Medieval Jewish Meal in Italy Resurrects Menus

In a medieval tavern in 21st century Italy, waitresses in archaic costumes served a tepid, chalk-white substance the texture of oatmeal to tables filled with slightly skeptical diners.

Sweet yet salty, and flavored with a mix of unexpectedly tangy spices, it turned out to be a tasty puree made from shredded chicken breast, almond milk, rose water, cloves and rice flour.

The dish was a savory form of biancomangiare, or almond pudding, a food that was popular in Italy in the Middle Ages. Jews back then loved it, too, food historians say, and often called it “almond rice.”

On this recent night in Bevagna, an ancient walled town in central Italy’s Umbria region, biancomangiare was being served as the first course of a special kosher-style dinner aimed at re-creating a meal that Jews in Italy would have eaten in the 14th and 15th centuries.

On this recent night in Bevagna, an ancient walled town in central Italy’s Umbria region, biancomangiare was being served as the first course of a special kosher-style dinner aimed at re-creating a meal that Jews in Italy would have eaten in the 14th and 15th centuries.

It was followed by a spicy lentil soup and then the main course: heaping platters of crisp, twice-roasted goose with garlic served with a warm salad of baked onions in sweet and sour sauce. The meal was rounded out by a form of spiced white wine called ippocrasso and honey-nut sweets served on fresh bay leaves.

“We love medieval cooking,” said Alfredo Properzi, one of the dinner organizers. Properzi, a local doctor, belongs to a civic association that fosters study and re-enactment of life in the Middle Ages. The recipes for the dinner, he said, came from cookbooks of the period.

“One of the big differences was the spices that they used – much more than today,” he said. “Also, medieval cooks liked to use various spices to color food as well as season it.”

The dinner added flavor – literally – to an academic conference on medieval Jewish life in Bevagna, a town where Jews lived from the early 14th century until they were expelled from all of Umbria in 1569.

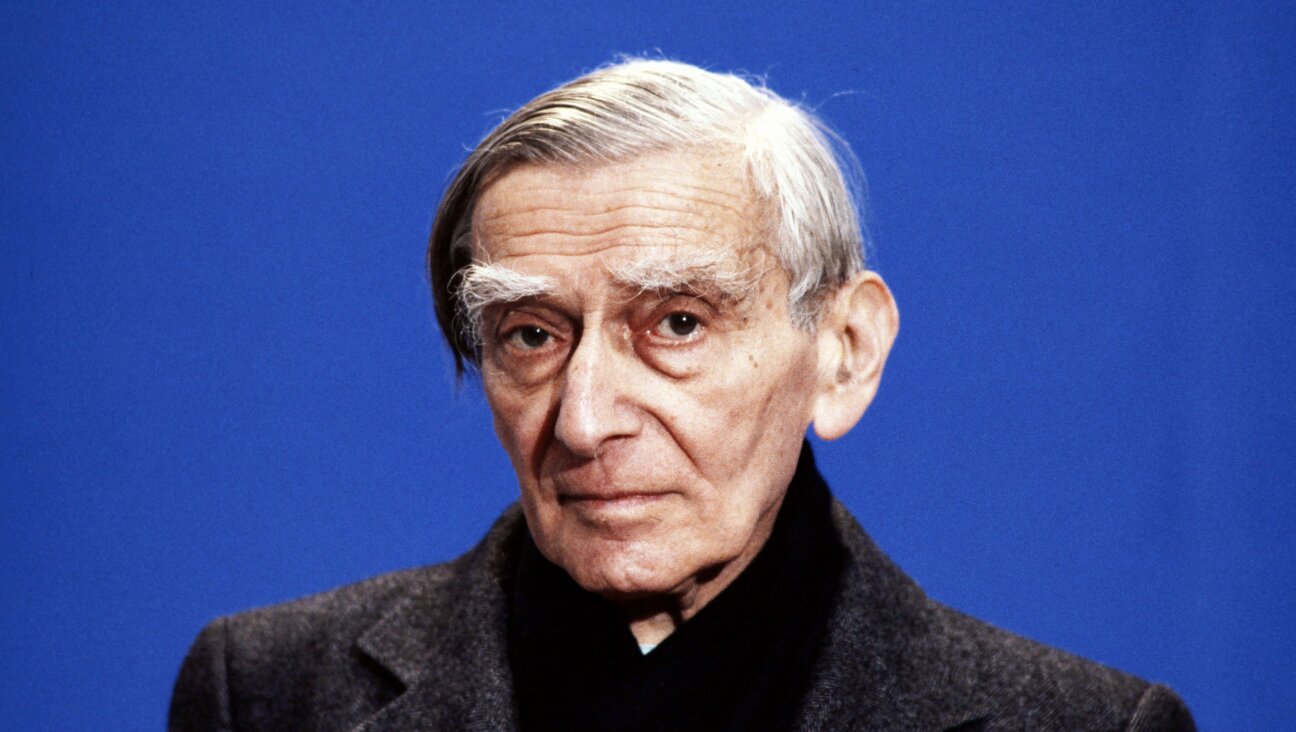

“There were probably never more than two or three Jewish families in Bevagna,” Bar-Ilan University historian Ariel Toaff, the main conference speaker, told JTA as he sampled the dishes and sipped the strong local wine, Sagrantino di Montefalco.

“It would have been impossible to maintain a kosher slaughter house for so few people,” he said. “If they wanted meat, they would have had to get it from another town, or they would have eaten poultry, which could be slaughtered at home.”

No Jews today live in Bevagna, and only a few dozen Jews live in all of Umbria. But historic documents provide fascinating insights on many aspects of medieval Jewish life, from food and wine to religious observance, sex, love and marriage, economic life and, of course, discrimination.

Particularly extensive archival material details the dramatic family saga of the most prominent Jews who lived in Bevagna in the 15th century, the banker Abramo and his large, extended clan.

Abramo owned banks in three towns, as well as a mansion, investment properties, farmland and many other holdings. But after his death in 1484, the family suffered a series of tragic setbacks, including deaths, bank failures and even a trumped-up claim by a young Bevagna boy that the family had lured him to their home and crucified him over Easter in 1485. Though apparently linked to a default on a loan to the Abramo bank by the boy’s mother, the allegations led to the banishment of several Abramo family members.

The dramatic tale and long-gone Jewish presence in Bevagna have kindled interest in a town that already revels in its medieval history. Bevagna hosts medieval events throughout the year, and each June the entire town is given over to a medieval festival featuring food, costumes, artisan workshops, entertainment and historic reenactments.

The town co-sponsored the medieval Jewish life conference that featured the dinner, and Bevagna Mayor Analita Polticchia told JTA that she would like to take things even further.

“We are thinking now of adding Jewish components to our annual medieval festival,” she told JTA between courses. “Maybe we can even see about getting a kosher winery started up.”

Toaff, the son of the retired longtime chief rabbi of Rome, was key to organizing the Bevagna dinner. Though he gained notoriety a few years ago for a book suggesting that the medieval blood libel myth may have been fueled by the actions of small groups of Ashkenazic Jewish extremists carrying out revenge killings against their persecutors, his main work has focused on medieval Jewish life in Umbria. He also authored “Mangiare alla Giudia” (“Eating Jewish Style”), an influential history of Jewish cooking in Italy.

“The dinner organizers asked me what would be a typical dish for the menu, and I immediately told them goose because goose was, so to speak, the Jewish pig,” Toaff said. “It had the same function for the Jewish table as the pig did for non-Jews. Every part of the animal was used, including for goose salami, goose sausage and goose ‘ham,’ and foie gras was also a Jewish specialty.”

Like today, he said, Jews in medieval times generally ate what the non-Jewish population did, adapting local recipes to the rules of kashrut.

“Biancomangiare was also made sweet with milk, pine nuts, almonds and raisins,” Toaff said. “But if it was served with a meat dish, the Jews would substitute almond milk for dairy milk.”

Also like today, certain dishes became Italian Jewish favorites.

“Lentils were typically Jewish, and lentil soup was commonly eaten in the 14th and 15th centuries,” Toaff said. “Being round, they symbolized the cycle of life. Another typical Jewish cooking style was sweet and sour, like the baked onion salad.”

Written recipes dating back nearly 500 years exist for one of the most famous Italian Jewish dishes, sweet and sour sardines, or “sardele in saor,” made with onions, olive oil, cloves, pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon, rosemary, raisins, pines nuts, sweet wine and candied citrus peel.

“White sugar was considered a spice,” Toaff said. “And salt and pepper were expensive because they served as ‘refigerators’ – they preserved food, and they also hid any spoilage.”

He added, “What is interesting in addition to what Jews ate in the middle ages is what they didn’t eat – corn, potatoes and tomatoes, which had not yet been imported from the Americas.”

Biancomangiare

(The recipe is from Libro de arte coquinaria by Maestro Martino. See http://www.cucinamedievale.it/2009/12/biancomangiare-alla-catalana/)

150 grams of peeled almonds

25 grams of rice flour

1/2 liter of chicken broth

150 grams of boiled chicken breast

5 centiliters of rose water

Ground ginger, cinnamon and cloves

Grind or finely mince the chicken breast. Grind (or crush with a mortar and pestle) the almonds, and dissolve with the rice flour in the chicken broth. Strain this to obtain a milky liquid. Bring this to a boil and add salt to taste. Add the minced chicken and simmer, stirring until the mixture thickens to the consistency of a thick cream. At the end of the cooking, add the rose water. Serve lukewarm, sprinkled with the spices.

Baked Onion Salad

(The recipe is from a 14th century cookbook.

2 pounds medium-sized sweet onions

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon wine vinegar

Pinch of ground black pepper

Salt to taste

Pinch of a mixture of cinnamon, ginger, saffron, and cloves

Wrap the onions individually in foil and bake for about an hour at a high heat. Open the foil and let cool until lukewarm, then remove the blackened outer skin. Cut the onions into slices. Place in a salad bowl and dress with the salt pepper, spices, oil and vinegar. Bake the onions dressed sauce of olive oil, vinegar, black pepper, cinnamon, ginger, saffron and cloves. (You can also use small onions and serve them whole rather than slice them.)

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO