I grew up Jewish on a chicken farm. This book gets it right.

The surprising story of Holocaust survivors in rural New Jersey

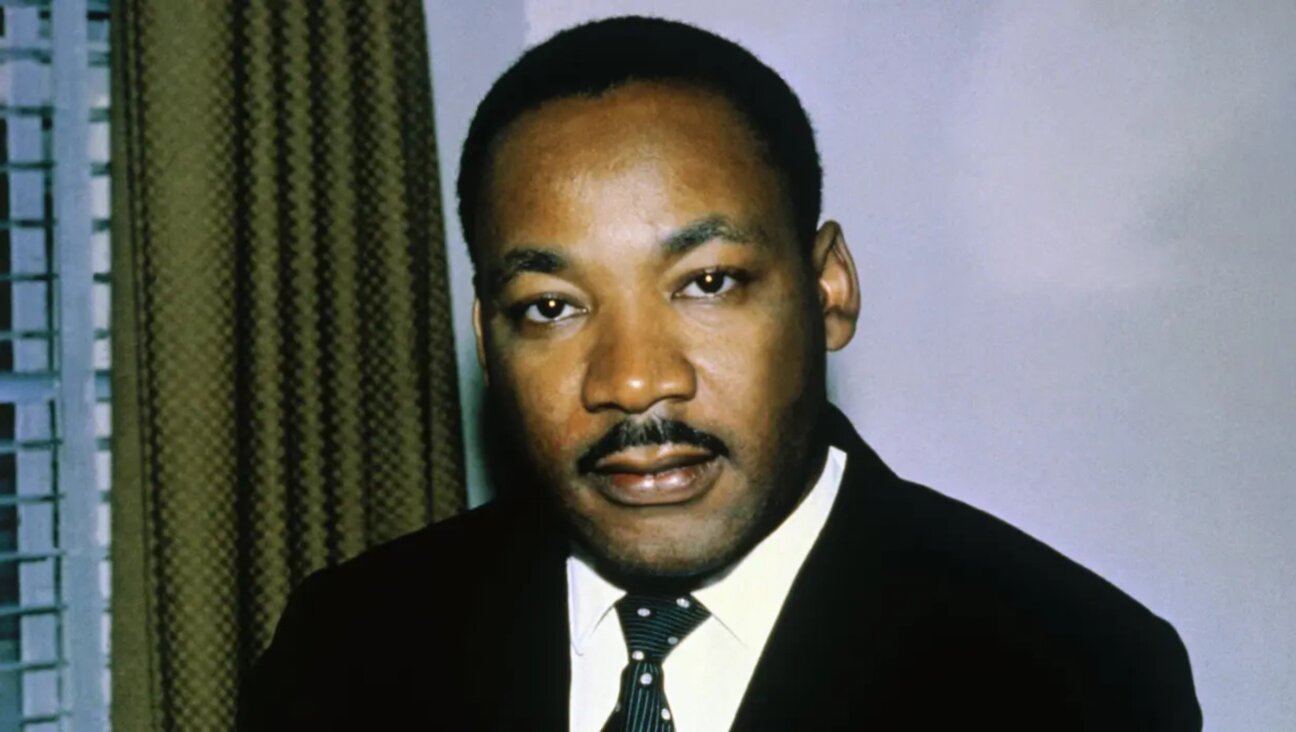

Family-owned poultry farm in Vineland, New Jersey in the 1950s Photo by Max Salier

If only I had a dollar for every time I heard that growing up Jewish on a chicken farm in southern New Jersey was somehow an inauthentic Jewish experience. I’d be sipping a mai tai poolside in Miami by now.

Instead, here I am in the Bronx writing about Holocaust survivors whose south Jersey community of chicken farmers had its moment — and then failed.

No complaints, especially because I have Seth Stern’s excellent social history to buttress my argument that a significant number of Holocaust survivors, most of them Polish and Ukrainian Jews, settled in Vineland and other southern New Jersey towns to create an American facsimile of their lost eastern European shtetlekh.

In Speaking Yiddish to Chickens: Holocaust Survivors on South Jersey Poultry Farms, Stern not only pinpoints the economic hardships and social dislocation the survivors experienced. He also writes that survivors on Cumberland County’s chicken farms typically lived lives richer in traditional religious observance than most New York suburbanites, whose Jewish identity often began with Saturday night poker games and ended with Sunday morning bagels and lox.

Stern joins a flank of third-generation, or so-called “3-G,” writers committed to exploring the impact of the Holocaust on their grandparents. It’s a testament to the affection Stern felt for his grandmother Bronia that he began peppering her with questions about the chicken farm phase of her life two decades ago when he was in his 20s.

A robust Jewish immigrant community

One-on-one interviews were a good start, but Stern, now a legal journalist and editor at Bloomberg Industry Group, wanted to document every aspect of the Vineland Jewish community of the 1950s and 1960s. The details he unearthed track with my own memories of my Holocaust survivor parents who vaccinated thousands of chickens against Newcastle Disease, rebuilt coops destroyed during Hurricane Hazel, ditched business partners and hired hands, and watched Texaco Star Theatre Starring Milton Berle on their cutting-edge black-and-white TV set.

Stern’s archival research at the Jewish Agricultural Society, the Jewish Federation of Cumberland County, the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive and various university libraries yields a picture of a robust rural Jewish immigrant community in an era when most American Jews were leaving big cities for the suburbs. Chicken farming, however, was not without risk. The opportunity for an independent country life hinged on access to capital and ever-fluctuating egg prices. As Stern learned:

“Poultry farmers … could do everything right and yet their fate rested largely with forces beyond their control. Faraway commodities exchanges determined egg prices, which farmers listened for on the radio or checked six afternoons a week in the [Vineland] Times Journal.

“As in all branches of animal husbandry, so much depended on their hens’ health. Even in good years, the Grine [immigrants] felt as if chickens conspired against them, getting sick and laying fewer eggs as soon as prices rose. One survivor farmer in Vineland later summed up the dilemma this way: ‘When you got the eggs, there’s no [good] price and when you got the [good] price, there’s no eggs.”

My sister-in-law, who grew up in Vineland — and who happened to be reading Speaking Yiddish to Chickens at the same time as me — told me her father, a Vineland chicken farmer desperate to make money, once went door-to-door selling eggs. At the end of Day 1, his profit totaled $1.50. He never tried door-to-door egg sales again.

Pushed off the land by economic fate

By 1962, the vicissitudes of the egg business resulted in hundreds of impoverished farmers. Some moved to New York and took factory jobs. Some stayed close to Vineland and worked full-time at the Crown Clothing Company factory. The more enterprising grine, or “greenhorn” immigrants, segued into entirely different businesses, such as oil distribution, real estate development and a “sewing machine empire.”

Stern’s grandparents finally threw in the towel in July 1964 and left Vineland for East Flatbush in Brooklyn. Their arrival coincided with the New York race riots, protests in Harlem and Brooklyn against police brutality. When Stern asked his mother how her parents felt about the city’s upheaval, she said, “I don’t think they knew. I don’t think they cared.” They were just relieved to leave the chicken business behind.

Life wasn’t a lot easier in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, where the author’s grandfather Nuchim opened a convenience store, which failed, and then a children’s clothing store, which failed too. “He had lousy luck, no luck,” Stern’s mother concluded.

The beauty of Speaking Yiddish to Chickens lies in Stern’s skill at conveying the ups and downs of some 1,000 survivors, each with their unique hardscrabble story. Despite the view of Jews today by some people as unfairly privileged whites, the children and grandchildren of south Jersey chicken farmers know their recent ancestors “hobn zikh gemitshet,” or struggled along, for decades after the Holocaust, with dashed hopes and wounds that never truly healed.

As for those people who thought my childhood on a south Jersey chicken farm not quite Jewish, I can only share a memory of my father, pulling off the high rubber boots he wore in the coops and slaughterhouse, and hurrying into our kitchen to daven mincha. He never did find time for Saturday night poker.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO