Why you never heard of the avant-garde Jewish artist Sarah Shor

She survived pogroms, Stalin and more — by safely avoiding the spotlight

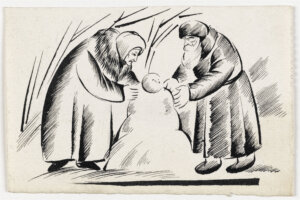

Sarah Shor, “Untitled” Photo by Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme, Paris (mahJ)

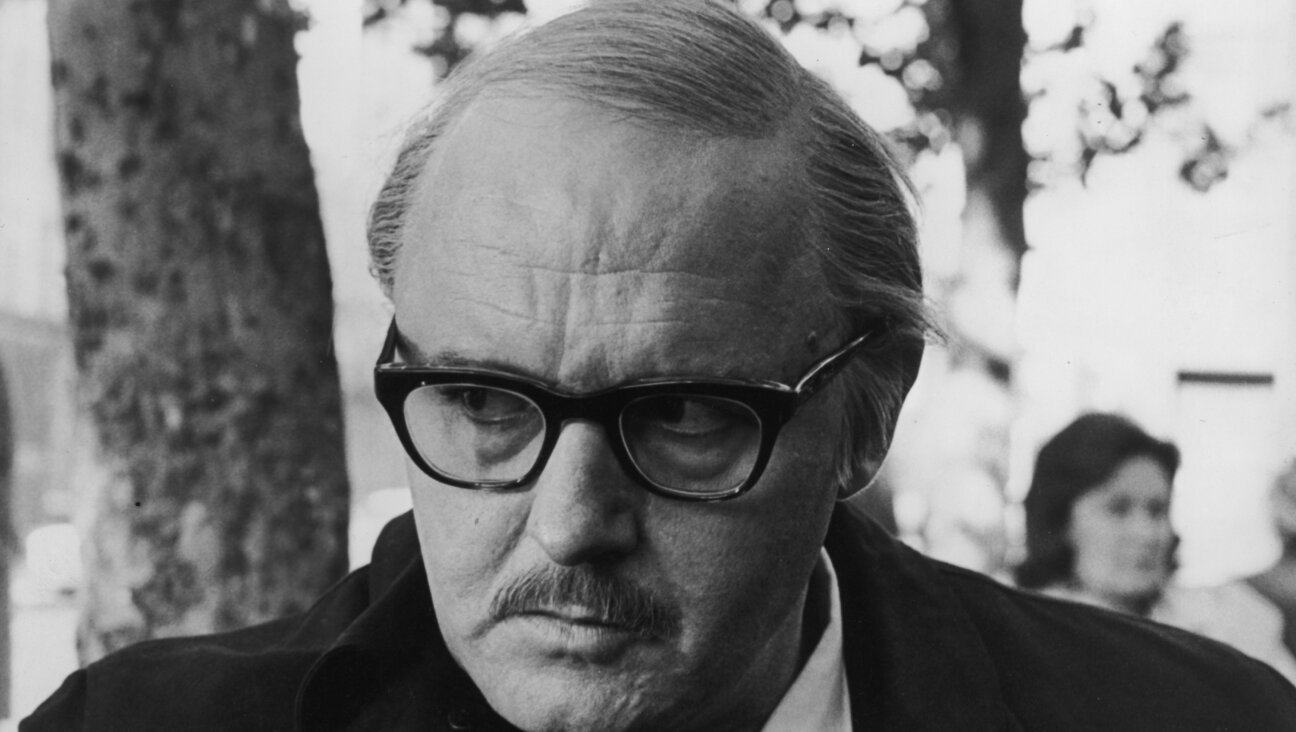

Like many talented Jewish artists at the turn of the 20th century, Sarah Shor (1897-1981) is hardly known to the general public today. She belonged to the most avant-garde circles in her native Ukraine, and was well-respected by both Jewish and non-Jewish painters and graphic designers. She made a particular mark illustrating Yiddish books with a fusion of cutting-edge radicalism and whimsical charm. Like some of her most important Jewish contemporaries — such as Issachar Ber Ryback and the young El Lissitzky — she deeply sympathized with the quest to create a “Jewish national art” — so Jewish themes were prominent in her work throughout her long career.

Sarah Shor was born into a mercantile family in Dubno, Ukraine, on March 30, 1897. By 1911, at the age of only 14, she was attending painting classes at the Kiev School of Fine Arts, where she became friendly with Ryback and other rising young Jewish artists. At age 17 in 1914, she was invited to participate in an exhibition in Kiev titled “Kiltse” (“The Ring”), organized by the prominent non-Jewish painters Alexandra Exter and Alexander Bogomazov. She then attended the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts before returning to her family, who had relocated to Khodorkov.

In 1919, the family experienced a horrible pogrom in Khodorkov. Witnessing antisemitic brutality with her own eyes deeply affected Shor’s sense of her Jewish identity and deepened her commitment to include Jewish subject matter in her art.

Shor returned to Kiev in 1919 and began the most formative period of her career. Her style was strongly influenced by the emergence of Cubo-Futurism in Ukraine: a dynamic amalgamation of the “shattered” forms of French Analytical Cubism and the fascination with movement and mechanization of Italian Futurism. Most importantly, she became associated in Kiev with the Kultur-Lige (League for Culture), the short-lived but vibrant movement intended to fuse the cultural innovations of 20th-century Europe with the authenticity of the Jewish experience in Eastern Europe. The Kultur-Lige was founded in Kiev in 1918 by Jewish socialist writers, artists, actors, musicians, educators and publishers.

One of its members, A. Litvak, authored a “manifesto” in Warsaw in 1921, summing up the group’s philosophy and achievements. Their mission was to reach the “broad Jewish masses,” both to bring them awareness of the new European culture and to draw upon the finest and most beautiful aspects of traditional Jewish life: “the accumulated nectar of generations,” as the manifesto eloquently put it. The Kultur-Lige was thus a kind of conduit both to and from the world of the Jewish shtetl, which would “transplant … the new culture into an old soil, creating a union of our history, which lives in us, with the culture of the new age.”

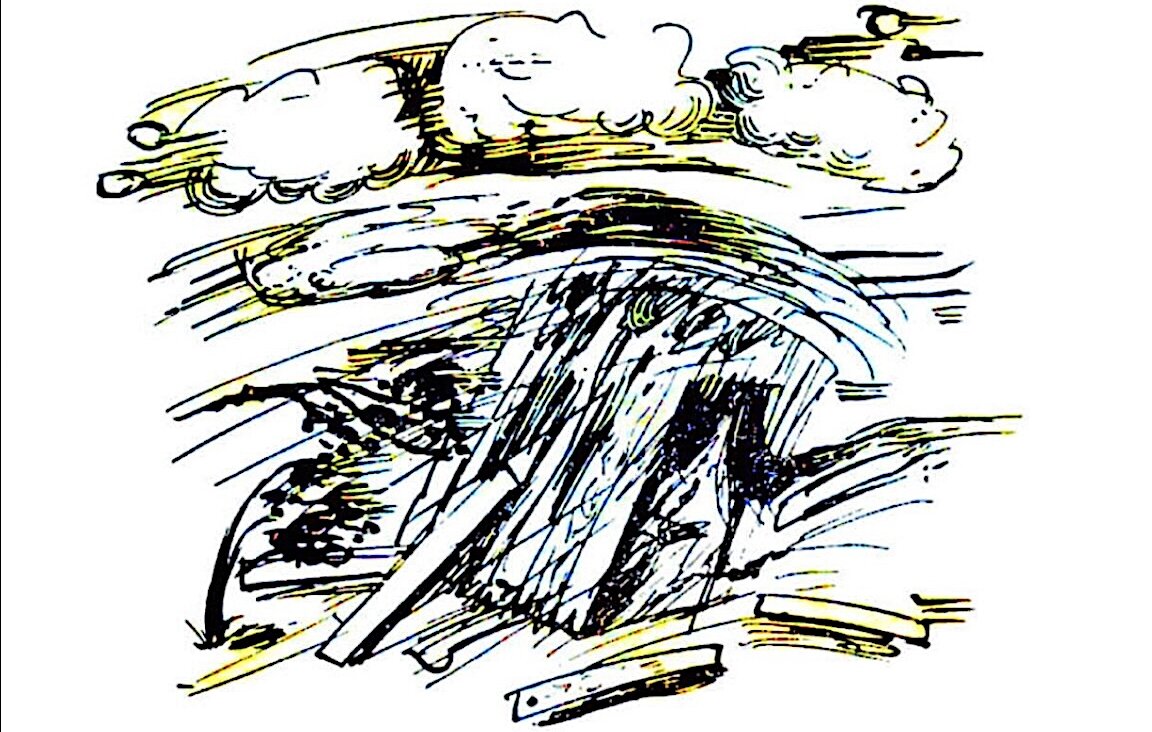

The Kultur-Lige was divided into sections according to specialty (art, music, literature, education, publishing etc.). While Shor never officially joined the art section, she worked closely with various members and shared their aesthetic and philosophical goals. During this period, she created designs in a striking Cubo-Futurist style for a never-produced version of Abraham Goldfaden’s play “Bar Kochba,” planned by the Kultur-Lige’s own theater studio. She also designed sets for a variety of avant-garde Ukrainan and Russian theaters.

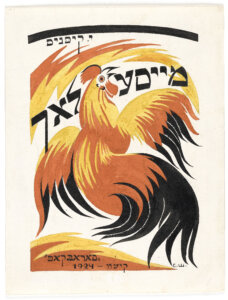

At about the same time Shor became seriously interested in book illustration. She shared this commitment with other members and affiliates of the Kultur-Lige, including Ryback, Lissitzky, Iosif Chaikov and Marc Chagall. Because literacy in Yiddish was high among Jews in the Russian Empire, iIllustrated works of modern Yiddish literature were the perfect vehicle for disseminating the new Jewish “national” culture. Children’s books were a particular focus, aimed at receptive young readers who would carry the Jewish cultural mission into the future. The Kultur-Lige founded its own press in Kiev in 1920, producing some of the most beautiful and innovative Yiddish books ever created.

Shor worked with a variety of presses producing Yiddish books — including the Sorabkop in Kiev — and also in Russian (particularly Academia Publishing House in St. Petersburg, which hired her as part of its permanent staff in 1932). Some of her most delightful illustrations were produced for children’s books written by the important Yiddish author, Itzik Kipnis. She designed covers for several collections of his stories, such as “A Ber iz Gefloygn” (“A Bear Flew,” meaning “tall tales,” Kultur-Lige, 1924); “Rusishe Mayselekh” (“Russian Stories,” Sorabkop, 1924); and “Mayselekh” (“Stories,” Sorabkop, 1924). The boldly angular and energetic style of these covers is completely consistent with Cubo-Futurist innovations, and extends to the Yiddish fonts that march confidently across the designs. The colors are vivid and eye-catching to attract child readers. The striking illustrations inside the books similarly combine the sharp angles, geometric shapes and strong black-and-white contrasts of cutting-edge European graphic art with great charm and narrative flair: whether depicting a traditional Jewish family walking in a shtetl street (with a bear ambling behind them!); barnyard animals charging at a peasant family; a cat and a fox making music together, or an elderly couple building a snowman.

Sadly, Shor’s later career was marred by the Stalinist crackdown on “cosmopolitans” — primarily meaning creative Jews whose work was perceived as too sympathetic to Western values. She did have a solo exhibition in Moscow in 1945, the only one of her career. But by 1948, the climate for Jews in the Soviet Union had become ominous. Several writers and artists who were her personal friends — including former members of the Kultur-Lige (some of whom had later become active in the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee) — were arrested, tortured and murdered. Her survival came to depend on keeping a low profile, and she was no longer able to work publicly as an artist. Instead she supported herself by designing educational materials for schools. She continued to paint and create graphic works privately, often with Jewish themes, until her death in Moscow on Oct. 10, 1981.

Sarah Shor’s life, and the artistic and cultural world to which she belonged, deserve to be better known. Readers can explore her works further on the website of the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme: https://mahj.org/en/collections-online/search?collection_fulltext=sarah+shor

Ellen Kellman contributed to this article.

Correction: The original version of this article misspelled Lissitzky.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask you to support the Forward’s award-winning journalism during our High Holiday Monthly Donor Drive.

If you’ve turned to the Forward in the past 12 months to better understand the world around you, we hope you will support us with a gift now. Your support has a direct impact, giving us the resources we need to report from Israel and around the U.S., across college campuses, and wherever there is news of importance to American Jews.

Make a monthly or one-time gift and support Jewish journalism throughout 5785. The first six months of your monthly gift will be matched for twice the investment in independent Jewish journalism.

— Rukhl Schaechter, Yiddish Editor