Remembering Archivist and Warsaw Ghetto Survivor Rose Klepfisz

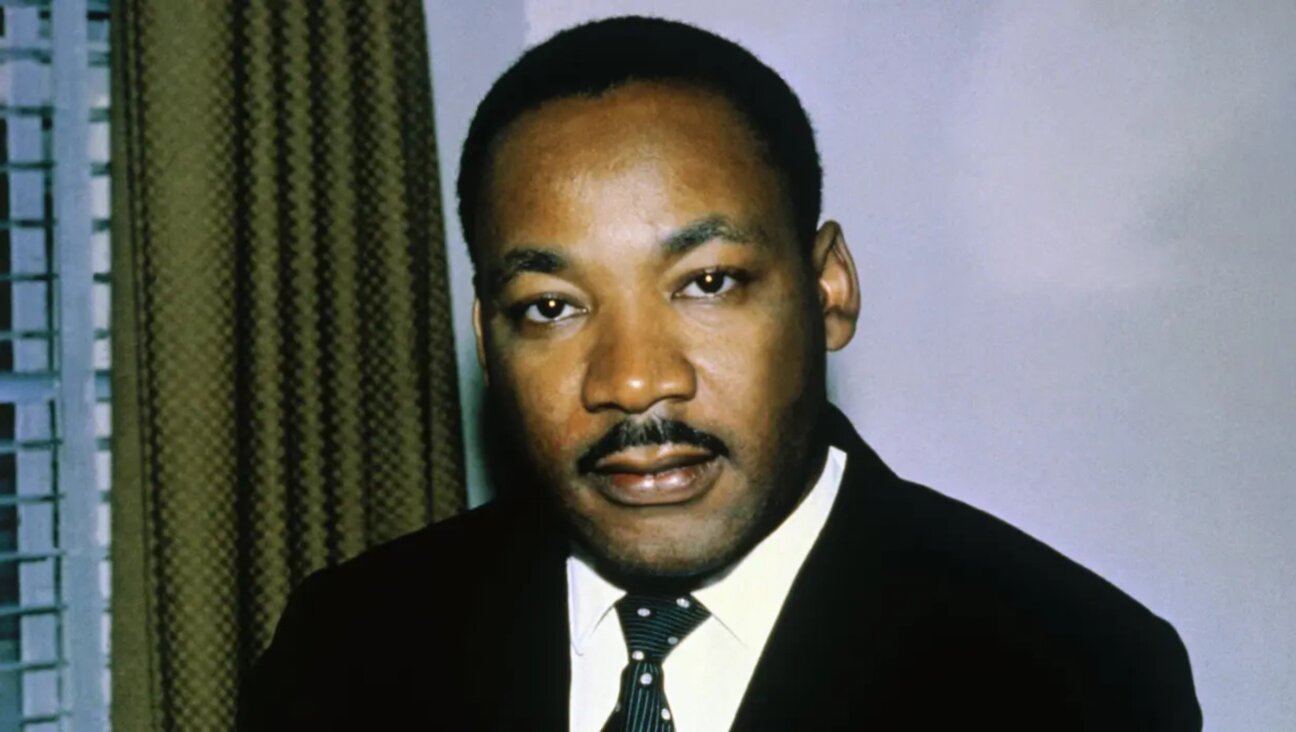

Archival Photo: Rose Klepfisz (bottom row, second from right) Image by Yivo Institute for Jewish Research

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

The archivist Rose Klepfisz died in her apartment in the Bronx on March 23rd at the age of 102. She is survived by her daughter, Irena Klepfisz, a writer and professor at Barnard College, as well as by relatives in Australia and admirers in Bundist circles and in the field of Jewish Studies around the world. She is predeceased by her husband Michal Klepfisz, who died fighting in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Rose Klepfisz was born on July 22nd 1914 in Warsaw as Shoshana Perczykow. At the insistence of her older sisters, she attended Polish public schools rather than private Jewish schools. The perfect Polish that she learned in school would greatly aid her during WWII. The death of her father, a clockmaker, when she was 12 forced her to leave school prematurely as her family needed the money her sewing could bring. A lifelong lover of literature she continued her studies by taking night classes at a local library. During her teenage years, she was an active member of the Zionist movement Hashomer Hatzair’s youth group and learned to plant tobacco in preparation for a new life in British-Mandate Palestine.

Her politics would change, however, after she met her husband Michal Klepfisz during a skiing trip. Michal spotted her from a distance and chased her down a hill. The two dated for four years before marrying in July of 1937. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon in Paris and soon moved into the home of Michal’s parents, the Bundist activists and teachers Miriam and Jakob Klepfisz. The Klepfiszes were more well-off than Rose’s family and she enjoyed the relative luxuries that their home provided such as a bathtub. In the years before WWII Michal worked as a chemical engineer and was rising in the ranks of the Bund, helping to run the movement’s sports club Morgenstern.

Rose Klepfisz was already pregnant when she was confined to the Warsaw Ghetto alongside nearly half a million of her fellow Jews. She gave birth to her daughter Irena on April 17th, 1941, her husband’s 28th birthday. The young family continued living with Michal’s parents and older sister until they were all lined up in a courtyard during a selection. At the last possible moment, Michal recognized a Jewish policeman he knew and managed to create a diversion, sneaking himself, his wife and his daughter out of harm’s way. The couple soon learned that Michal’s parents had been brought to the umschlagplatz, from which they were put on a transport to Treblinka and murdered.

In 1942, Michal Klepfisz himself was sent on a transport to Treblinka but before arriving, he managed to break through the metal covering a window and jump out of the train. After sneaking back into the ghetto, he joined the Jewish Combat Organization, the ghetto’s underground resistance movement. Thanks to his knowledge of chemistry, he was put in charge of making explosives for the Jewish resistance and created a secret bomb factory. He, along with Yitzhak Zuckerman (known by his nom de guerre Antek) and Izrael Chaim Vilner (known by his nom de guerres Arie and Jurek), also served as a key liaison between the Jewish resistance fighters and the underground Polish Home Army. The three emissaries for the Jewish resistance fighters arranged for the Polish Home Army to provide the Jews with guns and helped to smuggle the weapons into the ghetto. At the same time Michal Klepfisz made arrangements through his underground contacts to save his wife and daughter. He managed to obtain false papers for Rose and have her placed as a servant working for a Polish family on the Aryan side of the city under the name Lodzia. Their daughter was placed in the care of a Catholic orphanage within the city limits.

On April 17th, 1943, two days before the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Michal left the ghetto to see his wife. That day, Michal’s 30th birthday and Irena’s 2nd, would be the last time Rose ever saw her husband. Three days later he would be killed shielding his comrades from machinegun fire.

“What did she think and feel when someone brought her the news?” Irena Klepfisz asked rhetorically during her eulogy at her mother’s funeral. “My mother was not even 29 years old; her 2-year-old was unreachable in a separate hiding place. She was alone facing the war machine; she would now have to make her own decisions. And she did.”

A year later during the Warsaw Uprising, Rose learned that the orphanage where her daughter was living would be relocated outside of the city. She left the safety of her hiding place and spoke with the nuns. “They wouldn’t give me back to my mother,” Irena Klepfisz recalled in an interview with the Forward. “So she simply kidnapped me and we left Warsaw.”

Cut off from her contacts, Rose hid with Irena outside the city. Both soon fell ill due to the effects of starvation. After months of isolation, she ran into a woman who looked familiar. It turned out to be Helena Sheffner, a Bundist comrade who had been her husband’s French teacher. Helena put Rose in contact with underground Bundist resistance members who brought her and Irena food.

After the war, Rose settled in Lodz and lived with other Bundist survivors. Thanks to the intervention of the Jewish Labor Committee in New York, she was able to leave Poland and settle in Neglinge, Sweden. There she sewed children’s clothes for department stores and began to learn English in preparation for her planned immigration to Australia, where her brother and sister had settled after escaping Warsaw (her mother and three sisters were murdered during the Holocaust).

She arrived in New York in April 1949 on a seven-day transit-visa. After speaking with one of her husband’s surviving relatives who lived on Riverside Drive she decided not to continue on to Melbourne but to stay in New York. She moved into the Amalgamated Houses in the Bronx where she was warmly welcomed by the apartment complex’s large contingent of Bundist refugees.

“It was a wonderful community there,” Irena Klepfisz recalled. “That whole group from Europe, these Bundists had known each other from before the war. Most of the people we knew from Sweden ended up in the Amalgamated Houses. They constantly talked about their lives in Europe and about the Bund; not about the war itself but about the history of the prewar years, about a time that was filled with so much optimism, so much possibility of what might be.”

Although Rose Klepfisz would begin her working life in New York as a seamstress, she soon earned the opportunity to help preserve the world of Eastern-European Jewry. Despite the fact that she had no training as an archivist, the esteemed Holocaust historian Phillip Friedman, the director of the Joint Documentary Projects at Yad Vashem and the YIVO Institute, recruited her to work on YIVO’s pioneering Holocaust bibliography the Guide to Jewish History Under Nazi Impact. A mere decade after escaping the Warsaw Ghetto, Rose spent every day reading detailed reports about the extermination of European Jewry in order to catalog them. “I remember her coming home exhausted and deeply depressed and saying: If you only knew what I read today,” Irena Klepfisz recalled of the period in her eulogy.

The emotionally draining work at the YIVO Institute proved to be a fertile training ground and Rose soon became a skilled archivist. In 1962, her supervisor at YIVO Dr. Jacob Robinson, recommended her to the Joint Jewish Distribution Committee as a candidate to be their first archivist. It wouldn’t be an easy task. The Joint hadn’t properly maintained its archives; as the journalist Harold Epstein described in a letter in 1960 to the organization’s Chairman, the collection was an impenetrable “jungle of records… Only the most intrepid soul would set forth into that forest of paper.”

The documents, kept in a warehouse in Brooklyn, were in such terrible shape that Rose had to bring a folding iron to work in order to smooth out the pages. Over the course of the following 23 years, she systematically sorted and ordered hundreds of thousands of documents and created bibliographic guides to them. The records not only detailed the Joint’s work but also revealed a stunning portrait of the vibrancy of prewar Jewish life in Poland. Rose also hired and trained other archivists, including her friend the ethnomusicologist Chana Mlotek, to work in the JDC’s archives. The academic world soon recognized her extraordinary work. Among the scholars who have thanked her for making their own research possible are such academic giants as the Holocaust historians Yehuda Bauer, Lucy Dawidowicz and David Wyman.

In a condolence letter to Irena Klepfisz, Linda Levi, the Assistant Executive Vice President of the JDC and Director of its global archives, wrote that Rose Klepfisz’s “Herculean effort” had made the organization’s archives accessible for the first time, positioning it as “one of the foremost archives in the world for modern Jewish history… JDC’s worldwide staff and generations of researchers across the globe are beneficiaries of your mother’s foresight, dedication and commitment to the Jewish people and to the preservation of Jewish history. She is a towering figure in JDC’s history.”

After retiring from her job at the JDC, Rose Klepfisz remained an active member of the Bund and the Workmen’s Circle. Although she worked diligently to ensure that the memory of her husband and his fellow Warsaw ghetto fighters would never be forgotten, she declined to speak at any public memorial ceremonies or give interviews about her wartime experiences. “She was very private about all of that,” Irena Klepfisz said.

Besides her professional career as an archivist, Rose never ceased to make clothing, signing each new outfit “A Rose Klepfisz Original.” She also greatly enjoyed theater and remembered the Polish poetry she had learned in elementary school by heart. She befriended multiple generations of American-born Yiddish writers, musicians and actors at Bundist events and later at Klezcamp. Known for her warmth and sense of humor she served as a bridge between postwar America and the lost Jewish Warsaw of her youth.

A Yiddish version of this story was published in the Forverts on April 3rd

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO