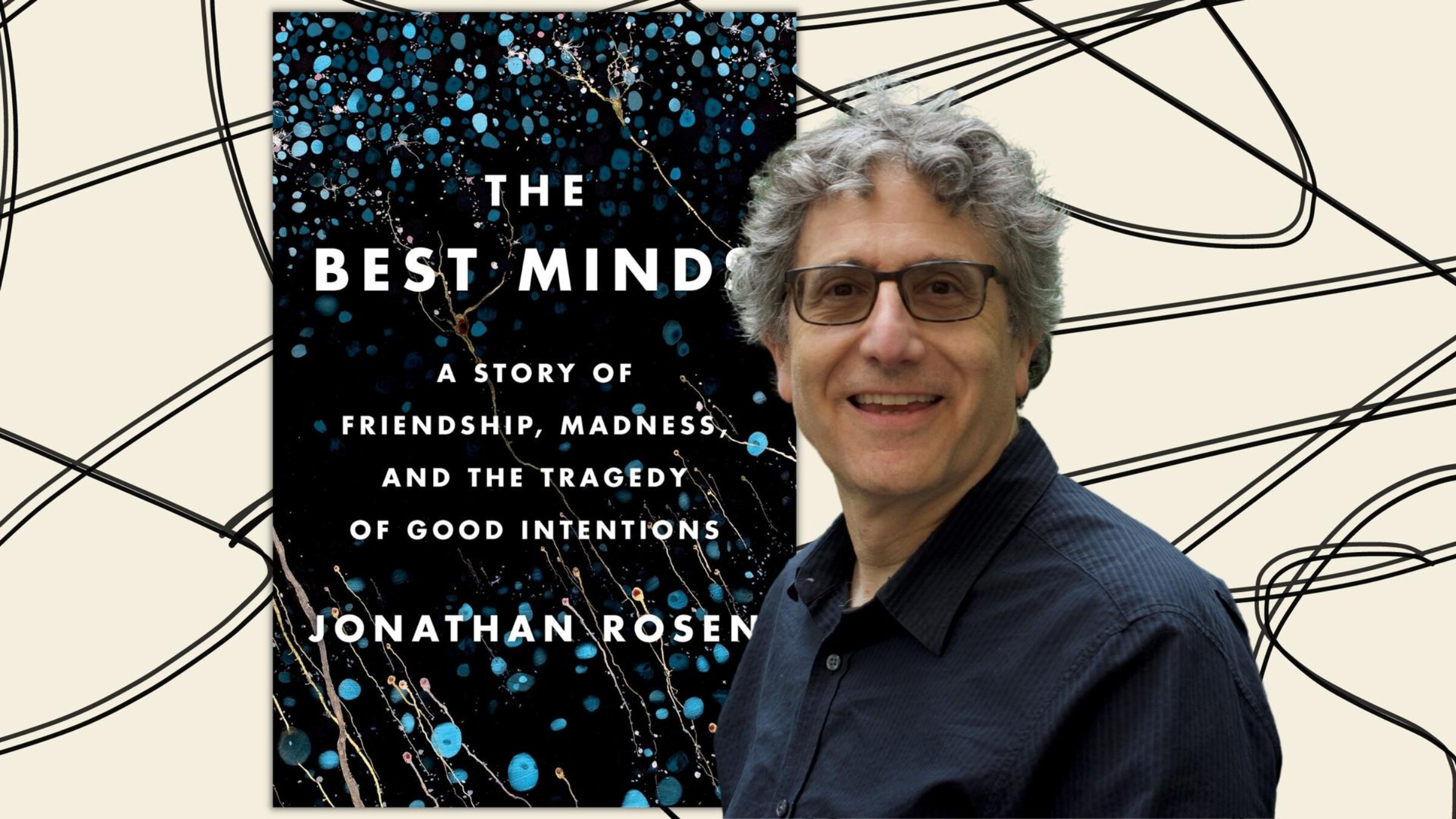

The Best Minds is a memoir and also much more. It is a deeply reported story about Rosen’s childhood best friend, Michael Laudor, who beat him at basketball and many other things before succumbing to schizophrenia and, somewhat famously, killing his pregnant fiancée. It is a meditation on mental illness and also something of a cultural, intellectual and legal history of deinstitutionalization.

Rosen, now 60, was the first culture editor of the Forward when the English edition started in 1990; created the Jewish Encounters Book Series and ran it until 2014; has served as a judge of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature; and just last night was talking about The Best Minds at a Jewish Book Council event. His other books include a novel called Eve’s Apple and a memoir of sorts called The Talmud and the Internet.

So his windy non-answer about what makes this book Jewish felt at once a bit heretical and deeply, essentially Jewish.

“When you have a baby and you’re holding your baby in your arms, you don’t feel the baby is incomplete for not being in a book,” he pointed out. “And you are perfectly happy if the name you give your child is a biblical name, and is part of a story that isn’t an original story you’re telling.”

Then he talked about his father, a professor of German literature who had escaped Nazi-controlled Vienna at age 6. “My dad was always saying ‘Choose life’ in a deeply complicated way,” Rosen said. “Because it really could just mean, ‘Don’t go to the prom with her because she’s not Jewish.’ But the largest sense is that it’s not a story. And that you don’t have control over the story.

“The horror of eugenics for Jews and everybody else who suffered because of it was that people thought they could control nature itself,” Rosen went on. “That what nature does brutally, and slowly, we can engineer. And a story is a little bit like that.

“Although I did write a story in a book, I kept realizing that I didn’t need to, and that I was never going to do justice to it.”

It took Rosen a decade to write The Best Minds, longer than any of his previous books. He said he resisted writing about Laudor’s 1998 murder of Carrie Costello and their unborn child for years, rejecting offers from The New York Times and other publications, refusing even to talk to reporters about the case.

The killing “had a very profound effect on me almost as if we were brothers,” he explained. “I didn’t know if I was protecting him or myself. Something terrible had happened. And I didn’t have a way of thinking about it in any, you know, detached, removed way.”

It was only when Rosen’s daughters, who are now 20 and 23, “reached the age I was when I met Michael,” he said, that that changed. He realized that the pain of what had happened, and his questions about it, “didn’t go away whether I stopped thinking about it or not.” So he went to visit Laudor in the psychiatric hospital upstate where he had been confined after the killing.

“Being a father changes a lot of things — I was old enough to be the father of kids who had met when they were 10,” Rosen explained. “She had a really good, close friend” that reminded him a bit of himself and Michael, he added, “and you realize her whole world is shaped by her friendship.”

The girls had not yet read The Best Minds when Rosen and I spoke a few weeks ago, but he said they “grew up with the story,” as he would sometimes stop to see Laudor en route to a family getaway to the Berkshires or the Hudson Valley.

“They both had very different reactions,“ Rosen recalled. “One daughter guessed right away that he had killed somebody. Why is he there? It looks like a prison. Well, it’s a hospital. But what’s the wall? Well, did he kill somebody? Yes. Was it somebody he knew? Yeah. Was it a woman? Yes.

“The other one was just like, well, isn’t anybody who kills somebody crazy? Nice to think so. Maybe. I don’t know.

“I think it will be very interesting for both of them to read it,” he added, because of how much the book reveals about himself. “I really did feel that I needed — in a way I hate, but there I did it, so I shouldn’t even say that — to stand as naked as anybody else in the book.”