“In the Wild Forest” – A Yiddish Song from Romania, Revived

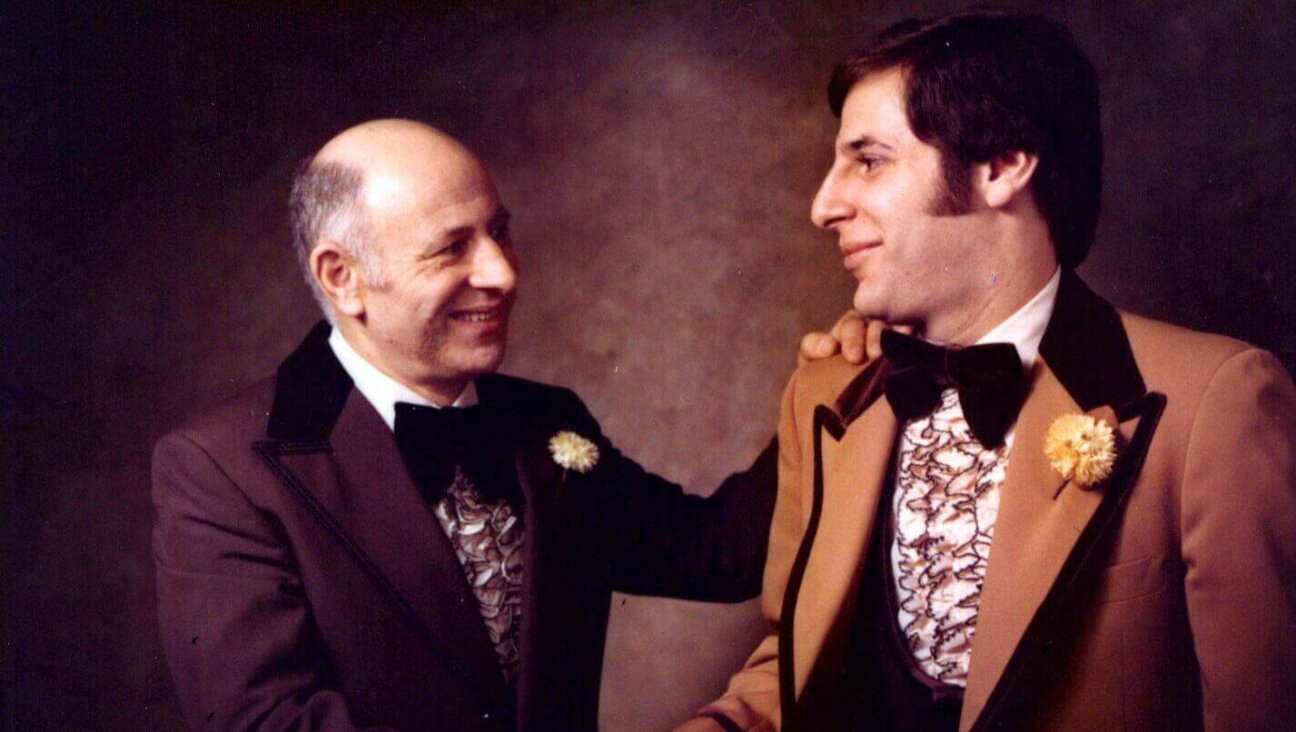

Image by Aaron Tessler

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

In the summer of 2012 Aaron Tessler, a student at Johns Hopkins University, visited his grandmother Rachel Tessler in Tel Aviv. A 93-year-old Holocaust survivor, Mrs. Tessler regaled her grandson with stories of her childhood in the Transylvanian village of Romuli.

Although Romuli, located in Bistrita-Nasaud County, Romania, was quite small, it boasted a vibrant Jewish community. Prominent Hasidic rebbes, including the Vizhnitzer, often visited Romuli to spend Shabbos with their followers.

Rachel also sang him some of the Yiddish songs she had learned there. At first Aaron recognized all of the songs from the many albums of Jewish music he had listened to as a child growing up in Norfolk, Virginia. But then she started to sing a song he had never heard before – “In Vildn Vald” (In the Wild Forest).

He took out his iPhone and hit record.

Thanks to his eight semesters of Yiddish at Johns Hopkins, he readily understood the song’s lyrics, which describe how a lamb named “S’rolikl,” i.e. Israel, a metaphor for the Jewish people, is threatened by a series of vicious beasts in a dark primeval forest. The song ascribes the lamb’s terrible fate to the Jewish people’s lack of a nation to call its own.

Upon returning to America, Aaron delved into archives and databases of Jewish music, searching for his grandmother’s song. Eventually, he found a single recording of “In the Wild Forest.” The version, sung by an unidentified man, was quite distinct from his grandmother’s. Aaron was unable to track down any further information about where or when the recording was made.

Rachel Tessler passed away five years later at the age of 97. Her death reminded Aaron of the song. “With God’s help, I’ll make a professional recording of ‘In Vildn Vald,’” he thought.

Jewish music is a longstanding tradition in Aaron’s family. After surviving Auschwitz and a series of death marches, Rachel Tessler returned to Romania, where she married Baruch Tessler, a great lover of cantorial music. The couple, along with dozens of fellow survivors, settled in the town of Viseu de Sus, in Maramures County. There, some 34 kilometers from the little village of Romuli where she was raised, Rachel Tessler gave birth to her son Jacob.

Jacob Tessler grew up surrounded by Jewish music and became a cantor. His son, Aaron, followed in his father’s footsteps: at 16 he began leading Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services at his synagogue in Norfolk, Virginia. At 18, while a student at Johns Hopkins, he began performing at weddings and bar mitzvahs in Baltimore.

With a beautiful voice, music in his blood, and four years of Yiddish studies under his belt, Aaron felt he could do justice to his grandmother’s song. But making a professional recording requires a lot of help. So Aaron launched a GoFundMe, turning to relatives, friends and the wider community of Jewish music aficionados for support.

Once his project was financed, Aaron focused his attention on the finer details of producing a professional recording. For that he turned to Yoily Polatseck, director of the Monsey-based Zemiros Choir.

“Because we were starting with almost nothing—just a recording—we needed to figure out everything from scratch,” Tessler told the Forverts. “We had to decide how quickly it would be sung and what style to sing it in. That was difficult, of course.”

“On the other hand,” Aaron continued, “because we had so little to go on we could rework it and make it new. This song was essentially dead; nobody was singing it anymore. So it fell to me to revive it.”

Originally, Aaron hadn’t planned to record the song with a choir. Later he saw it in a new light, recasting it as something that might have been sung at a Hasidic tish (a social gathering with a rebbe). He composed a niggun, a wordless melody inspired by the song, which the Zemiros Choir performed with him on the recording. Shloimy Salzman, a sought-after musical arranger, took the various musical threads—the song’s original folkloric melody, the cantorial elements, the choir’s singing and the niggun Tessler had composed—and weaved them all together.

“I couldn’t have done it without them,” Tessler said, referring to Polatseck and Salzman.

And so, two years after Rachel Tessler’s death and some 90 years after she first heard “In Vildn Vald,” Aaron Tessler released his new recording of the song from his grandmother’s childhood. Aaron arranged for the song to be distributed within the Hasidic community and promoted it on Hasidic blogs and Youtube channels so that this unique piece of prewar Jewish culture that he helped to rescue would not be forgotten.

“I’ve gotten really great feedback,” Aaron said. “People said that it sounded ‘heymish’ (authentic, homelike, or Hasidic), like something their own grandmother might have sang.”

Aaron hopes that others will continue to sing the song, which until recently he and his grandmother were the only people in the world to know.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO