Searching for Jewish Sicily, I returned with two Hanukkah recipes

Caponata alla giudia and panelle make for a perfect holiday meal

Caponata with fried eggplant Photo by @foodaism

We drove to Modica for chocolate and Jews. The chocolate we found, but the Jews, not a trace. Were we, like Rick in Casablanca, misinformed?

The woman in the tourist information office told us, dismissively, we would find no markers of the once-thriving Jewish community in the small Sicilian hilltop town. According to her, there probably were never even Jews there.

“These are legends,” she said.

We refused to believe her. We schlepped around for an hour, following a clue in an internet posting that on an archway by a church there’s a Hebrew inscription marking where the Jewish quarter used to be.

We asked locals, we doubled back, we marched up and down the steep streets until our tempers snapped. There are dozens of churches in Modica, and even more archways. Nothing.

Still, we knew she was wrong. Historians documented that prior to the Inquisition in 1492, about one out of 20 residents of Modica were Jewish, living in a hilly quarter across from the main church called il Cartellone. On Sunday, Aug. 15, 1474, a Dominican priest gave a fiery sermon denouncing the Jews, inciting a mob to ransack il Cartellone. The Modicans rampaged through the Jewish quarter screaming, “Long live Maria, death to the Jews!” apparently unaware that Jesus’ mother was, you know, Jewish.

They killed 360 Jews and drove many others out. Those who remained, not just in il Cartellone but anywhere in Sicily, were hounded out following the Inquisition.

We weren’t the ones who were misinformed. The Jews had been here.

But that’s the challenge of Jewish Sicily: You’re chasing ghosts. Remnants of Jewish life are there to be found, but after hundreds of years and so much forgetting, they speak in a whisper.

To me, they whispered through the food.

Take Modica’s chocolate. The city is famous for its coarse-textured chocolate, so of course we visited the chocolate museum on the third floor of a municipal building. The museum didn’t mention what some Jewish food experts surmise: that the Jews, who brought chocolate-making skills to France, also brought it to Sicily. One clue: a photo exhibit in the same municipal building of local Byzantine-era tombs, several of which were adorned with stone carvings of menorahs.

Sweet and sour

The Jews arrived in Sicily in the first century and were instrumental in building the island’s flourishing trade and mercantile systems. They mingled with the Arabs who conquered Sicily in the ninth century, bringing oranges, lemons, pistachio and sugar cane among other foods.

The Arab-Jewish influences — dishes that combine sweet and sour flavors, the use of eggplant, even olive oil — are difficult to tease apart. “The traditions imported to Palermo by the Arabs were maintained there by the Jews,” writes Mary Taylor Simeti in Pomp and Sustenance: 25 Centuries of Sicilian Food.

The one dish that speaks that history most clearly is eggplant caponata. Of course I’ve eaten it in Italian restaurants in America, but in Sicily, it is always on offer. Always. Lost in translation is that it was the Jews who popularized the eating of eggplant.

“What most people ignore is that the Sicilian caponata actually has Jewish origins,” writes Benedetta Jasmine Guetta, author of Cooking alla Giudia. In a few cookbooks the dish itself is called caponata alla giudia.

At our first dinner in Siracusa, at a small family-run spot called O’Scina, there it was: eggplant, onion, garlic with vinegar and sugar providing sweet and sour notes. In two weeks we would learn every variation of the dish: some grilled or roasted the eggplant, some – my favorite – deep-fried it. Some threw in pine nuts and raisins, others tuna or swordfish.

Eating caponata connected us to a deep Jewish past. Before the Inquisition, at least 10% of the population of the southeastern port town was Jewish. In the now-Judenrein Jewish quarter, the Giudecca, we joined a small group of tourists and descended a staircase inside a hotel to arrive at the remains of three mikvahs, which once served the men, women and the rabbi’s family.

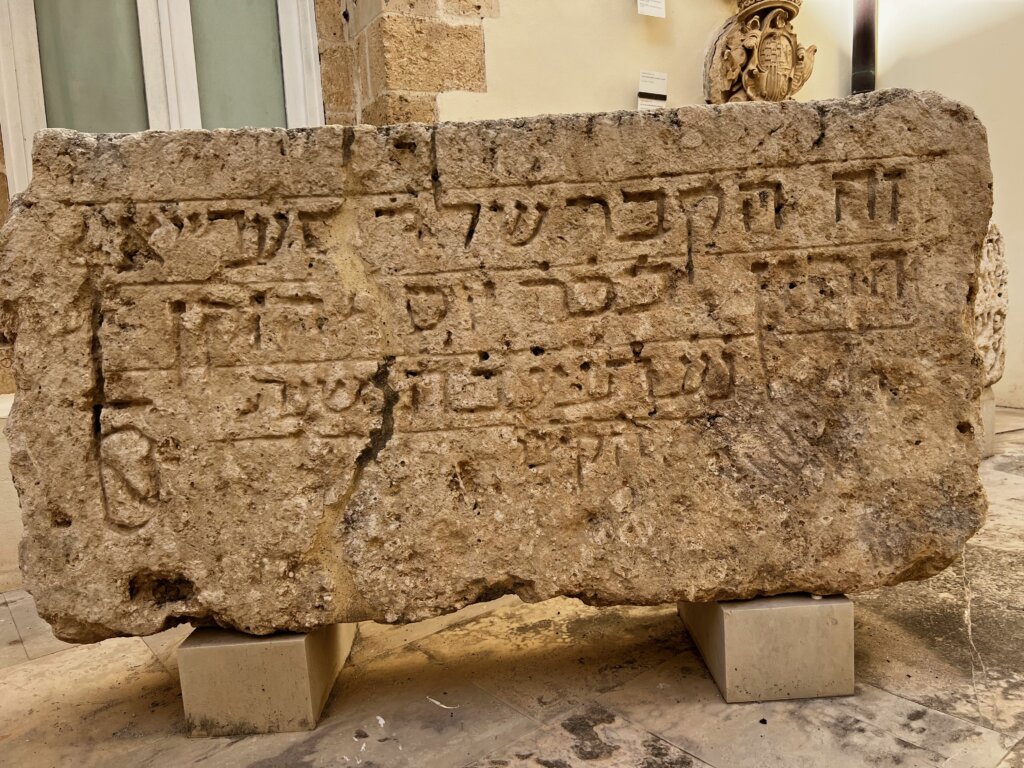

Nearby stood the four walls of a large roofless church of San Giovanni Battista, built on the remains of what had been the quarter’s main synagogue. The only sign of a once major Jewish community was farther down the street at the Regional Gallery at Palazzo Bellomo, where four tombstones, taken from a Jewish cemetery and once used to build a seawall, were on display in the courtyard. We translated their faded Hebrew descriptions. “On the fourth day of the Month of Tevet in the year 5187, the young Ester daughter of the honorable Rabbi Shabetai was buried. May she rest in Eden.”

Traveling on from Siracusa toward Palermo, it was easy to see how Sicily felt like home to the Jews.

The signs are everywhere

The late Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua campaigned to have Palermo, whose name comes from the Arab name for the city, Balarm, serve as the capital of a Mediterranean confederation of Arab countries, Andalusia and Israel.

“As I rapidly approach the end of my life,” he wrote, “the idea of forging a Mediterranean identity has become fundamental and of great importance to me.”

The idea always struck me as quixotic and arbitrary — Palermo? — until we arrived in the city. The climate is closer to Israel than Europe. Arab culture suffuses architecture, food and language. It’s Israel without the religious strife — or rather, centuries after the strife.

Again, the clues were in the foods. In the Ballaro market, fry shops offered squares of deep-fried chickpea flour called panelle. For a couple of euros you get four pieces stuffed into a split roll, doused with salt and pepper. It was warm, crisp and comforting.

Panelle are as ubiquitous as caponata in Sicily. Chickpeas originated in Turkey and made their way through the Middle East and then Europe, arriving long before the Jews and Arabs. But the deep-fried preparation spoke of a Mideast influence.

Jews once made up 5% of Palermo’s population. The Giudecca, just outside the old city walls, has recently been marked with Hebrew and English signs for tourists. Aside from that, there are few traces. But if you know where to look, the signs are everywhere.

“That’s where they were tried and tortured,” said our guide, Bianca Del Bello, who specializes in the city’s Jewish past.

She was pointing to the city’s main cathedral, a massive, stunning edifice across from our hotel. Tourists walked the ramparts and crowded the plaza, as unaware as we had been of its gruesome Jewish past.

Del Bello pointed out a church in the former Jewish quarter built on the site of what a medieval Jewish traveler once called the grandest synagogue in the world. And she pointed to another church, now shuttered, which was returned to Palermo’s two dozen or so Jews in a sign of penance and reparation by Palermo’s archbishop, Corrado Lorefice.

In the market, Del Bello said that Jews once worked as butchers and made sandwiches out of the inexpensive entrails they didn’t sell. Those somehow evolved into pani Ca’meusa, in which pieces of lung, spleen and intestine are boiled, fried in lard, and slopped on a roll with some ricotta. Food historians differ on how exactly the popular sandwich developed, but Del Bello hinted at antisemitism, which, given the ingredients, seems about right.

My favorite part of the second season of White Lotus, the popular HBO series which takes place in Sicily, is when the Italian American visitors travel to their ancestral village only to be chased out. My wife and I don’t have Italian heritage, but it was hard not to feel connected to Sicily’s Jewish past, centuries after the Jews, all of them, were chased out. All Jewish travel, after all, is roots travel.

It struck me, with Hanukkah approaching, how much Sicilian food with Jewish roots is fried. The best caponata we had – and we ate a lot of caponata — used deep-fried cubes of salted eggplant. Those panelle — also fried. I decided that when we returned to LA I’d be including both on our Hanukkah menus, when eating fried food is traditional. That would be, I figured, a way to resurrect a once great Jewish community, at least in my kitchen.

Caponata alla Giudia

“What most people ignore is that the Sicilian caponata actually has Jewish origins,” writes Benedetta Jasmine Guetta, author of Cooking alla Giudia, which includes this recipe. Guetta essentially deep fries the eggplant cubes, caramelizing them, so they add their own sweetness to the final dish. The not-insubstantial amount of olive and vegetable oil this recipe calls for makes it perfect for Hanukkah, though you’ll have to seek eggplant and tomatoes from warmer climates, or a greenhouse.

Serves 4

3 medium eggplants

Kosher salt

1 1/2 onions

2 celery ribs

5 cherry tomatoes

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, smashed

1 cup chopped ripe tomatoes or canned diced tomatoes, with their liquid

2 tablespoons mixed black and green olives, pitted

1 tablespoon capers

1/2 cup white wine vinegar

1 tablespoon sugar

Sunflower or peanut oil for deep-frying

Freshly ground black pepper

5 basil leaves

- Cut the eggplants into 3/4-inch cubes. Transfer them to a colander, salt generously, weigh them down with a plate and let drain for 30 minutes in the kitchen sink.

- Cut the half onion into very thin slices. Cut the whole onion into chunks roughly the same size as the eggplant cubes. Cut the celery into chunks and cut the cherry tomatoes in half.

- Pour the olive oil into a large nonstick skillet set over medium heat, add the sliced onion and garlic and cook for about 3 minutes, until the garlic is slightly browned. Add the celery, tomatoes (both cherry and chopped), olives, capers and the chopped onion to the skillet and cook for 10 minutes, until the vegetables begin to soften. Add the vinegar and sugar and cook for another 10 minutes. Remove from the heat.

- Remove the plate covering the eggplant and squeeze the eggplant in the colander to remove any remaining liquid.

- Pour 1 inch of sunflower or peanut oil into a large saucepan and warm over medium heat until a deep-fry thermometer reads 350 F. You can test the oil by dropping a small piece of food, such as a slice of apple, into it: If it sizzles nicely but doesn’t bubble up too wildly, the oil is ready.

- Add only as many eggplant cubes to the pan as will fit in a single layer without crowding and fry until golden, turning often. Remove the eggplant with a slotted spoon and spread out on a paper towel-lined plate to drain. Cook the remaining eggplant cubes in the same manner, adding more oil if needed.

- Once the fried eggplant has drained, add it to the skillet of vegetables. Season with 1/2 teaspoon salt and pepper to taste, adding a bit of water if the vegetables look dry, and cook the caponata over medium heat, stirring frequently, for 5 minutes.

- Stir in the basil leaves, remove from the heat and let the caponata cool to room temperature before serving.

Excerpted from Cooking alla Giudia: A Celebration of the Jewish Food of Italy by Benedetta Jasmine Guetta (Artisan Books). Copyright 2022. Reposted with permission.

Panelle, or fried chickpea squares

These fried chickpea squares speak to Sicily’s Middle East influences. Try serving them with caponata.

Ingredients

1 ½ cups chickpea flour

3 cups water

1 teaspoon coarse sea salt or kosher salt

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

Vegetable or canola oil for frying

Instructions

- In a medium saucepan, whisk together the chickpea flour, water and salt. Place over medium high heat and cook, continue stirring, until the mixture bubbles, becomes thick, and easily pulls away from the bottom and sides of the pan. This can take 5-10 minutes. The mixture should be very thick or else it will break apart when frying. Remove from heat and stir in the parsley.

- Use a spatula to scrape and pour the mixture out into a parchment-lined pan, about 12 by 15 inches. A bench scraper or spatula will help you smooth the top to make it flat and even, about 1/4 inch thick. Place in the refrigerator to cool and harden.

- When you’re ready to fry, heat 1/2 inch of vegetable oil in a cast iron or other sturdy pan. The temperature should read about 375 F.

- Cut the panelle into squares, about 3 inches across. Lower carefully into oil without crowding the pan. Fry until brown, about 2-3 minutes, then flip and finish frying on the other side, another 2-3 minutes. Remove with slotted spoon and let drain on a paper towel-lined plate.

- Serve hot, sprinkled with some additional salt and pepper.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO