How the Soviet Jew was made

In his novel, “Judgment,” Dovid Bergelson describes how the pogroms convinced Jews to support the Soviet authorities.

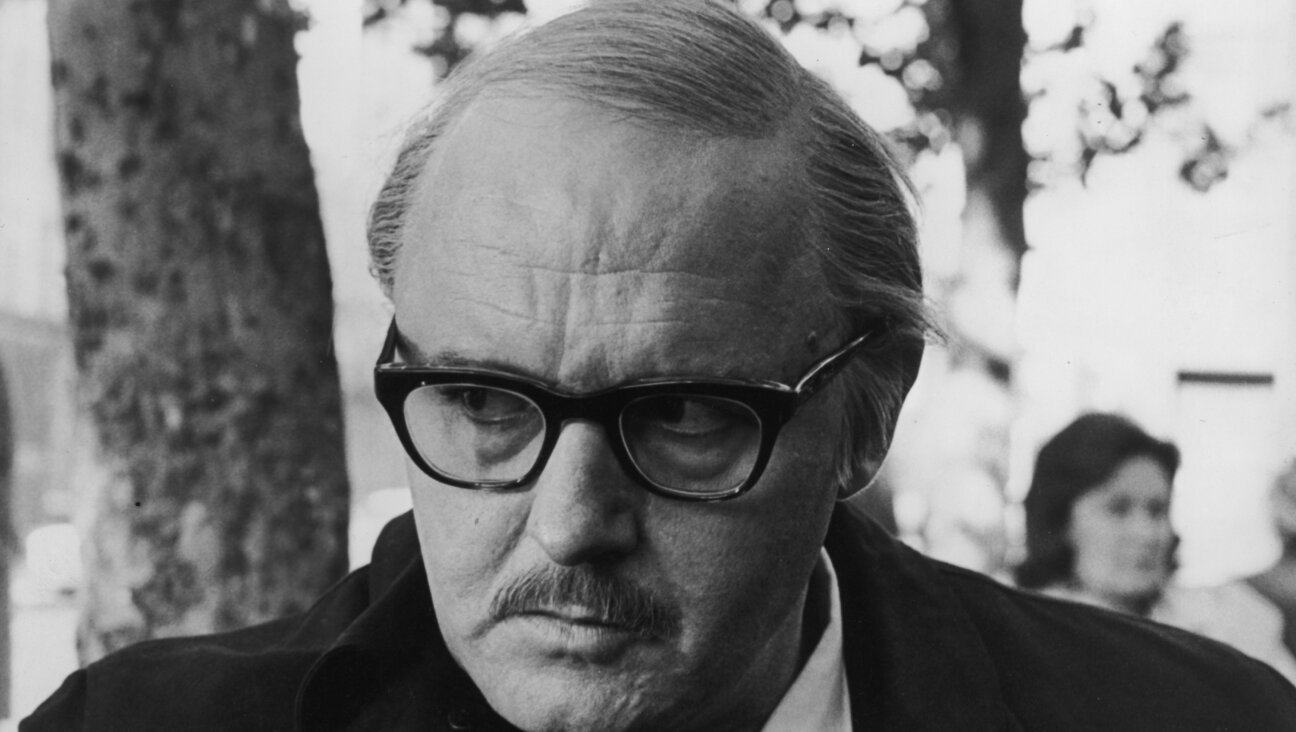

Courtesy of Sasha Senderovich

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Russian nationalists have been claiming that the Jews had hijacked Russian literature.

A number of Soviet Russian writers, especially in the years between the October Revolution and World War II, were indeed of Jewish descent. Most of them had scant interest in the Jews or their concerns, and often used Russian or Ukrainian pen names in order to hide their Jewish identity. However, some writers did write on Jewish issues, among them — Isaac Babel, Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg.

Scholars of Russian literature frequently debate whether there ever was a unique Russian-Jewish literature, or whether works by Jewish writers in Russian might best be seen as a part of Russian literature. But only a handful of researchers, like Prof. Sasha Senderovich, are knowledgeable enough in the field of Soviet-Jewish literature in Yiddish to make a comparative analysis between fiction written in Russian and in Yiddish. One result of this research is his new book, “How the Soviet Jew was Made.”

Senderovich traces the paths of literary figures who left the Tzarist-era Pale of Settlement to seek their fortunes in the ample fields of the Soviet lands, all the way up to the far ends of Siberia, by the Chinese border. His guides are the classical writers of Soviet-Russian and Yiddish literature: Dovid Bergelson, Moyshe Kulbak, Isaac Babel, as well as lesser-known authors like Viktor Fink and Semen Gecht. A whole chapter deals with Soviet films on Jewish themes, like “The Return of Nathan Becker”. The movie’s protagonist is a Jew, who in his younger days emigrated to America and then decided, years later, to return to the Soviet Union to help build socialism. Peretz Markish wrote the screenplay for this film which was then produced in two versions, one in Russian and the other in Yiddish.

In his introduction, Senderovich explains that the concept of Soviet Jewry actually was first conceived in the West, during the Cold War. In the first years of the Soviet regime, he claims that Jews were not yet completely “Sovietized” in their lifestyle and worldview. They tried to adapt to the new conditions but also maintained, at least in part, their Jewish identity. This kind of “transitioner” was depicted often in the Jewish literature of that era. These characters were Janus-faced: one face looking towards the Soviet future and the other turned towards the past. This ambivalence is the main theme of Senderovich’s research.

Bergelson’s “Judgment” and Kulbak’s “The Zelmenyaners” are two of the most important Yiddish novels that deal with the making of the new Soviet Jew. In “Judgment” and other fictional works from the 1920s, Bergelson artistically depicts the traumatic consequences of the pogroms from the civil war in Ukraine. These bloody events convinced many Jews to support the Soviets. They believed that only the Red Army had the power to protect them from bloodshed.

The relationship between Jews and the new Bolshevik authorities was not exactly smooth, though. The Soviets prohibited the private business of traders and artisans, which had been the economic basis of the shtetl. In the 1920’s, the Jews left the impoverished shtetls en masse and settled in big Soviet cities. This caused a rift between the old generation which held onto the old way of life, and their children, who wanted to fit into the new Soviet society. This conflict is the theme of Kulbak’s satirical novel, “The Zelmenyaners.”

The plan to create a Soviet-Jewish Autonomous Region in Birobidzhan next to the Chinese border was the most radical Soviet project to “productivize” shtetl Jews. The project was a failure, but a number of Jews traveled to the Far East to build a new settlement. Gekht’s novel “The Steamship Goes to Jaffo and Back” is about a Jew from Odesa who settles in Palestine but becomes disillusioned by the Zionist dream and returns to Birobidzhan. Gekht’s depiction of the Zionist Yishuv in the 1920s is critical but full of authentic details, despite the fact that he had never been there himself. Birobidzhan, on the other hand, gets portrayed as a sweet dream which had already been realized — in accordance with the dictates of Soviet socialist realism.

The most striking embodiment of the Jewish duality is the figure of a swindler, which we find in Ilya Ilf’s and Yevgeny Petrov’s novels “The Twelve Chairs” and “The Little Golden Calf.” Their hero, the Great Schemer – Ostap Bender, was one of the most popular literary figures in Soviet literature. He’s a perpetual wanderer, traveling around the Soviet Union looking for victims for his con games. His goal is to get rich and settle in Rio de Janeiro, but his dream goes up in smoke when he’s robbed by Romanian border guards.

The Holocaust and the persecution against Jewish culture at the end of the 1940’s caused a deep and traumatic split in Russian-Jewish history. These bitter experiences tragically altered the Jewish cultural legacy of those first Soviet years, Senderovich writes. He believes that people today read the important literary works of the 1920’s and 30’s as a preview of the tragic 1940’s. What this book aims to do is demonstrate how Soviet Jewish writers created lively new Jewish heroes during the years between those two bloody catastrophes, the civil war and the Holocaust.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask you to support the Forward’s award-winning journalism during our High Holiday Monthly Donor Drive.

If you’ve turned to the Forward in the past 12 months to better understand the world around you, we hope you will support us with a gift now. Your support has a direct impact, giving us the resources we need to report from Israel and around the U.S., across college campuses, and wherever there is news of importance to American Jews.

Make a monthly or one-time gift and support Jewish journalism throughout 5785. The first six months of your monthly gift will be matched for twice the investment in independent Jewish journalism.

— Rukhl Schaechter, Yiddish Editor