This is our editor-in-chief’s weekly newsletter. Click here to get it delivered to your inbox on Friday afternoons. Etgar Keret was walking along Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff Street the other day when he saw a father yelling at his son. The boy was about 6, and he was imitating the sound of the Red Alert siren that warns of rockets coming from Gaza.

“The father was saying, ‘Stop, you’re scaring people,’” Keret recounted. “The child didn’t understand what was going on. He was just imitating this noise he kept hearing all the time. The father snapped at him. “The father couldn’t see the child in this moment,” he continued. “You have this big story. But you also have the human, personal story. It’s so easy, in this moment, to forget your story and kind of drift with this kind of national catastrophe and kind of disappear in it.” I reached out to Keret, our generation’s best-loved Israeli author, Thursday because I felt myself getting fatigued by the big story — overwhelmed by the emotional interviews about hostages, tired of the talking heads, dizzied by the despicable lies drowning social media. Keret is Israel’s bard, a remarkably prolific producer of short fiction and essays and films and children’s books and graphic novels — and also a person whose casual observations land like poetic prose, even in his slightly broken English. He was born in 1967 to Holocaust survivors from Poland. We first met him in 2012, shortly after I began my tour as Jerusalem bureau chief of The New York Times, bonding over the fact that our sons were both named Lev, the Hebrew word for heart. I like to call him when I need a sense of the Israeli street, the Israeli soul. I didn’t ask “Are you OK?” because I know no one is OK. “What I feel is that we’re usually a very complex network of contradictory emotions in some kind of balance,” he began. “We love somebody but we’re a little jealous of them. And we’re a bit attracted to them, too. But we’re also afraid of them — there is a very, very intricate web. “A situation like this, we become one emotion: We’re in despair, we want vengeance, we’re afraid. “Usually when there is a terrorist attack, you tend the wounded,” he continued. “But here it seems everybody is wounded. You see somebody in the street, and you say ‘Let’s have a coffee,’ and you feel like you’re helping somebody.” |

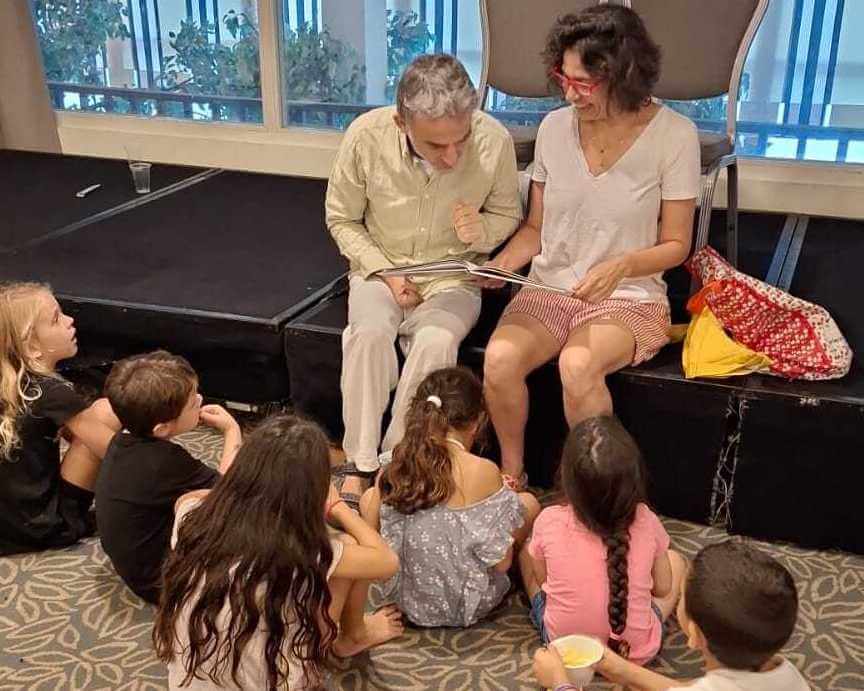

Etgar Keret, Israel’s bard, talking to soldiers this week. “Every day I’m somewhere else,” he said. (Courtesy) |

Keret has not written a new story since the war began, which is unusual for him; he typically produces several a week. He has instead been giving impromptu readings — to children who survived the Hamas massacres at the border communities of Kfar Aza and Nir Oz; to soldiers awaiting deployment to the front; at a retirement home where some had numbers tattooed on their arms; over Zoom to people stuck in their safe rooms because of the ongoing barrage of rockets from Gaza. It’s not organized; he just shows up, gives out books, offers to talk, listens. A friend with young children shaken by the frequent rocket sirens went overseas for 10 days, and feels guilty, Keret said, “So one of my chores is to send them WhatsApps saying, ‘It’s cool, it gives Hamas one less target.’” I asked why he isn’t really writing yet. “There’s something about it that is undigestible,” he said. “I think that when you write a story, you feel that your gut knows something even though your brain doesn’t yet understand it,” Keret explained. “Right now, I don’t even feel that my gut got it.” As he is going around, if he feels a connection with someone, he invites them to a WhatsApp group where, every couple of days, he is posting unpublished stories he wrote before the war. He is also jotting tidbits into the Notes app on his iPhone between stops (he does not drive). He read one he called “Signs of Life” aloud yesterday on NPR’s Morning Edition. Now close your eyes, and try to stop being angry. Try to stop raging at all those who deserve your righteous fury. Close your eyes, and allow yourself, just for a moment, to simply feel the pain, to hesitate, to be confused, to feel sorrow, remorse. You still have your whole life to spend persecuting, avenging, reckoning. But for now, just close your eyes and look inward like a satellite hovering over a disaster zone searching for signs of life. A lot has been taken away from you, but you’re still a human being — wounded, bloodied, angry, hurting, frightened, drowning in sorrow, but still human. Take a deep breath, and try to remember the feeling. Because you know that, a minute from now, when you open your eyes again, it will be gone. I asked how he is sleeping, what he is eating. Keret is an insomniac but said he has actually slept better since the war. “My explanation is that I’m so exhausted when night comes,” he said. “It’s not like a normal day. Every place you go, you stop because there is a missile attack. I hardly eat because I’m all the time moving.” |

“I think that when you write a story, you feel that your gut knows something even though your brain doesn’t yet understand it. Right now, I don’t even feel that my gut got it.” |

– Etgar Keret, Israeli author |

There has been a lot of talk about how small and interconnected a society Israel is. The murder of 1,400 people in a single day, given the population of 9 million, is comparable to 17 times the losses the U.S. suffered on 9/11. (All the more so in Gaza, whose population is even smaller, some 2.3 million, and death toll higher, more than 3,700 since the start of the war, according to the local health ministry.) Everyone I know in Israel has somebody they just buried, somebody presumed abducted, somebody deployed. Keret’s day-to-day made it all the more human and real. “I go to somebody’s house and his internet doesn’t work, and he says, ‘Use my neighbor’s,’ and he gives me the password and he says, ‘My neighbor right now is kidnapped,’” he said. “You meet the cashiers at the supermarket and all of them, they lost somebody, they have somebody right now missing, they have somebody in Gaza.” The roads are empty, Keret told me, and Dizengoff quiet, bars and restaurants closed because the 20-something waiters and cooks and barbacks have been called to reserve duty. “On my street there is a car parked in a place where you’re not supposed to park,” he said. “There is a note on the windshield saying, ‘Sorry, supervisor, I was drafted, please don’t write me a ticket.’” There have been a million people saying a million things about why this war is different, why Oct. 7 shook Israel like nothing before. The size of the losses, of course, but also the fact that it hit after a year in which the country was torn in two over the future of its democracy. And, as Keret put it, the fact that “we were all there.” “In the morning, everybody turned on the TV,” he said. “And the TV had no information whatsoever. And no government officials came to the studio to explain. You didn’t know anything. “The only point of view you had was the point of view of people locked in the room, being burned alive, calling the television studio for help. Basically, all of Israel was locked in that room. “There’s something psychologically horrifying about it,” he added. “In such a small country, when more than 1,000 civilians die in one day, and more than 3,000 are wounded, and 200 are being kidnapped, and thousands survived by hiding under a pile of bodies. … “You have a really big chunk of people who their life either stopped or changed forever. Each of them is surrounded by a hundred people. His family, his friend, his partner, his parents. It’s as if the entire country is in post-traumatic disorder.” I’m supposed to write a conclusion now, or what we call in journalism a “kicker,” a last memorable thought to leave you with. I’m not supposed to let my interview subject have the last word because I’m a columnist; I’m supposed to have something to add. I’d rather leave it to Etgar this time. “When you’re scared and you’re holding something, and you can’t open your fist, you know?” he mused. “I think we should not look for our answers outward. We shouldn’t open our Facebook and say, ‘Who’s to blame? What’s going on?’ We should look from the inside. “This is what my parents taught me,” Keret said. “They gave me the lesson that when things are shaking, lean on yourself. Look for your center point. Nothing is going to save you. Because everything that used to be normal is not normal.” |

|

|

Thanks to Odeya Rosenband for contributing to this newsletter, and Adam Langer for editing it. Shabbat Shalom. Questions/feedback: [email protected] |

YOUR TURN: ISRAEL AT WAR LET US KNOW WHAT YOU THINK |

The last two weeks have been unlike anything else in my four years at the Forward. We have quickly mobilized to fully and fairly cover this horrifying, complicated story, to provide clarity amid the chaos that includes so much hate speech, misinformation and disinformation online. As of noon on Friday, we’d published 236 items about the war since the Hamas terror attack on Oct. 7. We have restructured our team and spent money we don’t have to provide on-the-ground dispatches. We have run opinion columns and personal essays from every perspective. I’ve spoken at eight community events in three cities and done half a dozen TV interviews. We’ve seen incredible engagement and thoughtful responses from you, our readers. Thank you. We are eager for more feedback — use the blue button below to send your questions, story ideas, sources, photographs or personal reflections. And if you appreciate what we’re doing, if you care about have a Jewish lens on the news that is independent, rooted in reporting and committed to the truth — please use the yellow button to make a donation. |

|

|

WATCH: PATINKIN & EINSTEIN |

Every Jewish communal conversation over the last two weeks has not quite been the conversation we’d planned. Mandy Patinkin was supposed to talk with me and our news director, Benyamin Cohen, about The Einstein Effect, Benyamin’s new book about the world’s favorite genius. That’s because the actor is also ambassador for the International Rescue Committee, a refugee group Einstein — himself a refugee — founded in 1933. We did talk about the book, about Einstein, about refugees — and about war and peace, and also about Patinkin’s wife’s ex-boyfriend’s burial plot in Maine. It was a wild ride, and a bit of a respite. |

|

|

(Original painting by Reuven Dattner) |

|

|

|