Is it time to hit the panic button in our synagogues?

After FBI warns of ‘credible threat,’ 60% of preschoolers at my synagogue didn’t show up this morning

NYPD officers stand guard at the door of the Union Temple of Brooklyn on November 2, 2018. Photo by Getty Images

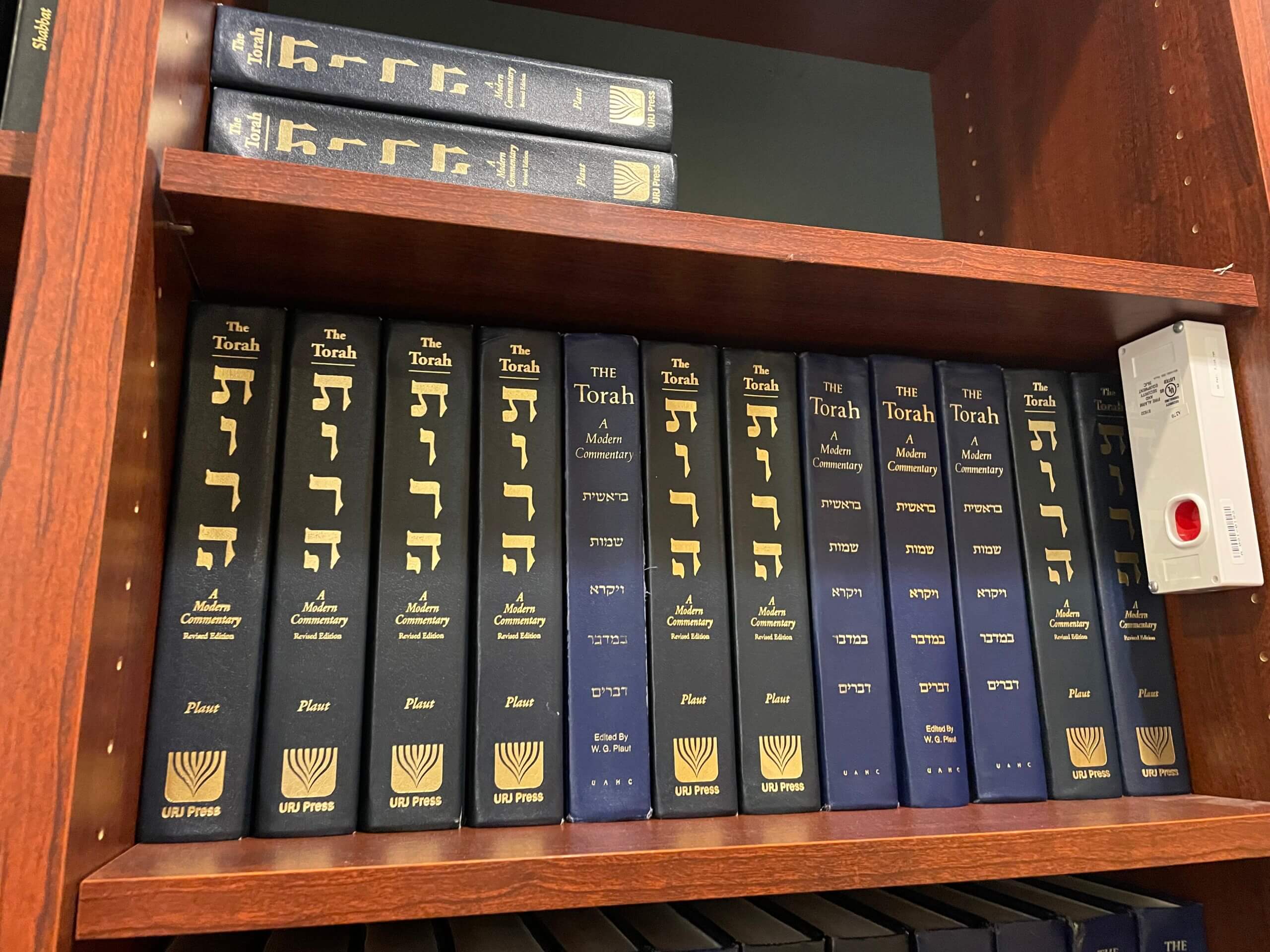

Here’s something I learned after the FBI warned yesterday of a “credible threat” to synagogues across New Jersey: My shul has a panic button inside the bookshelf at the entrance to the sanctuary.

There is also one by the ark where the Torahs are kept. And another in the rabbi’s office.

These little red buttons that silently dial 911 are among a host of security measures Temple Ner Tamid, a Reform congregation in Bloomfield, N.J., has added since 11 worshippers were shot dead during Shabbat services in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, 2018. Financed by a $100,000 grant from the Department of Homeland Security, they include boulders along the driveway to prevent car-ramming attacks; a film added on exterior windows that keeps them from shattering; 15 cameras; new lights; a key-card access system; an armed security guard on duty whenever the place is open for business — and signs saying the guard is armed.

“Part of the goal,” our rabbi, Marc Katz, explained when I spoke with him Thursday night, “is if someone is going to shoot up a synagogue, you don’t want them to shoot up your synagogue.”

Yes, friends, this is what it’s come to.

‘We’ve been preparing for this day for four years’

I was in a meeting when the FBI’s Newark office tweeted the broad and vague warning at 3:02 p.m. Wednesday urging people to “take all security precautions,” so I first heard of it, improbably, via the group-chat of the moms of my daughter’s religious-school posse. The prior text in the chain concerned carpool; the next was about buying Taylor Swift tickets.

Rabbi Katz also learned via text-message, from a congregant who works for our local congresswoman, and who had already been in touch with the Bloomfield police. When Katz turned to inform the synagogue’s executive director, Michelle W. Malkin, she already knew — because CNN had called asking for a response. Soon they both got emails, texts and robocalls from the local Federation’s security chief.

“But it was all 15 minutes after I’d heard,” Katz said, “and we were already working on it.” Two hours later, the synagogue president, Josh Katz, got an email from the Union of Reform Judaism’s emergency-response coordinator.None of these offered any more information about the nature of the threat, its specific target, or its origin. (The URJ’s email advised watching the FBI’s Twitter account.) And in some ways it didn’t matter. Those things probably would not have much affected what these individual synagogue leaders did in response. Which is actually not all that much, because they’d done so much — quietly, steadily — before.

“We’ve been preparing for this day for four years, since Pittsburgh,” Rabbi Katz explained. “My thought is mostly pastoral,” he added, “Michelle’s lane is mostly logistical, keeping people safe,”

A synagogue in action

So Malkin walked out to the playground and told the after-care coordinator to bring the 15 preschoolers inside. She called the Bloomfield police captain and asked how quickly he could send over a patrol car. The security company had already reached out to say they’d add hours for Thursday night and the weekend; the guard on duty did a perimeter check and locked the doors.

Meanwhile, Malkin and both Katzes were being bombarded with texts from concerned congregants. “The way you talk about it is pastoral, saying to people, ‘Don’t let them win, it’s OK in this climate to still be Jewish,'” the rabbi told me. “You don’t want to get injured by being Jewish, but you don’t want to be so scared that the threat stops you.”

Malkin penned a quick post for the temple’s Facebook group — “We are lucky to have new security upgrades, relationship with our local police, and attentive security personnel at this time!” A bit later came a pair of congregation-wide texts, the second one saying: “All temple programs will be happening as scheduled.”

Thursday evening, those programs included a “Stop the Bleed” training, where a member of our congregation who is an EMT taught temple board members how to apply tourniquets in case, you know, someone ever shot up our synagogue during services. “Hopefully you’ll get something out of it,” he said. “Hopefully you’ll never have to use it.”

As he spoke, an armed security guard sat in the lobby, and a Bloomfield police car was parked at the foot of the driveway.

The aftermath, with a lot of questions

This morning, an FBI official told a conference call of New Jersey synagogue leaders that the authorities had identified a single person as the source of the threat, approached him Thursday evening, and that “he is neutralized.”

That’s good, I guess. But only 40 of the 102 children enrolled at our synagogue’s preschool showed up for class on Friday. Which makes it hard not to feel like the terrorists are winning.

As I write this, there remain a lot of unanswered questions about this threat.

The FBI official said on the Friday morning call that the individual had expressed radical, extremist views and a desire to promote hate against the Jewish community. Was he a white-supremacist like the man who shot up the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh or an Islamic extremist like the man who took a rabbi and several congregants hostage in Colleyville — or was he motivated by some other twisted ideology? Did the vitriol spewed by Kanye West and Kyrie Irving or the Jew-hating hashtag campaign spawned by Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter help spur him on? Will he be prosecuted?

Was a tweet to FBI Newark’s 25,000 followers the right way to communicate this threat, not only to the public but to the people like Malkin and the Katzes who are actually responsible for protecting the synagogues? (The FBI official said on the Friday call that the tweet was “not intended to cause panic” but was the quickest way to warn people, given that schools were about to let out and evening services soon to start.)

And, most crucially and most elusively: what the heck are we supposed to do in the face of these threats, of rising antisemitism generally?

What to do during a ‘perfect storm’ of antisemitism

Malkin, for one, is applying for another Homeland Security grant: up to $150,000 is available now, and her list includes locks for the big swinging doors into the sanctuary and chapel; cages to protect the power supply; a perimeter fence; a security station in the parking lot where a guard could have eyes on both the playground and driveway; and more bollards to stop vehicles from driving into the building.

Josh Katz, the synagogue president, is again running through scenarios in his head. “You get everyone’s attention and you say, ‘What if, what if….’ What if someone just walks up the driveway with an AR-15,” he said. “Unfortunately with safety, you have to believe bad things can happen. Otherwise, you can’t prepare for them.”

And Rabbi Katz is rethinking what he’ll say at a forum he’d already scheduled for Sunday to help people process what he described in a Wednesday email as a “perfect storm” of antisemitism. “Am I more scared than I was yesterday? Yes. Am I scared to go into the synagogue? No, I am not,” Katz told me Thursday night as he ticked down the list of security upgrades, including those panic buttons in the sanctuary.

“It doesn’t mean I’m not going to be on edge this weekend,” he added. “But it means I can go into this weekend with integrity, knowing that we’ve done everything that we can.”

I wasn’t planning to go to Shabbat services tonight — I have tickets to a show at the high school — but I’m going to rejigger my schedule so I can swing by for a bit. Showing up at synagogue, it seems to me, is part of doing “everything that we can” to fight back against antisemitism, against terror.

Plus, now I know where that panic button is.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO