powerful about Elliot’s Hillel story is not that Brooks invited him to Shabbat dinner, but that he didn’t take no for an answer. When Brooks asked about “next Friday night,” Elliot writes, “I shrugged sheepishly.”

“Good,” Brooks responded. “So I will see you then.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO