Every soldier has a mother. And each has her own story.

How to tell a war story when you don’t know where to start.

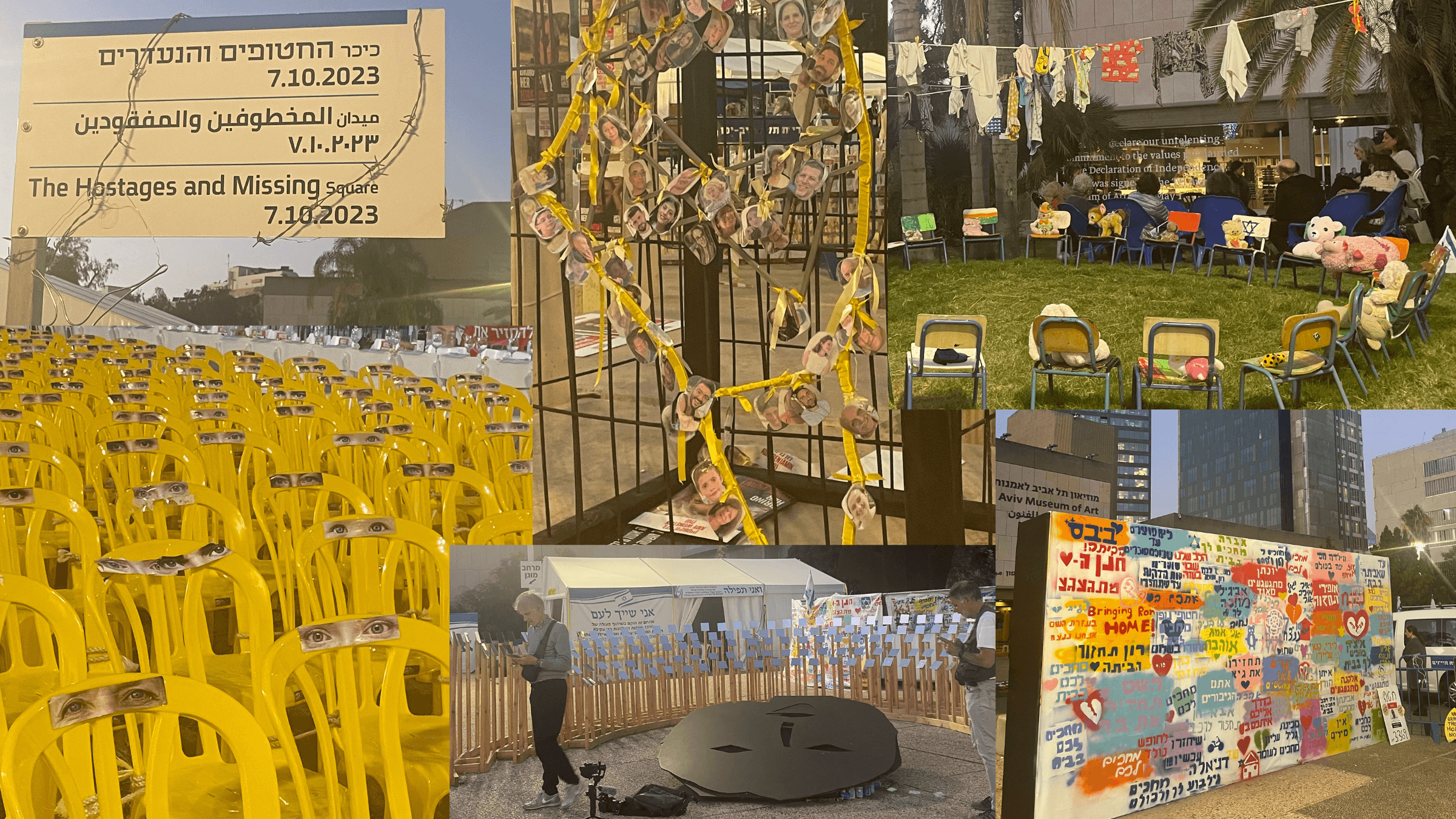

A variety of tributes at Tel Aviv’s Hostage Square. Photo by Jodi Rudoren/Collage by Odeya Rosenband

JERUSALEM — When Orit Avnery, an Israeli rabbi and Bible professor, said she was unsure where to start telling her war story, I thought she meant before or after Oct. 7. Before or after the weeklong pause in Israel’s current war against Hamas that ended this morning. Before or after more than 100 hostages came home.

I was thinking way too small.

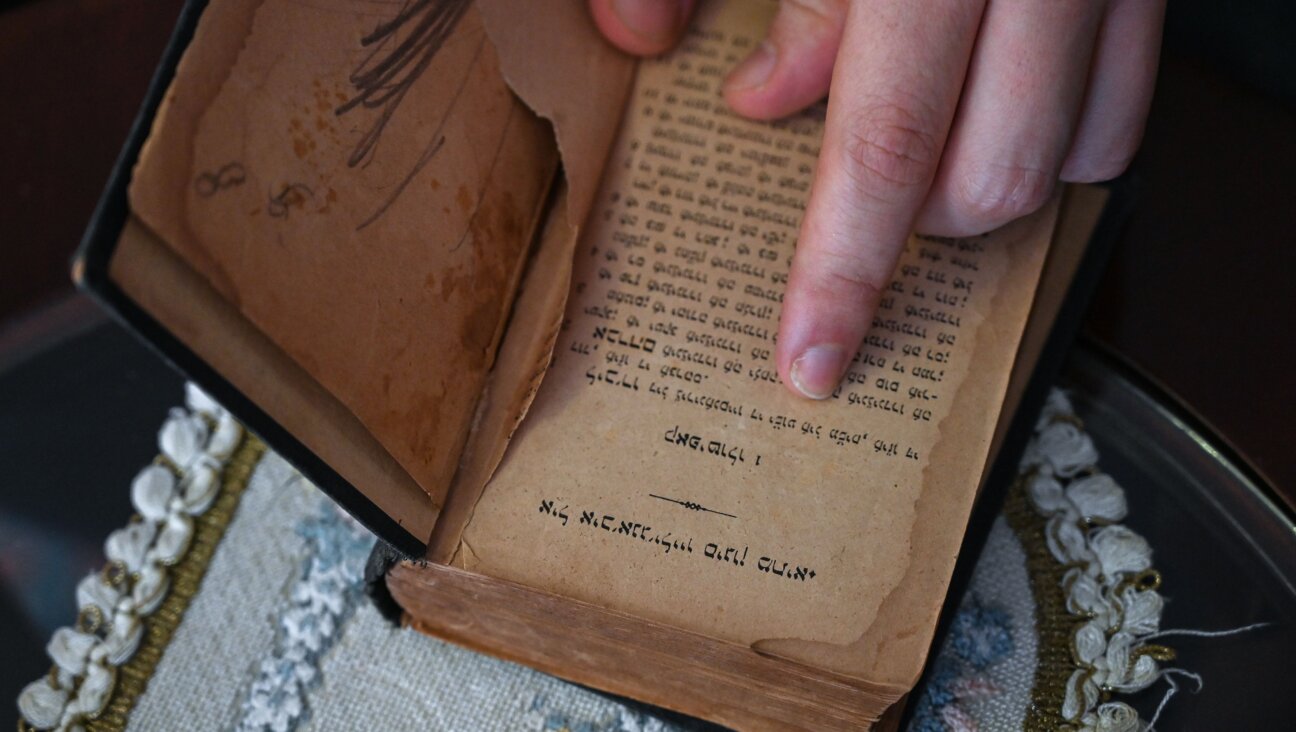

“It’s a question for everyone — where to start,” Avnery told a group of visiting American rabbis at Jerusalem’s Shalom Hartman Institute Thursday. “In your life now, in your parents’ life, in your grandparents’…

“In Avraham, in Bereishit,” she continued, referring to our Jewish patriarch and the opening chapter of the Torah. “We are now thinking about how to tell the story, how to frame the story, what is our story. For the Israeli people, for the Jewish people: How to tell our story. Where to start?”

Avnery decided on 50 years ago. She was 10 months old when her 24-year-old father was killed in the Yom Kippur War. Now, she has a grandson who is 10 months old, and his 24-year-old father — her son Yuval — is among the 300,000 Israel Defense Forces reservists mobilized for this war.

Four of Avnery’s five children are in uniform right now. The 22-year-old, Noam, is fighting inside Gaza with Givati, an infantry brigade.

“So, you know, history is coming back,” she said. “After 50 years, we are in the same place — and even worse.”

The difficulty of painting the full picture

As a journalist, I am always obsessing about where to start a story. We call the opening sentence of each article or column the “lede” — old newspaper hands spelled it that way to avoid confusion with the “lead” of printing presses — and we know it’s the most critical piece of each article or column. We know, especially now that most of you read news on your phones, that you will click away if the lede is not compelling.

Covering the Israeli-Palestinian conflict gives this dilemma new dimensions. Before this horrific war between Israel and Hamas, there was one in 2021 — and 2014, and 2012 and 2008-9. Maybe we should start the story in 1967, when Israel seized Gaza along with East Jerusalem and the West Bank. Or why not in 1948, with the establishment of the modern Jewish state. But what about 1929, when Arabs massacred scores of Jews in Hebron?

Soon, as Avnery said, we are back at Avraham and his two sons, Isaac and Ishmael.

I could start this first dispatch from my first trip to Israel since Oct. 7 with the first moments after I landed Wednesday at Ben-Gurion International Airport. The signs everywhere pointing to “Shelter,” as in bomb shelter, were not there when I lived in Jerusalem a decade ago. The walkway to Passport Control is lined with hostage posters — and, thankfully, there are now many empty spaces that used to hold the names and faces of those who have been freed.

I could take you to the plaza outside the Tel Aviv Art Museum, officially renamed Hostage Square a few weeks ago, to see the many interpretive tributes to those 240 people ripped from their homes. The long Shabbat table of empty chairs, of course, but also a semicircle of wooden posts with silver plaques, called “Pieces of Light,” that the artists who created it say is “a reminder that hope, like light, will never stop to shine.”

A clothesline hung with tiny garments over a circle of colorful preschool chairs holding worn stuffed animals. Photos of the hostages tied together with yellow ribbons in a shape evoking Israel’s map. A chessboard where each piece is blindfolded. Metal hearts hanging under what looks like a wedding canopy. Papercut pomegranates strung from a tree.

But on this day that the pause in fighting ended, it seemed appropriate to start with Avnery, since every soldier — like every hostage and every person killed on both sides — has a mother.

“To be a mother to a son is that you feel it from the womb,” she said as she told us how Noam deployed on Oct. 8 and has since only been home once, for two days. “When I took him to go back in the morning, I thought, ‘How can it be?’ It’s really not normal that I, as a mother, can let him go, because our instinct is to make sure they are safe.”

Avnery, who teaches at the Hartman Institute as well as Shalem College, was part of an intense, three-day immersive tour for some 30 rabbis from across the U.S. and Canada.

One participant told me she hesitated about whether to join the trip, not wanting to be voyeuristic; Israelis are already arching their eyebrows about trauma tourism. Hartman billed the program as a volunteer mission — and they did help pick olives at an Israeli farm and make food for deployed soldiers, visit the injured at a Jerusalem hospital and kibbutz evacuees at a Dead Sea hotel.

But the rabbis said the program turned out to be more about witnessing, about hearing the stories, wherever they began.

‘We’re all one family’

Speaking alongside Avnery on Thursday morning were Ayala Deckel and Renana Ravitsky Pilzer, whose husbands are both deployed reserve officers.

Deckel, who runs Bina, an Israeli movement combining study and social activism, said that she did not tell her three children — who are 14, 12 and 10 — that their father, Yonatan, was inside Gaza. But five weeks into the war, on his birthday, he managed to find a tall building where he could get cell service from the rooftop, and sent a selfie to the family WhatsApp group that showed the destruction behind him.

The kids erupted. “My older one came to me and told me, ‘I’m the one who is supposed to help you! How can I help you if you don’t tell me the truth?’” Deckel recalled. The youngest reassured the middle one, she added, saying: “Mom told me she did not let him fight, he can only guard the soldiers. He will never do what mom told him not to do.”

Yonatan was home for three days, and spent the first going to visit wounded soldiers in the hospital and families of the fallen. She went with him.

“Each and every soldier knows what happened to him, but they don’t know the whole story,” Deckel explained. “So he told them. We went from a room to a room to a room. After that we went to Beit Aveilim, to people who lost their kids. You see your husband standing, telling story after story; hundreds of people sit around and ask him questions.

“We’re together, but we’re apart,” she continued. “I told him at the beginning, I don’t want him not to tell me something because he wants me to feel safe. We need to keep our kesher zugi” — connection as a couple — “even though we cannot talk every day or every week even.

“The third day he was at home, I started to cry,” Deckel added. “He started to do the dishes, and he went to buy me a present, and I started to cry, and he said, ‘I can’t have you like that, be strong. My responsibility as a wife and as a mom, I need to hold the whole world, because everything is falling apart.”

Pilzer, who works at Hartman’s center for Israeli and Jewish identity, has two daughters in the army as well as her husband; one of their boyfriends is inside Gaza. One of his friends brought out a video of him playing a guitar they’d found, as bombs went off in the background.

“They’re sitting there smiling and singing,” she said. “You can hear the war from outside, and they’re as if they don’t hear it. It was so frightening to see how they got used to it, how they don’t hear it, they can protect themselves.”

Pilzer’s husband, who is 50 and working on bases inside Israel, has come home several times for a few hours or a few days. “What is the first question I ask him when he comes? I say, ‘How long do you have?’” she told us. “Because I’m not sure I want to open my heart, I’m not sure I want to take down the wall.”

Their lives have meanwhile been reordered. Pilzer said she has learned to say “yes” when neighbors offer to bring dinner or when a spa offers free massages for the wives of miluimnikim, Hebrew slang for reservists. Deckel is struggling to square her feminism with her current role.

And Avnery, who before Oct. 7 was the kind of organized person who would write in her planner today what she’d be doing a year from now, now understands that “I don’t know what will happen tomorrow, I don’t know what will happen next week or next month, and for me that’s really hard.” When she is home, she runs to the window when she hears a car stop outside, hoping it will not be people in uniform coming to knock on her door.

“We all are relearning how to walk, like a baby,” Avnery said, referring to all Israelis. “The problem is that I can’t tell them not to go, because I feel we are really in a fight against the darkness, against the evil, against something that we cannot live with.

“I want them to do it — but not my son to do it,” she added, referring to Israel’s stated goals of eliminating Hamas and bringing all the hostages home. “But we’re all one family.”

These days, Avnery spends much of her time trying to calm her anxious daughters-in-law, and helping feed and play with her grandson, Marom.

I wonder what story he will be telling 50 years from now, where it might start.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO