How a religious revival fed the demise of the Midtown kosher deli

A scholar of the Jewish deli explores the merger of Ben’s and Mr. Broadway

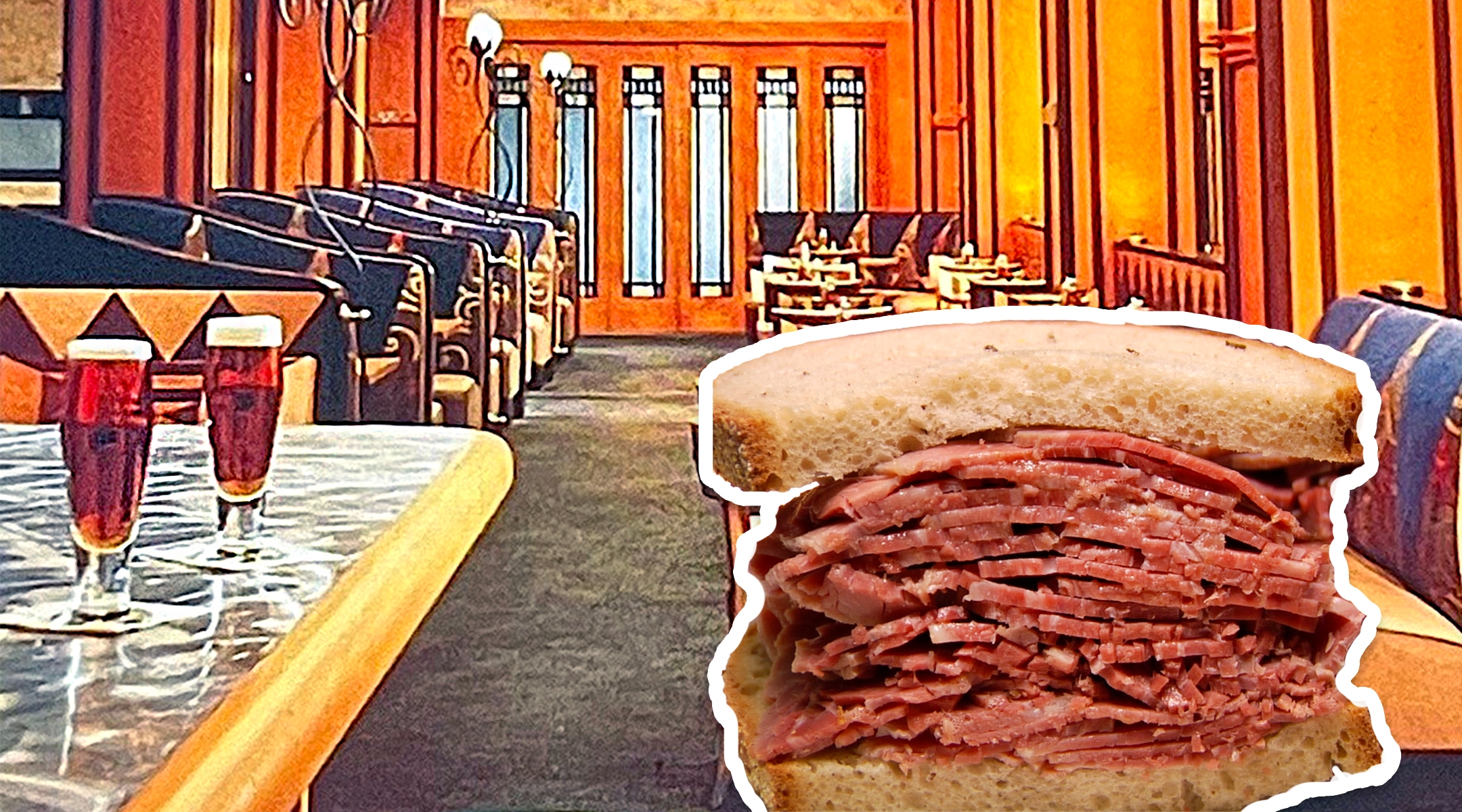

The faux Art Deco interior of the former Ben’s Kosher Deli in Manhattan. (Courtesy Ben’s; JTA illustration by Grace Yagel)

(New York Jewish Week) — It happened toward the end of the last theater season, and it didn’t occasion much comment in the media. But the merging of Ben’s Kosher Delicatessen on West 38th Street with the glatt kosher Mr. Broadway around the corner marked the end of an era.

Ben’s, the last kosher deli in the Theater District that was open on Shabbat, made it possible for generations of Jewish New Yorkers — and a good many Jewish tourists as well — to enjoy a bowl of matzah ball soup and a kosher pastrami or corned beef sandwich before heading to a Saturday matinee.

In recent years, as the Orthodox world has become increasingly stringent, fewer and fewer agencies have offered kosher supervision to an eatery that remains open on the Jewish Sabbath. But all sorts of Jews eat in kosher restaurants for all kinds of reasons: nostalgia, a continuing attachment to Jewish culture, a sense of fealty to the Jewish people, a desire to be among other Jews, or even simply force of habit.

The merger of Ben’s and Mr. Broadway may represent a triumph of religiosity, but it also marks the demise of a Midtown kosher culture that was more flexible and more inclusive of the diverse ways people experience their Jewishness.

Kosher delis were, for decades, fixtures of the Garment Center and the Theater District — the twin neighborhoods, both heavily trafficked by Jews, that stand cheek by jowl in Midtown. Hirsch’s Kosher Deli on West 35th Street was immortalized in the early 1940s in a photo by Roman Vishniac of a group of clothing company executives in three-piece suits and fedoras reading Yiddish newspapers and chatting — a far cry from the photographer’s iconic shots from less than a decade earlier of impoverished Eastern European Jews, most of whom were fated to perish in the Holocaust.

In the 1960s, kosher delis in the area included the Melody on Seventh Avenue at 37th Street and Golding’s on Broadway and 48th Street (before it decamped to the Upper West Side, reopening at Broadway and 86th Street). In the 1970s, the Smokehouse on 47th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues featured smoked and spiced beef by Zion Kosher, the main rival in New York to Hebrew National.

Celebrated Theater District delis like Lindy’s and Reuben’s, and later The Stage and The Carnegie, weren’t kosher, and they sold the lion’s share of corned beef and pastrami sandwiches.

But there was no dearth of kosher food in the neighborhood. In addition to the kosher delis, there were popular upscale kosher eateries like Gluckstern’s — which claimed, in the late 1940s, to serve a staggering 15,000 customers a week — Poliacoff’s, Trotsky’s, the Paramount and Lou G. Siegel’s, which billed itself as “America’s Foremost Kosher Restaurant.” Lou G. Siegel’s occupied the same space that Ben’s took over and that Mr. Broadway is in now at 209 West 38th Street. (Mr. Broadway originated as a dairy restaurant in 1922; in 1985, it transitioned to a gourmet glatt kosher restaurant, and over time added sandwiches, sushi, Israeli food and the like.)

In addition to serving steaks and chops, these establishments sold large quantities of deli sandwiches. While these restaurants advertised themselves as “strictly kosher,” they were open on Shabbat, although notices in their menus, printed daily, beseeched patrons not to smoke on the premises on Friday nights and on Saturdays until sundown, since that, of course, would be a flagrant violation of Jewish law.

When a 2018 review in the New York Times referred to the 2nd Avenue Deli as kosher, even though it was open on Shabbat, it prompted a complaint from a reader named Fred Bernstein. Bernstein explained to restaurant critic Frank Bruni that “almost no observant Jew would consider it kosher” and cited two authorities on the subject: actor Sacha Baron Cohen and Leah Adler, Steven Spielberg’s mother and then owner of a kosher dairy restaurant in Los Angeles.

Bruni responded, quite reasonably, that he has “several friends who adapt and interpret kosher dietary rules in unusual and permissive ways.” He added: “For them ‘kosher’ — and they do use the word itself when explaining their menu choices — isn’t an exact and exacting prescription so much as it is an ideal toward which they take small steps.”

Indeed Ronnie Dragoon, who owns the restaurants in the Ben’s Kosher Deli chain — all of which are open on Shabbat — and is now a part-owner in Mr. Broadway, estimated that only about 20 percent of his clientele, across all his restaurants, keep the Jewish dietary laws.

Most of the kosher delis in New York were historically open on Shabbat, from the heyday of the kosher deli in the 1930s, when there were a staggering 1,550 such delis in the five boroughs, to today, when less than one percent of that number remains. Deli owners needed their establishments to be open on the weekends to make a profit — in Manhattan, they did the bulk of their business on Friday and Saturday nights, as opposed to kosher delis in the outer boroughs, which were typically busiest on Sunday nights for both eat-in and takeout.

Some kosher delis, especially in the outer boroughs, did close for the entirety of the Sabbath. As Alfred Kazin writes in his lyrical memoir, “A Walker in the City,” “At Saturday twilight, as soon as the delicatessen store reopened after the Sabbath rest, we raced into it panting for the hot dogs sizzling on the gas plate just inside the window. The look of that blackened empty gas plate had driven us wild all through the wearisome Sabbath day. And now, as the electric sign blazed up again, lighting up the words JEWISH NATIONAL DELICATESSEN, it was as if we had entered into our rightful heritage.”

In Manhattan, many owners of kosher delis got around the strict rules of kashrut by “selling” their restaurants to non-Jews, usually employees, before sundown on Friday and buying them back on Saturday night, so they technically didn’t own them and so weren’t doing business during the Sabbath. (This echoes the practice that many Jews engage in by selling forbidden food items to a non-Jew before Passover.) Many justified staying open on Shabbat because it enabled Jews to remain faithful to Jewish tradition in their food consumption, without regard to other ways in which they were transgressing Jewish law.

Kosher delis nowadays adopt different strategies to deal with this issue. Some, like the 2nd Avenue Deli, do still sell their businesses to a non-Jew. Yuval Dekel, the owner of Liebman’s, the last kosher deli in the Bronx (which is about to debut a second store in Westchester) told me that he just ensures that all his ingredients are kosher and leaves it at that.

Some kosher delis, especially outside the New York area, like Abe’s Kosher Deli in Scranton, Pennsylvania, are owned by non-Jews. While relatively unusual, there is nothing new about this: The Kosher Irishman, a deli in East Orange, New Jersey, was open for more than a half a century.

Staying open on Shabbat in the city, however one did it, could be a problem if a neighborhood became heavily populated by Hasidic Jews. My mother worked in the 1950s in her uncle’s kosher deli in Williamsburg, Brooklyn until the restaurant was forced to close because of opposition from the growing haredi population in the neighborhood, who insisted that keeping an otherwise kosher restaurant open on Shabbat was a chillul haShem (desecration of God’s name).

In today’s world, in which most Orthodox Jews will eat only in glatt kosher delis like Mr. Broadway, Jewish food doesn’t play the kind of unifying role it once did, according to Jeffrey Gurock, a professor at Yeshiva University and a historian of Modern Orthodoxy. In the past, Gurock has explained, seeing a neon Hebrew National sign in the window made even Modern Orthodox Jews comfortable eating in a deli, whether it was open on Shabbat or not.

Early one Wednesday afternoon in July, I stopped at Mr. Broadway for a bite. I had a ticket to “Funny Girl,” so I didn’t have too much time to eat. I sat and chatted with Dragoon while I chowed down on a brisket sandwich and a potato knish. Two kippah-wearing businessmen were sitting at a nearby table and we took bets on what they would order, since it was during the Nine Days before Tisha B’Av and observant Jews refrain from eating meat during that time of year.

I glanced at a huge, framed oil painting that was sitting on the floor, leaning up against one of the walls that, when it was still Ben’s, was decorated with the famous deli joke about an immigrant Chinese waiter who speaks Yiddish (and thinks he’s speaking English). In its place, the oil painting showed a tall Orthodox rabbi standing on a plush red carpet before the ark in a synagogue; he was clad in sumptuous blue and white robes and sported a long, flowing white beard. The painting seemed like the perfect symbol of what had happened to the deli as it had acquired a depth of religiosity that neither Lou G. Siegel’s nor Ben’s had ever aspired to.

Ronnie saw me looking at it. “Do you want it?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “No, I really don’t.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO