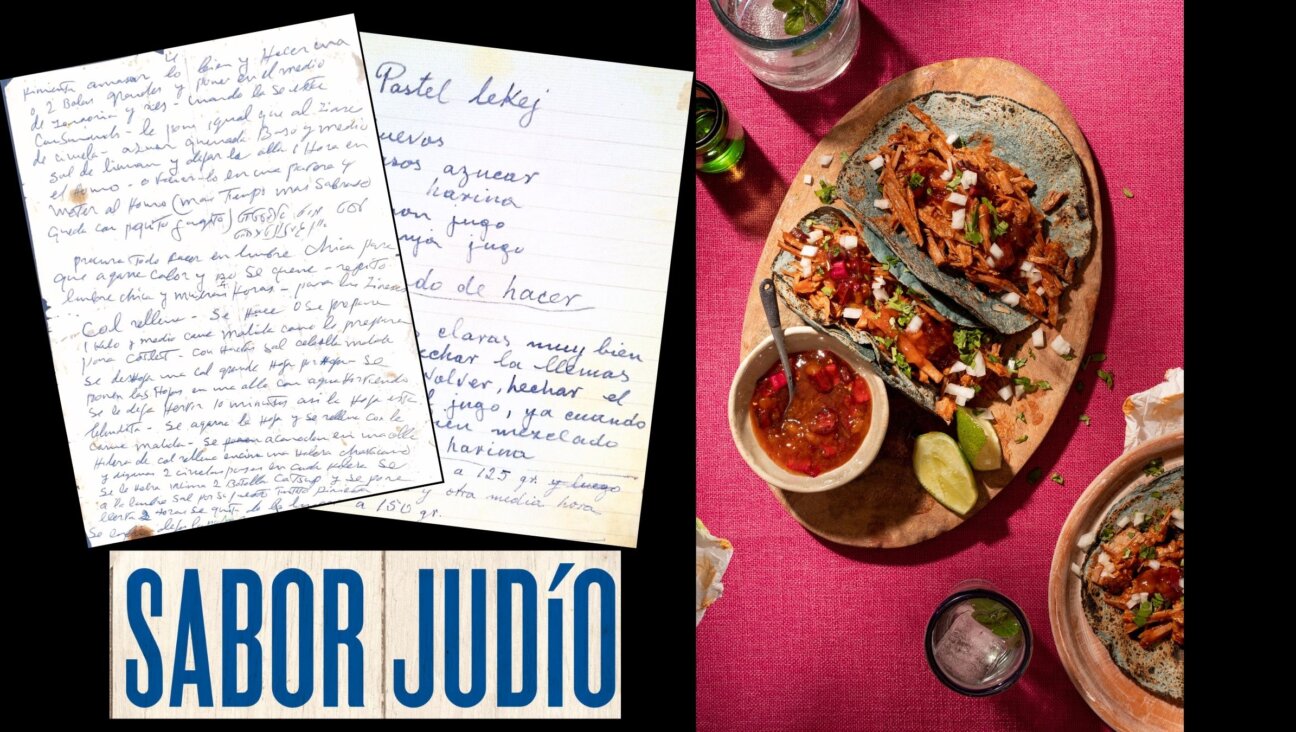

This Holocaust Survivor’s Shabbat Dinner Cooking Videos Are Becoming An Instagram Sensation

Whitney Robinson’s Instagram Image by Instagram

Instagram’s most unlikely new star isn’t a twerking pop star or talking cat.

She’s a 79-year-old Holocaust survivor in Great Neck, NY, whose Shabbat-dinner cooking videos have become a viral sensation with a celebrity following.

Miriam Karimzadeh has had some help, as she’d be the first to admit. Her son, Marc Karimzadeh, is the dapper, high-profile editorial and communications director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. His husband, Whitney Robinson, is the irrepressible editor-in-chief of Elle Decor and the host of Bravo’s hit “Best Room Wins”.

The globetrotting couple – whose social set includes first-name-basis luminaries like Diane (von Furstenberg), Donna (Karan), and assorted royalty – join Miriam for shabbat dinner whenever they’re all in New York.

It was Robinson who started posting videos of his mother-in-law’s cooking – like her spin on tadig, the Persian rice dish with an irresistibly crusty bottom.

“People have gone bananas,” said Robinson, who grew up “more Woody Allen Jewish” on Philadelphia’s tony Main Line. “Everyone’s asking to come over for dinner — fashion people, celebrities, people I work with at Hearst.”

While Robinson and Karimzadeh knew Miriam’s cooking was special, “we did not expect this kind of response,” Karimzadeh said. “My mom is my mom. I never thought of her as an Instagram sensation. Though as her only son and the baby of the family, I did always think she had star potential.”

And no one’s more taken aback than the center of attention herself. “I didn’t even know they were posting,” Miriam Karimzadeh said. “I don’t do anything on social media. So yes, I was surprised. But I’m proud that people like the food.” The biggest hit online has been her very personal spin on tadig. “I make it with potatoes, egg, rice, and saffron, so it comes out more like a cake,” she said. “And it looks good.” Traditional gefilte fish and chopped liver are also in her repertoire.

To understand what makes Miriam Karimzadeh’s food so distinctive, it helps to know her story.

Born in Kovno, Lithuania in 1940, Karimzadeh and her family were sent to the notorious Kovno ghetto in 1941. After her grandparents and relatives were murdered by the Nazis, Karimzadeh’s mother managed to get her into hiding. Her “hidden” family ended up in Germany, where Karimzadeh reunited with her mother in 1946.

In 1960, she moved to Hamburg, in what was then West Germany; Kiel, where she had settled in East Germany, had “no Jewish life,” she said. A year later, she met her husband, a member of Hamburg’s then-thriving Persian-Jewish community. They had three children. “That community took me in,” she said. “I learned the language. And I learned to cook Persian food more than Ashkenazi food.”

The match was unusual for the time, Robinson explained. “Marc’s mother was working at a Jewish organization, and his father was looking for a Jewish bride. At the time, very few Persian men who married outside of the community. His mother worked hard to ingratiate herself. She learned Farsi. She learned to cook from her Persian neighbors and friends. Even back then, before Marc was born, they had Shabbat dinner weekly. That’s where the tradition started.”

One of the unintended results was a unique style of cooking that melds the precision and softer flavors of German cooking with spikier Persian cuisine.

“Her take on Persian cuisine has a European inflection,” Karimzadeh said. “Her spices are more subtle. Everything’s more tailored to Western palates. It’s just how she likes her food. I loved her food growing up. She makes a stew with eggplant that’s extremely delicious, and sometimes covers the tadig with the stew. It has a great flavor profile. I’m not sure she’s aware of this, but you feel the sense of love she has for tradition.”

Robinson agreed. “Persian food has an almost Indian flavor. But because she’s German, the flavors get tempered. Marc’s mother puts potatoes in her tadig, for example. But she can also do a roast chicken with onions and a German apple cake. Her cooking tastes like no other Persian cooking we’ve had.”

The shabbat dinners continued when the Karimzadehs moved to suburban New York in 2001. Robinson joined the family almost immediately when he and Karimzadeh became a couple 13 years ago. “We have always had guests, even back in Germany when my late husband would bring people from outside the family,” Miriam Karimzadeh said. “It’s good for me.”

The dinners “are integral in my life. It’s the yang to the yin,” Robinson said. “It’s our family time, and it’s who Marc and I really are at the core. On our first date, we both put our phones on the table. They rang at the same time. Both screens said ‘Mom’. That’s when we knew.”

And while the whirlwind around the shabbat dinners continues to grow – Robinson and Karimzadeh said a cookbook may be in the works – Miriam Karimzadeh remains unfazed. “Would I get nervous if celebrities came? Not at all,” she said. “I like guests.”

Her son agreed. “My mother’s the least star-struck person in the world,” Karimzadeh said. “She’s no-nonsense. That’s why people love her.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO