What’s really behind the sanctions on Israeli settlers and UNRWA

How to understand two seemingly bold Biden administration steps to crack down on terror in the Middle East

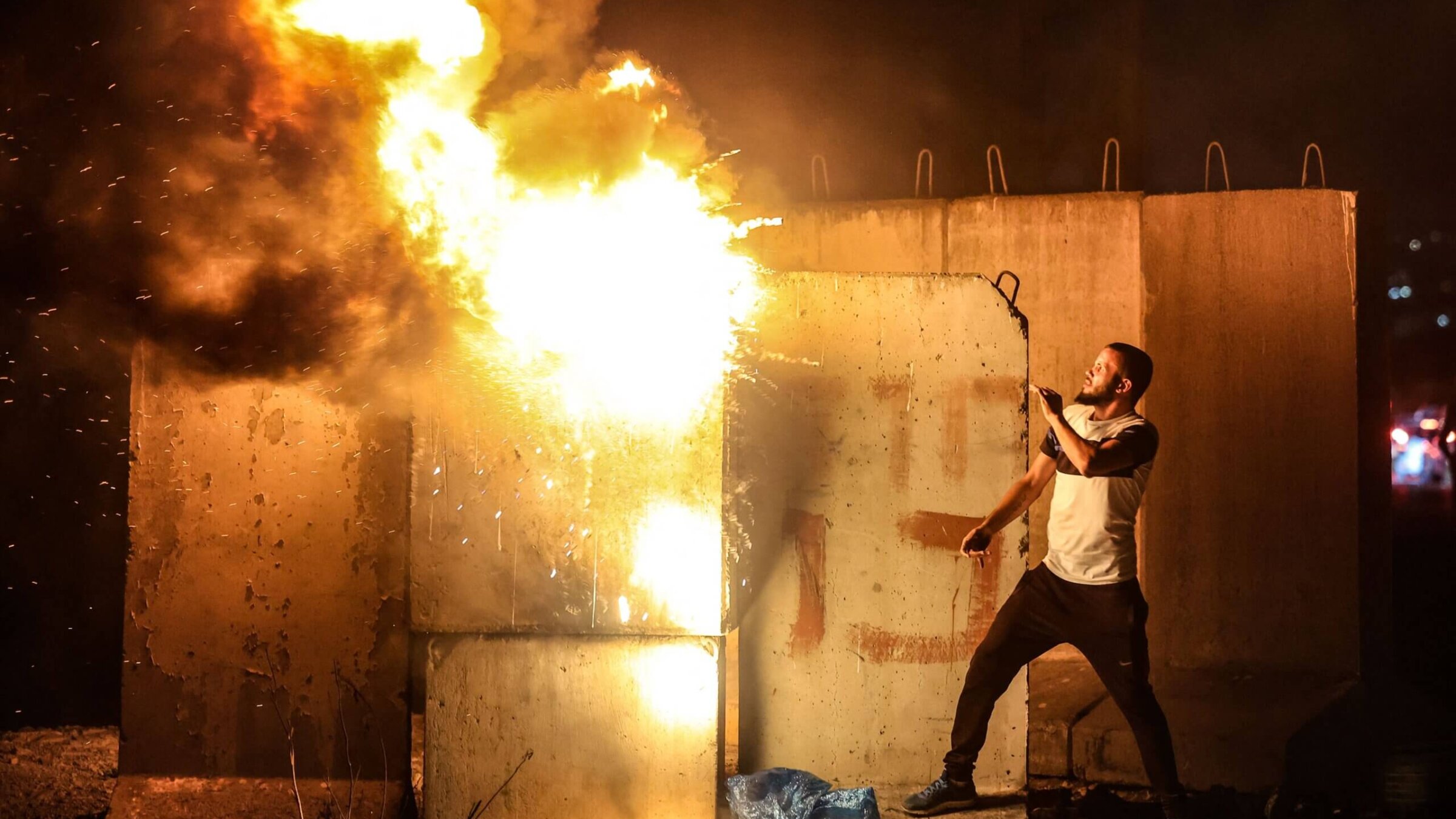

A Palestinian demonstrator during confrontations with Israeli security forces at the Israeli Hawara checkpoint near the West Bank town of Nablus following a rally in support of Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli jails, on September 8, 2021. Photo by JAAFAR ASHTIYEH/AFP via Getty Images

This week’s news was bookended by two seemingly bold Biden administration steps to crack down on terror in the Middle East: suspension of funding for UNRWA, the Palestinian refugee agency, and sanctions against violent Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank.

My first thought after reading Thursday’s executive order regarding the settlers was: too little, too late. It affects only four men, comes nearly a year after the horrific pogrom in the Palestinian town of Huwara, and does not directly address the eight murders and some 500 attacks in the territory since Oct. 7.

Meanwhile the response to the revelations that a dozen UNRWA employees had joined the barbaric Hamas terror attack on Israel felt like overreach at exactly the wrong time. The world is already outraged at the death toll, destruction and displacement Israel’s military has wrought on Gaza. What if defunding UNRWA, the main provider of food and shelter there, pushed the humanitarian crisis past the brink?

It turns out that, like so much of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, things are not always as they seem.

“It’s a lot of political signaling and not a whole lot else,” a Washington expert on the Middle East who I trust explained to me last night. “There’s no money affected and no people affected. It’s caused a lot of sturm and drang and got everybody’s heads spinning, but it’s a lot more about the signals than the impact.”

It’s always dicey to compare things in this hopelessly asymmetrical conflict. A rabbi I reached out to about this said UNRWA and the settlers were like “apples to bicycles.” But it’s also essential to look at the whole situation. And I couldn’t avoid the parallels.

In both cases, you had a handful of (very) bad actors — four settlers, 12 UNRWA workers — within a much larger group. Both larger groups — about 500,000 Israelis in the West Bank, 13,000 UNRWA employees in Gaza — have long been demonized by the other side as prime obstacles to peace.

And both undoubtedly contain more bad actors — The Wall Street Journal reported that Israel has evidence of 1,200 UNRWA-Gaza workers with ties to Hamas; human-rights groups have documented hundreds of settlers terrorizing Palestinian farmers — as well as many members who are upstanding citizens.

Most Israeli settlers, after all, are not gun-toting zealots but families who moved to the West Bank because it is quieter and cheaper than Israel’s crowded main cities. And UNRWA is one of the largest and most stable employers in Gaza — most of its employees, like most Palestinians in Gaza, dislike Israel but are not actively trying to destroy it.

A colleague pointed out, too, that both the settlements and UNRWA were supposed to be temporary, like Israel’s occupation itself, and have instead calcified into massive roadblocks to the two-state solution.

So how is it OK to have a narrow, targeted punishment for the violent settlers, affecting only a few individuals and not the the leaders and system that spawned them — and what sure looks like collective punishment against not only UNRWA and its employees but the 2 million Gaza residents they’re serving right now?

I ran all this past Michael Walzer, the preeminent philosopher and author of the 1997 book Just and Unjust Wars.

“I don’t know what the U.S. can do besides condemn what’s going on there,” he said of the West Bank violence. “Maybe it would have been right to sanction the ministers who are in charge of the West Bank. That would have been much more dramatic, and it would not have been collective punishment; it would have been direct and specific.

“I think that is determined by politics,” he added, “and not by any kind of moral evaluation.”

Which is what led me to call my trusted Washington friend, a liberal Zionist who has lobbied Congress and the White House for nearly two decades and, like too many people in politics, spoke on the condition of anonymity so he could be frank. “This is virtue signaling,” was how he began.

I’ve covered politics off and on for 30 years, so I like to think I’m not totally naive about these things. I certainly knew instantly, as we and everyone else reported, that Biden’s executive order on settlers was purposely timed during his visit to Michigan, a critical swing state with a large Arab American population, in hopes of appeasing left-leaning Democrats critical of his staunch support of Israel throughout the war.

But it seems my instinctive cynicism may have gone soft. My Washington friend broke it down in a heartbeat: The UNRWA suspension wasn’t nearly as harsh as it looked, and the settler sanctions had more scope than it seemed.

The State Department, as The New York Times reported on Tuesday, has already sent UNRWA 99% of the $121 million in the current U.S. budget allocation, so Biden’s move only deprives the agency of $300,000. The real issue is whether UNRWA will be funded in the next round of appropriations, with votes expected in the coming weeks as the continuing resolution funding the U.S. government through February runs out.

My friend said that the White House wants to keep funding UNRWA, and needs the votes of centrist pro-Israel Democrats and Republicans to do so. So the defunding was a gesture to show them that Biden takes the problem of UNRWA helping Hamas seriously — and to pressure the U.N. to crack down on it.

He also pointed out that Israel doesn’t actually want UNRWA defunded, because then Israel would be pressured to take on direct responsibility for feeding and sheltering Gazans the war has displaced. And — this should delight your inner cynic, and may require a little diagram — that there was already a backstop plan: If the U.S. does not get UNWRA funding in the next budget, he said, European countries will move aid from the less-controversial World Food Program to UNWRA and have the U.S. backfill the World Food Program.

So UNRWA is not about to shut down operations in Gaza. Phew. Now, on to the settlers.

While only four men were named in the State Department release on Thursday, the executive order lays the groundwork for sanctions against the ultra-nationalist ministers in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government and leaders of the settler movement that have seeded the spike in West Bank violence. An analysis in Haaretz today called the executive order “a game-changer” that “could irreversibly alter the West Bank settler enterprise.”

After literally decades of the same mealy-mouthed statements from Washington about settlement expansion being an obstacle to peace, the sanctions are an unprecedented step in the right direction. Both because they move from statement to action, and because they define settler violence as not just an Israeli-Palestinian problem but, as a White House spokesperson put it, a threat to “U.S. national security and foreign policy interests.”

So what looked like a scalpel, my Washington friend said, was really “a loaded gun sitting on the table.” The executive order could even trigger a break between Netanyahu and the far-right settlers in his coalition — which could spell the end of his reign.

“Both of these things are about signaling — they both are attempts to shape future policy by other actors that you don’t have a lot of power over,” my friend said of Biden’s UNRWA-settler two-step.

“There’s nothing wrong with signals,” he added. “Politics is about signals.”

Walzer, the philosopher, had raised an important point during our conversation about what the parallel move to defunding UNRWA would be concerning the settlers. The United States has long restricted the use of its loan guarantees and grants for absorbing immigrants to within Israel’s pre-1967 borders, and last summer the Biden Administration reinstated a rule preventing U.S. money going to academic institutions in settlements.

But the bulk of U.S. funding for Israel, $3.8 billion a year, is for Israel to buy weapons and other military equipment from American manufacturers. That money is not given to settlers who uproot Palestinians’ olive trees or torch their towns, but it does help fund the occupation.

“Is the bulldozer that is demolishing the village paid for with our tax dollars? We don’t know,” my friend said. “If you see a soldier standing over a Palestinian, about to shoot them, and that gun was made in the U.S., chances are it was paid for by us.”

I’m glad I got schooled on this. I didn’t want to think that Washington was being softer on Israeli settlers and harder on starving Gazans.

I hope every UNRWA worker who participated in the Oct. 7 attack is sent to prison and their bosses are all fired. And then I hope Congress keeps funding the agency.

I also hope the State Department indeed expands the sanctions to include more violent settlers and the politicians who incite them.

And I hope that amid all the political signaling we don’t lose our moral compass.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO