Love triangles and arias abound in this reconstructed 1911 Yiddish comic operetta

‘Shir Hashirim: The Song of Love’ returns to New York, where it premiered over a century ago, on Monday, Dec. 11

Courtesy of YIVO

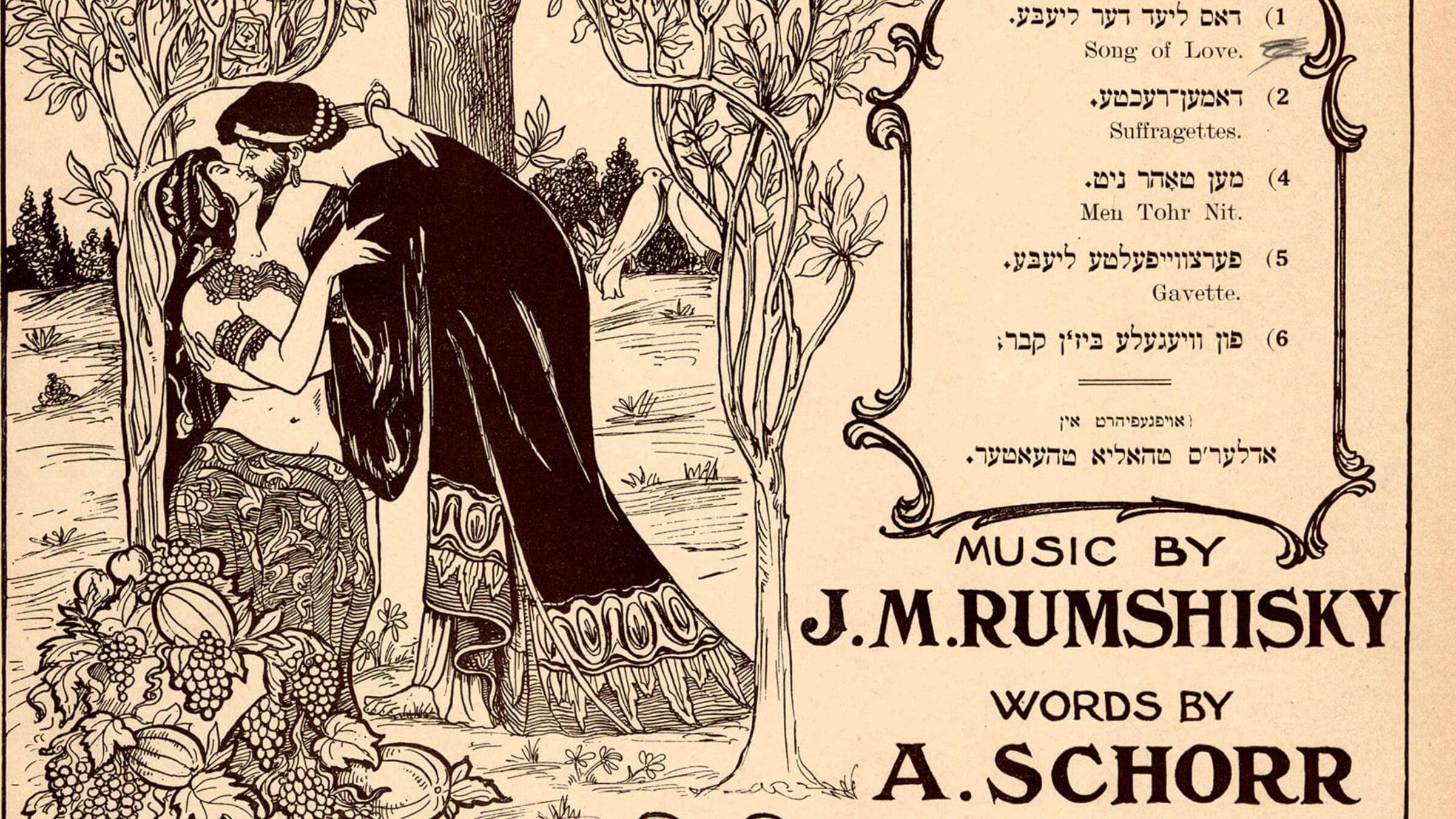

In 1911, the Yiddish operetta Shir Hashirim: The Song of Love premiered in New York City, and became immensely popular, performed on stages around the world for decades.

The musical comedy, composed by Joseph Rumshinsky and written by Anshel Shor, is about the love triangles of an aging composer along with his adult children and their lovers and friends. The composer, Leon Oppenheim, in the process of rehearsing his opera, Shir Hashirim — referring to the biblical text “Song of Songs” — falls in love with his family friend Lily against the will of his wife Anna.

Compiling manuscripts

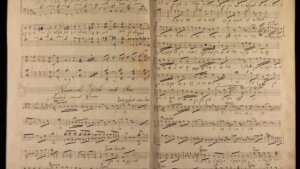

Though there are fairly complete manuscripts and recordings of the Shir Hashirim operetta, YIVO set out to reconstruct what would have been performed in the 1911 premiere. YIVO’s director of public programs and composer Alex Weiser, along with Yiddish theater scholars Max Friedman and Ronald Robboy, pieced together scores, many of them fragmented, scattered around the United States.

“We used sources both at YIVO, but also at UCLA and Library of Congress — we got stuff from wherever we could find it,” Weiser told the Forward. (Shir Hashirim is the oldest piece that Rumshinsky himself retained in his own archival materials, which are housed at UCLA.) The team consulted audio recordings — 78s of songs and a radio broadcast of the operetta from the 1940s.

Figuring out what passed for an approximation of the original was challenging. The team had to fill in fragments of missing words, and they couldn’t exclusively rely on later scores to reproduce the original for a litany of reasons: the tendency to mold the score to the performers at the time, the habit of adding whole parts and songs depending on the whims of whoever copied versions of it, the translation of Americanisms back into European Yiddish for versions performed in Europe, and the issue of musical scores not including all of their parts in full detail.

To Robboy, it was worth the effort. “Now that we have decoded and reconstructed music and lyrics, and understand their context, we can see why it was all so important,” he explained. “The work is, in a word, utterly engaging. And it points to how the Yiddish musical theater, along with the broader American musical theater it reciprocally influenced, would develop in the coming years.”

Comedic music shares the stage with serious arias

The songs within the operetta, set in upstate New York, reveal Rumshinsky and Shor’s range and ambitions; the operetta cobbles together topical comedy numbers with serious operatic arias, pushing the boundaries of Yiddish theater. The music sheds light on interesting transitions in American society, the Yiddish language and Rumshinsky’s own approach to his work, which can be seen in a sampling of the pieces.

The farcical “Damenrekhte,” or “Ladies’ Rights,” paints a comical picture of a world of female domination, which perhaps was not seen as impossible in a country that would give women the right to vote less than a decade after the piece debuted. Later in the operetta, the character Rosa complains (though humorously) about the hypocrisy of those who set limitations on women in the song “Men tor nit!” (“That’s Not Allowed!”)

“Hofenung Zise,” or “Sweet Hope,” contains subtle hints about a transition happening among Yiddish speakers at the time. During an opera rehearsal, Lily begins singing the Italian aria “Vorrei morire!” in Italian, but then switches to the Yiddish lyrics so “the older folks can understand it.”

However, this Yiddish is daytshmerish Yiddish — the Modern German-inflected Yiddish once used standardly in the Yiddish theater as well as other aspects of Yiddish society and culture that sought to distinguish itself as refined. “Akh, vi shmert zikh zint mayne leyden,” or “Ah, how painful are my sorrows,” could be almost directly transposed from German. The song serves as a means to mark a transition from the past, into a Yiddish that was performed closer to the way people would naturally speak, as the rest of the operetta is in non-daytshmerish Yiddish and uses American Englishisms throughout.

Rumshinsky also marked a personal transition in this operetta. He had long admired and studied both liturgical and classical music, and sought to elevate the craft of Yiddish operetta. The “Gavotte” that Lily sings is an operatic aria to the backdrop of an orchestra, in what would be considered a serious shift for the Yiddish theater.

You can listen to a 78 recording of “Gavotte” from YIVO’s collection:

How to sing in Yiddish

YIVO will host a performance co-sponsored by the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at UCLA of the songs accompanied by piano by students of the Bard College Conservatory Arts Program. The concert will take place Monday, Dec. 11, at 7 p.m. ET at the Center for Jewish History in New York, and will be livestreamed over Zoom.

Weiser said that YIVO worked extensively to prepare the singers for Yiddish pronunciation, which is often a challenge for musicians who are more used to German. They prepared an extensive guide for them, and sent scholar Lorin Sklamberg and Robboy to Massachusetts to coach the students.

The hope is that this performance, limited to the songs and the piano, could expand in the future to a fuller showing with an orchestra, choir and the full script.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO