Leonard Cohen once denounced Yiddish. Why did he perform this Yiddish folk song?

It may have been a way to work out his Holocaust trauma.

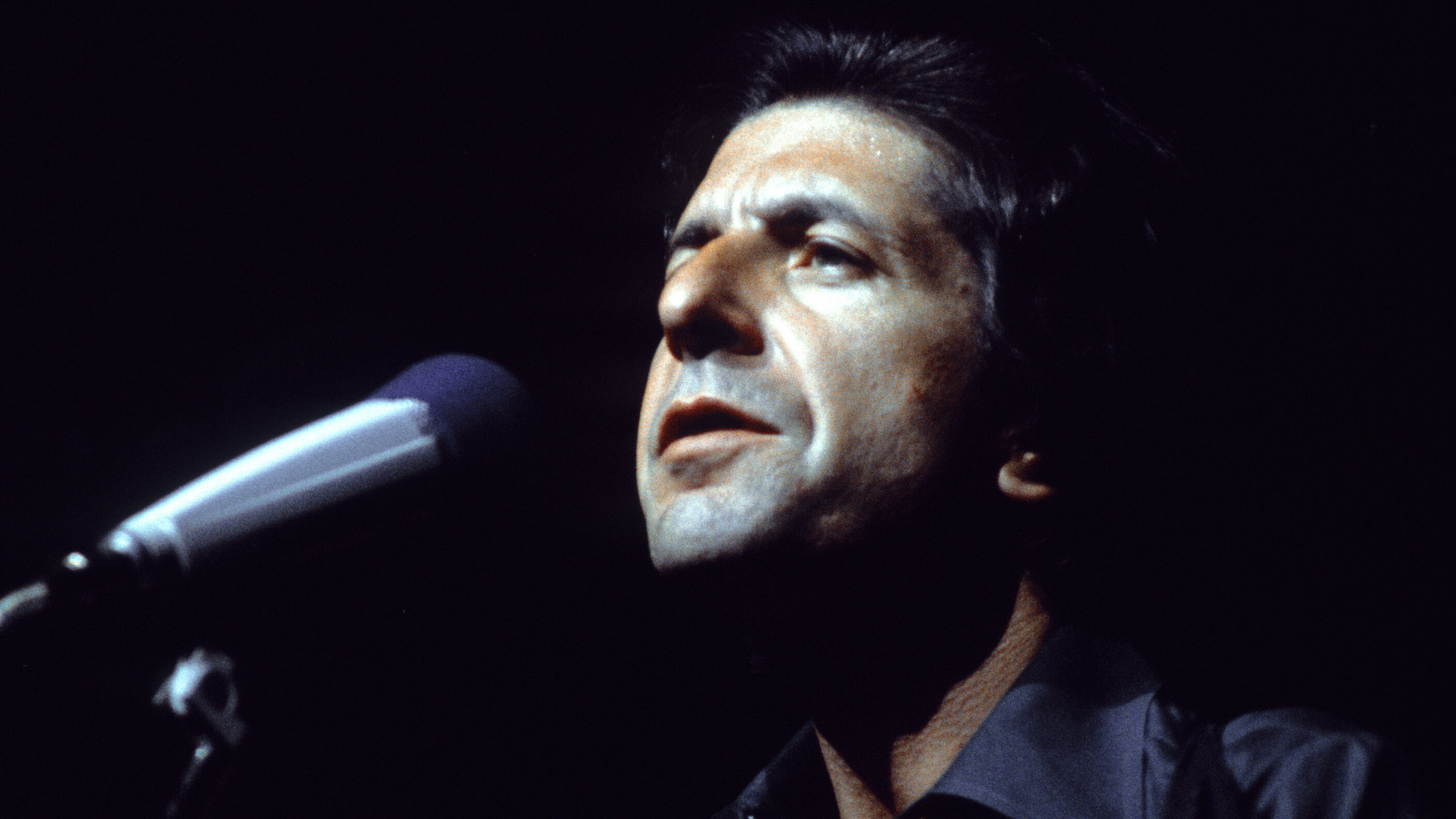

Leonard Cohen performs on stage in London circa 1975. Photo by Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

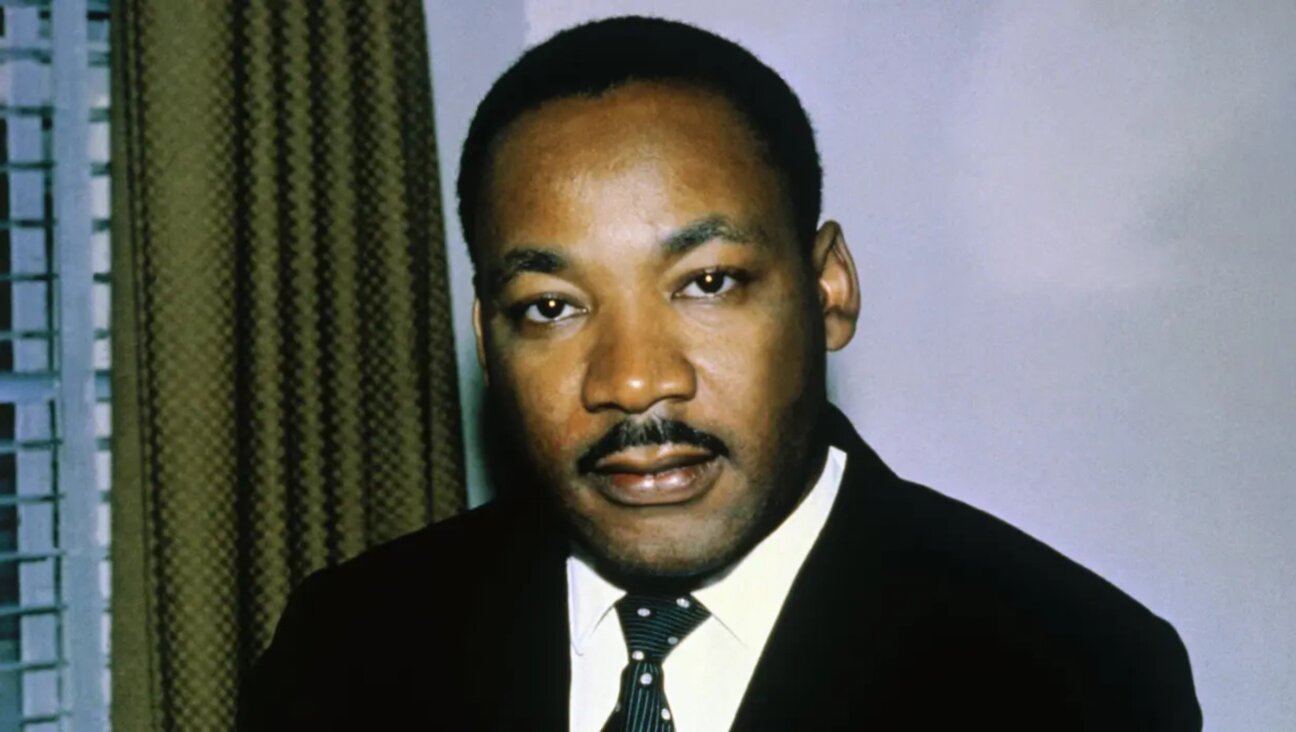

Leonard Cohen’s rich legacy of poetry, fiction and songs is the subject of many articles and essays, analyzing his complex ideas and life. But many remain unaware of the Canadian songwriter’s performances of a Yiddish folk song.

In 1976, Cohen embarked on a European tour that took him to Vienna, playing in a cultural center that local artists were trying to save from being torn down by the municipal government. At the end of his set, he began singing the Yiddish folk song “Az der rebe zingt” (When the Rebbe sings), first made famous by the legendary Jewish folk singer Theodore Bikel.

The song pokes fun at the extreme devotion of Hasidim to their Rebbe, imitating everything he does. “When the rebbe sings, all the Hasidim sing. When the rebbe dances, all the Hasidim dance. When the rebbe sleeps, all the Hasidim sleep.” It was probably invented by Maskilim — Jewish modernizers of the 19th century who fought against what they saw as backward religiosity.

Bikel’s 1959 version retains its satirical tone, but later versions, including Cohen’s, no longer have the sense of irony heard in Bikel’s rendition, and seem instead to celebrate that Hasidic devotion. Instead of mindlessly imitating their rebbe, Hasidim follow him consciously to express their spiritual faith. Folklore scholar Itzik Gottesman learned from a source in the Hasidic enclave in Jerusalem, Mea Shearim, that you can, on occasion, hear this song sung by children in kheyder.

Cohen performs the folk song slowly and soulfully as though he himself is entering a trance. (He also uses the Israeli Hebrew pronunciation for the word “hasidim,” but that may not have been deliberate.)

‘The language of my spirit is English’

But Cohen didn’t always have a positive view of Yiddish.

Almost a decade before, Cohen publicly denounced the language. He did this as a panelist at a 1967 symposium of Canadian Jewish writers in Montreal, which also featured the late Yiddish poet and essayist Melech Ravitch and the future Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse. The symposium was recorded on audio by Montreal’s Jewish Public Library, and can be found on the Yiddish Book Center’s website.

Ravitch said that familiarity in Jewish languages like Yiddish and Hebrew was essential for a Jewish writer, so that they would not “submerge into the waters” of another society.

“The language of my spirit is English,” Cohen, then 32 years old, retorted. “Mr. Ravitch manifests an interesting nostalgia for Yiddish and Hebrew, but if he believes that the future of Jewish emotion and spirituality resides in those two languages, he must relegate the entire North American Jewish experience to the outer limits.”

He went further in his critique of the Yiddish writer, saying that a focus on language itself was a barrier for the spiritual encounter that he saw as the essence of being a Jew.

Cohen offered a different approach to religion, a prescription that he himself followed up on. “Let us encourage young men to go into the deserts of their heart and burn the praise of perfection. Let us do it with drugs, or whips, or sex, or blasphemy, or fasting, but let men begin to feel the perfection of the universe.”

Panelist Adele Wiseman objected. “I would like to protest against, although I understand what you’re getting at, the romanticization of people like junkies. If you’ve ever had much to do with them, they haven’t had a quarter’s fingernail of experience in the spiritual realm.”

Cohen sarcastically pushed back: “I do not suggest that everyone shoot themselves with junk — you don’t have the veins for it, most of you.”

Nervous laughter filled the room. “I must confess in my wildest dreams, I didn’t imagine that this would be on the program tonight,” remarked moderator Neil Compton.

But despite Cohen’s expressed need for universalistic prophetic experiences outside of the normal Jewish synagogue life, he also made a defense of the particularities of the Jewish experience at the symposium. “The Jew has a particular kind of vocation. It was his blood that apprehended a particular kind of divinity. It is that kind of apprehension that keeps the people alive. Without the exercise of that apprehension he becomes nothing but a mere consumer of the world’s goods.”

He frequently used Jewish ideas and references from Hebrew scripture and prayer.

When Cohen transitioned from being a poet and fiction writer to singer-songwriter, he began composing songs with Jewish allusions, but always to prayers he may have heard in his synagogue Shaar Hashomayim, or stories in the Bible. “Who By Fire” is adapted from “Unetaneh Tokef,” the central liturgical poem of the High Holidays, and “Lover Lover Lover” references the patriarch Jacob; both were inspired by Cohen’s visit to Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. “Hallelujah,” released in 1984, recounts the story of King David and Bathsheba.

But given the antipathy Cohen expressed for Yiddish, what explains the direction that he took to express his Jewish identity through Yiddish? The musician’s own words at that 1967 symposium was suggestive of where this came from.

The Jew as a mirror in the world

In Cohen’s analysis, not only are Jews supposed to turn to God, they also act as mirrors to the non-Jewish world. “The glory of the Jew: that he is despised, that he moves in this mirrored exile, covered in mirrors, and as he passes through the communities that he sojourns, he reflects their condition, his condition.” For Cohen, that meant expressing the ugliness of Nazism and the pain of the Holocaust (which in 1967 was still painfully raw in people’s memory) before the audiences in Central Europe.

In 1970, he infamously gave the Sieg Heil Nazi salute to a crowd in Hamburg. Six years later, at the concert in Vienna, he chose a different way to express his anger. He chose to sing a song in Yiddish with the intention of praising the mysticism of the Hasidim, who together with most Jews in Eastern Europe, were annihilated by the Germans. It was a decision of a more mature Cohen.

His motivation to serve as that mirror came from somewhere.

Aubrey Glazer, a rabbi and author of Tangle of Matter & Ghost: Leonard Cohen’s Post-Secular Songbook of Mysticism(s) Jewish & Beyond” suggested to the Forverts that there was a great deal of Holocaust-related trauma that Cohen was working through. “Montreal was a hub for Yiddish-speaking survivors,” Glazer explained, saying that being around people with such raw feelings seeped into Cohen’s subconsciousness.

Cohen confronted his feelings with a language that he had once dismissed, using a song that he transformed into an experience of Hasidic prayer from a world that had seemingly been wiped away. He returned to “Az der rebe zingt” in 2013, singing it in the same style that he performed in in 1976. Ravich may have been right: A Jewish poet like Cohen could not stay grounded in his Jewish identity without Yiddish and Hebrew.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO